Early October 1817: Haydon’s Influence & the Problem of Literary Men

22 Lisson Grove North (now No. 1 Rossmore Road), London

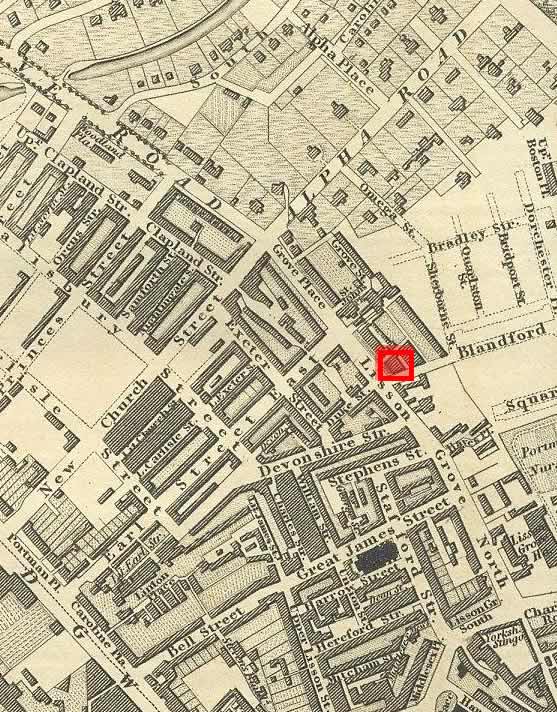

22 Lisson Grove North: where the established historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon moves, 27 September, after having his studio at Great Marlborough Street, London.

Haydon becomes Keats’s friend a year earlier, in October 1816, when the life-changing expansion of Keats’s London connections takes place through celebrity journalist, poet, and critic Leigh Hunt, co-publisher of the independent (and openly progressive) journal, The Examiner, and the venue in which Keats is first published.

Haydon is central to Keats’s social and

intellectual expansion.* Haydon greatly respects the young, unknown Keats—in fact,

he feels

they are bonded, kindred spirits. Earlier in the year, on 17 March, Haydon signs off

a letter

to Keats with let our hearts be buried in each other.

Initially, at least, Keats is

hugely impressed by the older (by almost 10 years) and well-known Haydon, and Haydon

returns

much respect while offering incredibly strong belief in Keats’s calling as a poet.

In

anticipation of meeting him, Keats’s refers to him as this glorious Haydon

(letters, 31

Oct 1816). For his part, as Haydon recalls in his diaries, what amazes him about Keats

is his

prematurity of intellectual and poetic power

(Haydon’s Diaries and Journals, [1853, 1950] p. 295). Haydon in fact views Keats in the same

way he sees himself: as the sensitive, unacknowledged genius, though barely beneath

Haydon’s

character lurks an off-putting combination of aggressive stubbornness and aggrandizement,

which came across to some as simply vanity. But he is much more complex than that,

as his

diaries reveal.

No doubt Haydon’s theories and opinions about

art influence Keats, given, first, Haydon’s intense commitment to art and its greater

social,

aesthetic, and historical importance; and second, how much time Keats and Haydon spent

together during, arguably, Keats’s most formative period. Before meeting Keats, we

find

dispersed in Haydon’s earlier journals that some of his notions about art’s importance

and its

qualities partly square with Keats’s developing poetics, and, again, these ideas almost

certainly spilled over into the large number of conversations Haydon had with Keats.

For

example, dispersed throughout his journals, Haydon is clearly passionate about the

idea and

privileging importance of beauty; and at one point, in the context of describing an

appropriate response to the Elgin Marbles, Haydon writes about being alive to their beauty

and truth

(in his journal entry of 23 Feb 1816). The anticipatory proximity to Keats’s

remarkably memorable phrasing at the end of his own homage to Greek art in Ode on a Grecian

Urn—Beauty is truth, truth beauty

—should not be lost on us. This of course

reminds us of the fact that it is Haydon who takes Keats to see the Elgin Marbles earlier in the year (early March), and it is Haydon who, before this,

publicly and passionately expresses how the Marbles represent a supreme expression

of ideal

beauty. Again, some of this thinking no doubt rubbed off on young Keats.

Haydon includes Keats in his large heroic

painting, Christ’s Triumphant Entry into Jerusalem, a canvas

that takes a few years to complete—a few years too many, in fact: bad eyesight and

troubled

striving for impossible perfection handicap him, since he truly believed in his own

and the

painting’s greatness. As suggested, Haydon overestimates his own self-proclaimed genius,

and

flaws in technique and composition are not difficult to see (Haydon’s complex explanation

and

aggrandizing assessment of the painting are best expressed in his 6 October 1831 letter

to a

certain Col Wild

). Haydon also does not manage his own career and affairs very well,

and money issues will later come between Keats and Haydon (Haydon in June 1821 is

arrested for

his debts and jailed two years later). Too often Haydon is quarrelsome and defensive,

both in

his professional and personal encounters—his tragic end is tied to his compounded

difficulties

and personality. He fully believed that one role he had (or was entitled to) was to

save

British art and to raise it to new heights.

Now, in October 1817, a year after Keats falls in with this London network, he has

come to

know some of these persons better, and his wide-eyed enthusiasm is tempered. To Benjamin Bailey, his scholarly friend at Oxford (and

with whom he stays most of September), Keats writes that he is disgusted

by the

pettiness between literary men,

and particularly Haydon and Hunt, who find themselves

jealous Neighbours

at this time, talking behind each others’ backs (8 Oct). Keats is

clearly disenchanted with many aspects of Hunt, who still sees himself as mentor to

Keats, and

who, Keats finds out, makes somewhat condescending comments about the very long poem

Keats is

currently writing and struggling a little with, Endymion;

Haydon warns Keats not to show Hunt his work on the poem, given that Hunt might highhandedly

condemn it, and thereby upset Keats (8 Oct).

In the history of his relationship with Hunt,

Keats finds him likable enough, and he very much respects Hunt’s journalistic and

independent

edge, but the charge of egotism

that begins in May 1817 continues, and perhaps peaks in

an outburst in a letter Keats writes to his brother, George, and wife,Georgiana, at the end of the year: in reality he [Hunt] is vain,

egotistical and disgusting in matters of tastes and morals

(17 Dec). That’s pretty

direct. But perhaps most importantly, especially in terms of Keats’s developing idea

of

beauty’s unassailable, enduring truth, is how Hunt can put his own intellectual egotism

above

a beautiful work itself; thus, as Keats notes, making fine things petty and beautiful

things hateful . . . many a glorious thing when associated with him [Hunt] becomes

a

nothing

(17 Dec 1818). This, for Keats, is almost a kind of heresy. A higher principle

of beauty sustains Keats, and this principle exists beyond opinions, ego, and fashion.

At this point in his poetic progress, independence of direction begins to feature

more

frequently in Keats’s thinking. It bothers him to be seen as Hunt’s pupil (letters, 8 Oct), and Haydon does warn Keats away from Hunt’s sway—Haydon disparagingly

refers to it as the Examiner clique

in his autobiography— as does another good friend,

John Hamilton Reynolds. The low public point

of Keats’s poetic pairing with Hunt is to come: in two devastating reviews, over about

a

month-long period in September 1818 in Blackwood’s Edinburgh

Magazine and The Quarterly Review, Keats is

denigrated as being nothing more than Hunt’s defective, pretentious apprentice and

disciple.

Keats will waver in his attitude about the reviews: at moments he is infuriated; and

at times

he rises above the clever, cutting attacks, realizing they are motivated more by politics

than

by poetical principles. Truth be known: those negative reviews are largely correct

in what

they point to as the more flimsy and ineffectual qualities of Keats’s early poetry.

[*See this flowchart for Haydon’s key placement as a node in Keats’s social network.]