3 September 1817: Benjamin Bailey & Oxford: Endymion’s Doubtful Merit, Profitable Studies, & Correcting the Poison

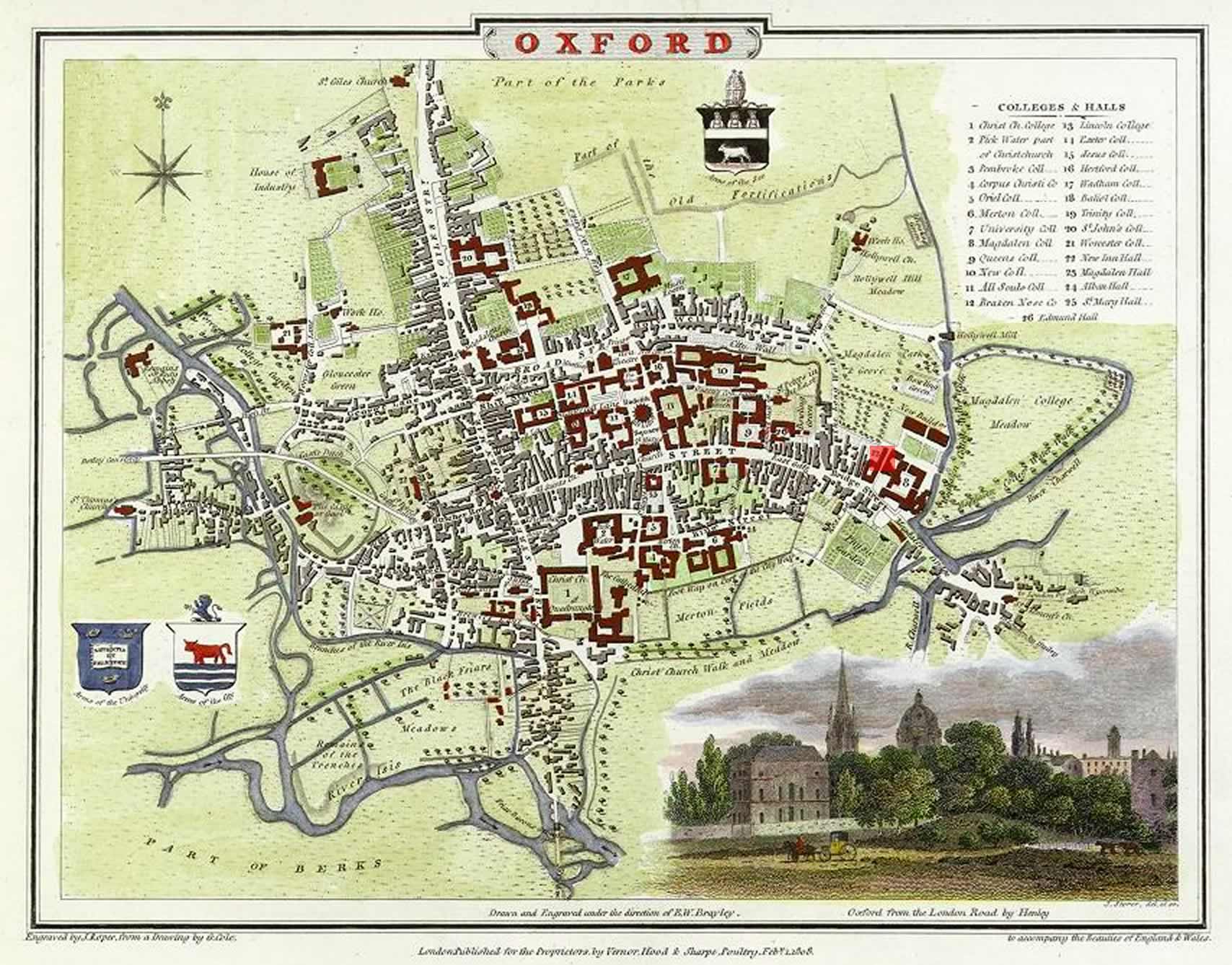

Magdalen Hall, Oxford

Keats (aged 21) stays with his new and now affectionate friend Benjamin Bailey (1791-1853), who, having matriculated from Oxford, is now studying for his holy orders (Anglican) at Oxford. Bailey’s rooms are at Magdalen Hall. Keats meets Bailey sometime in the spring of 1817, almost certainly through Keats’s friend, the writer/poet John Hamilton Reynolds and his sisters.

Keats quickly falls into a pleasing routine of writing while Bailey studies, working steadily on Book III of Endymion, which he

completes a draft of by the end of the month. Together they also enjoy the natural

and

historical ambiance at Oxford, and they explore the vicinity. To Fanny, his sister, Keats writes an enthusiastic letter: This

Oxford I have no doubt is the finest City in the world—it is full of old Gothic buildings

—Spires—towers —Quadrangles—Cloisters—Groves, etc., and is surrounded with more clear

streams than ever I saw together

(10 Sept). He also does a fair amount of boating with

Bailey. But Keats also expresses to Fanny that at moments he is working so hard on

his long

poem that he feels utter incapacity.

He has set himself a daunting task to complete a

very long poem on a relatively narrow narrative.

Bailey greatly respects Keats’s poetic

aspirations and gifts, and Keats finds Bailey so real a fellow,

which is indeed great

praise, though others find the scholarly Bailey a little starchy. Bailey may have

taken a

vaguely tutoring role with Keats; and Keats, eager to expand his thinking, no doubt

soaks up

as much as he can. That Keats comfortably connects with someone as formally erudite

as Bailey

(an Oxford student), as well as someone whose beliefs are clearly theologically driven,

says

something about Keats’s personality and ranging intellectual grasp.

With Bailey, and beside moving steadily on with his poem, Keats also spends time reading, studying, and discussing the likes of William Wordsworth, Milton, Dante, Shakespeare, and William Hazlitt. All are central to Keats’s poetic progress. And given Bailey’s own purposes for being at Oxford, it becomes clear that Keats begins to take scripture and the question of belief more seriously and in a more complex way. In particular, Bailey’s form of theology forces Keats’s thinking about how the imagination acts in, and has relation to, the material world and the operation of understanding and expression.

Bailey also turns some of Keats’s interests to

philosophy, and in particular, to Plato. Again, this exposure encourages Keats to

conceptualize a more complicated poetics and to consideration of the role and nature

of

poetry, though Keats is hardly a tutored Platonist thinker. That the Keats/Bailey

relationship

has some basis in shared philosophical topics is clear in a letter of 13 March 1818

to Bailey,

when Keats writes of mental pursuits,

perception, the mind, and epistemological

categories: things real, things semi-real, and no things. But it is at the intersection

of the

imagination, beauty, and theology where Keats and Bailey intellectually challenge

each other.

Is the imagination just a means to encounter beauty and the world, or is the imagination

an

end-in-itself that allows us to see deeply into all things? Is the imagination a way

to know?

What kind of truth does the imagination render or represent—a form of divine truth,

or a form

of truth in-itself? Keats tends toward the latter. Bailey would have held that imagination

works via analogy; Keats would have held that imagination works via genuine (and therefore

truthful) connection. Bailey, in short, becomes someone Keats can write up

to. And so

more than once we find Keats freely voice various speculations to Bailey, and some

of Keats’s

most important ideas come up in letters to him. [For example, see discussion of Keats’s

crucial letter to Bailey at 28 November 1817.]

By the end of September, to his good friend, the historical painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, Keats confirms progress on Endymion; but he also admits that he is tired of it

and that

he has some doubts about its merit: My Ideas with respect to it I assure you are very

low—and I would write the subject thoroughly again.

He hopes that at least the

Experience

of writing it will, in the future, help him in his poetic progress

(letters, 28 Sept). Already, then, Keats rightfully recognizes the limitations of

a poem like

Endymion in subject, style, and purpose; he also recognizes

that his limitations might be overcome by very deliberate study and by developing

a guiding

poetics: he needs to determine and articulate the critical qualities of great poetry

relative

to his own poetical character—and then write. Given the timing, it is very possible

that, via

discussions with Bailey, Keats comes to see the

relatively inconsequential purpose and shortcomings of Endymion, despite the stamina that Keats exhibits by seeing the self-imposed project—a

test, a trial—through to its end.

In discussing his long apprentice poem with Bailey, Keats quite likely recites passages to him. He may have read to Bailey one

of Endymion’s strongest parts, its opening, with the

undeniably striking first line, A thing of beauty is a joy forever.

An essay Bailey

writes later in the year, A Discourse Inscribed to the Memory of the

Princess Charlotte Augusta (released by Keats’s new publisher, Taylor & Hessey),

opens with a line that strongly echoes Keats’s: When we look upon beauty we cannot think of

death.

Here, too, as mentioned above, we can find how Bailey conceives of the

imagination, relative to Keats.

It just so happens that Bailey knows John Gibson Lockhart, who, in August 1818 in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, anonymously—as Z

—attacks

Keats, Endymion, as well as the Cockney School of Poetry

into which Keats is placed. Z’s roasting of the Cockney School takes place over eight

essays

between October 1817 and July 1825, and is mainly motivated by the desire to completely

batter

Leigh Hunt, who is publicly flagged and

rhetorically flogged as Keats’s model and mentor—this irks Keats. Bailey, with good

intentions, had let Lockhart know about Keats’s medical background, but Lockhart then

uses

this, and publicly ridicules Keats about his decision to be a poet rather than a medical

practitioner: It is a better and a wiser thing to be a starved apothecary than a starved

poet,

Lockhart will cruelly, but wittily, write.

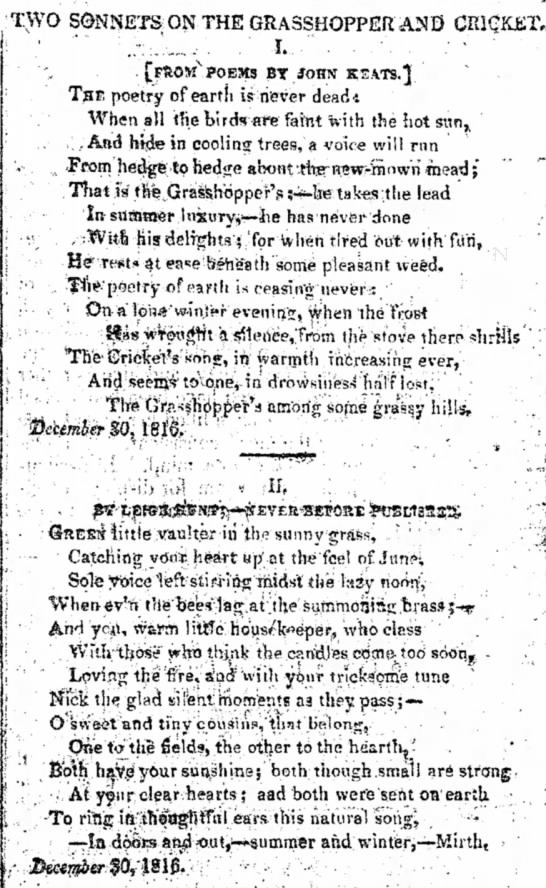

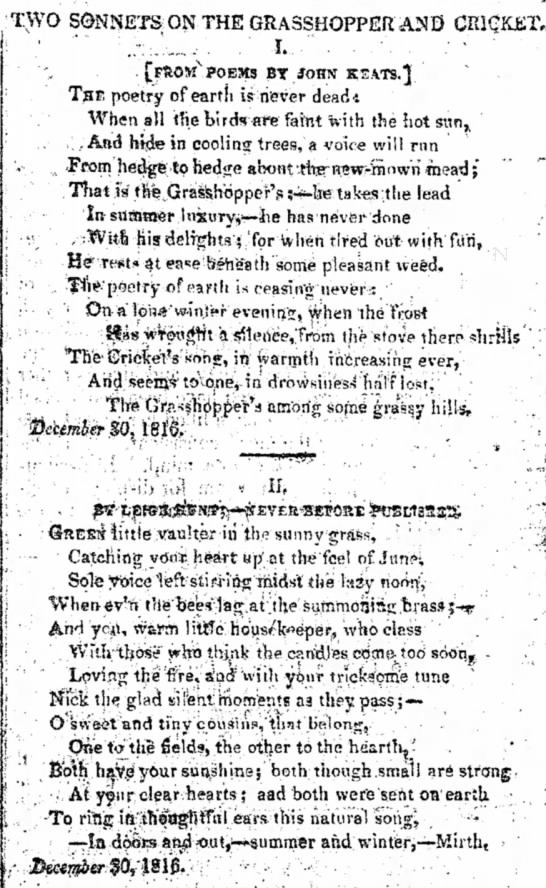

Keats’s sonnet On the Grasshopper and the

Cricket is published in Leigh Hunt’s

The Examiner, 21 September, though first published earlier

in Keats’s Poems collection. The poem (written in December

1816) was composed in a timed competition with Hunt (Hunt also publishes his own poem

at the

same time—see image below). These social moments are not uncommon acts of poetic spontaneity,

and can be contextualized in the spirit of artsy, collegial entertainment; they don’t

usually

result in anything much in the way of literary worth, but they do reveal Keats’s growing

dexterity with the sonnet form. Keats’s sonnet does display potential stylistic ease—and

the

idea that The poetry of earth is never dead

(the first line) is a sentiment Keats

continues to embrace, but phrasing like new-mown mead

signals Huntian poeticisms. Keats

apparently wins this particular poetic challenge.

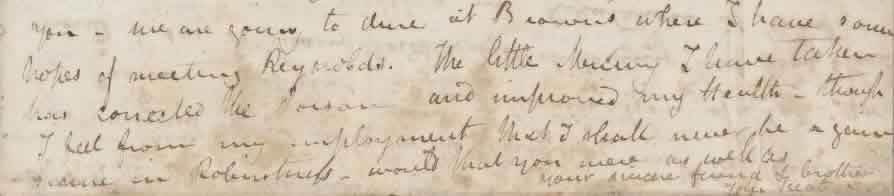

By the time Keats leaves Oxford, health issues begin to trouble him: he writes to

Bailey that The little Mercury I have taken has

corrected the Poison and improved my Health—though I feel from my employment that

I shall

never be again secure in Robustness

(8 Oct). [See this in Keats’s own hand.]

It is possible that the Poison

refers to some form of venereal disease that needs

correction—treatment and healing, that is. Along these lines, we could read into the

last part

of the sentence to suggest that Keats worries he might have lost some of his sexual

drive—Robustness.

But again, it could just mean that Keats feels his loss of energy

might be a lasting condition.

We know Keats uses mercury more than a couple of times—but for what? Mercury, its offshoot calomel (mercurous chloride), and other mercurials were often indiscriminately used as a cure-all for numerous illnesses, ranging from syphilis to dysentery, and including rheumatism, gout, constipation, toothache, swellings, throat problems, and consumption itself; it was used as an antiseptic, a general ointment, and a cosmetic. There were home recipes for mercurial creams that included hogs’ lard and mutton suet. Today we know that continued use of mercury can have serious toxic effects; it can contribute to systemic weakness, particularly in the kidney and liver, as well as oral issues, like excessive salivation. High usage can also, according to some, result in behavioural or mood unevenness.

Perhaps—but only perhaps—mercury plays a minor role as a symptom in Keats’s early passing. However, given Keats’s symptoms in the last year of his life (sweating, fever, physical atrophy, blood-spitting, symptoms moving from the throat to the lungs), and given his full exposure to tuberculosis, the prevalence of the illness at the time, and extensive family history of deaths caused by tuberculosis (mother, uncle, and two brothers), tuberculosis is clearly the full cause of his slow and agonizing death in Rome, February 1821. There is no evidence that Keats took large amounts of mercury, though if he were suffering from venereal disease, large doses were very often prescribed; at the same time, a few physicians promoted the use of small amounts over time, particularly for venereal diseases (at the time, syphilis and gonorrhea were viewed as a single disease). Over Keats’s lifetime, there was some growing concerns about the over-use of mercury, though the fetish for pale skin for women through the Victorian ensured continued use of mercury (not to mention arsenic and lead), and use of mercury pills for various medical problems continued.

Keats is back in Hampstead by 5 October to meet up with his brothers (who have been

holidaying in France), but not until, with Bailey, he visits Stratford-upon-Avon for

two days at

the beginning of October. Like other tourists of the day, and in the spirit of bardolatry,

Keats wants to experience what he can of the Bard of Avon. After all, in Keats’s very

deliberate, studious attempt to become a certain kind of enduring poet—to become,

like

Shakespeare, a chameleon Poet

(letters, 27 Oct. 1818)—understanding Shakespeare to his

depths is crucial in shaping his poetical character and identity, and thus in advancing

his

rapid progress as a poet.