25 October 1817: Visit to James Rice & Some Key Questions

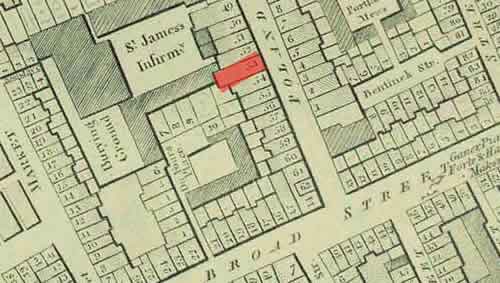

50 Poland Street, London

Where Keats’s acquaintance James Rice, Jr. (1972-1832) lives. Rice is trained in the law, and later Keats’s younger sister, Fanny, will employ him as her lawyer. He is evidently very well read. Keats becomes acquainted with Rice via another friend, the writer and sometimes poet John Hamilton Reynolds, who is later partnered by Rice (who pays for Reynold’s training) in the law practice Rice takes over from his father. Rice seems to have later turned over the whole practice to Reynolds, though Reynolds made little of it.

On this evening, Keats (just about to turn 22) calls on Rice and his family after being ill for the previous couple of weeks and confined to Wentworth place (Keats has taken some mercury). Rice himself has just been ill (he suffers continually from some kind of illness (possibly consumption), which may have been the cause of his death at age forty. Keats’s younger brother, Tom, is also seriously unwell at this point, and there are fairly obvious signs of consumption. This worries Keats enough that he considers sending Tom to a warmer climate—to Lisbon—and to perhaps accompany him. In just a few years, Keats will himself be in Tom’s position, and looking to a warmer climate in an effort to remedy his own lingering but unstoppable consumption. Keats returns the favor and has Rice over on the 27th.

Keats greatly enjoys Rice’s company: he finds him

unconditionally witty and wise, entirely sensible, and admirably buoyant, even with

his

wavering health. As Keats writes to another friend, he hopes can spend every Saturday

with

Rice until we know not when

(letter to Benjamin

Bailey, 28-30 Oct 1817).

Significantly, in this letter to Bailey, in

which he discusses Wordsworth’s poem Gipsies as criticized by literary critic and essayist William Hazlitt, he judges Wordsworth’s poem as

lacking depth, being overly intellectual, written from a position of comfort, and

not a

search after Truth.

This tells us something significant about the evolving poetical

position (or disposition) Keats is growing into in order to progress, as well his

view of two

Wordsworth’s—one early and one late, one feeling deeply and one hardly feeling—that

Keats

attempts to deal with. This is underlined by the political Wordsworth of late, whose

political

affiliations conflict with much of Keats’s circle.

Keats is stuck between indolence and his desire to complete his long, testing, and largely lackluster poem Endymion within a month or so. Indolence, though, is a disposition that interests Keats, and he moves between embracing it as a poetic state to explore and rejecting it in favor of very deliberate application of his creative energies. Keats is very capable of both worrying and not worrying about worrying—of operating between states of passive receptivity and engaged participation; in fact, this may be key to understanding one aspect of Keats’s developing poetics and his complex poetic progress. How can he write poetry that captures both states, as both conflicted and conflated—and without judgment? His best poetry, mainly that of 1819, manages to do so. How can he enter a subject without subjectively wallowing in it? How will he balance intensity and disinterestedness? How can he commingle thinking and sensation? How will he poetically embrace knowing and not knowing? The solution comes by answering these questions with poetry itself.

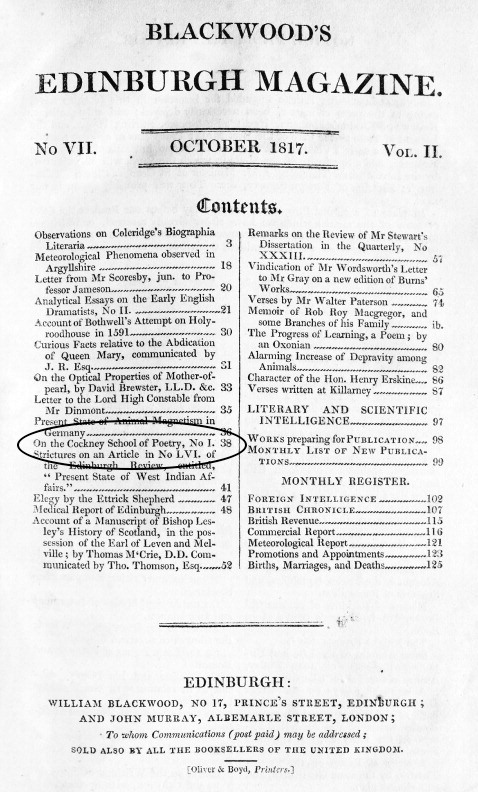

October 1817 is also noteworthy in that the first of a series of vilifying essays

about Leigh Hunt appears in Blackwood’s Edinburgh

Magazine (no. 7, vol. 2, p.38), and it won’t be long before their delightfully damning

aim captures Keats as Hunt’s hapless minion. The term is now set for a particular

part of the

Regency cultural wars: Hunt, Keats, and their circle are nominated as The Cockney School of

Poetry.