13 July 1817: No Natural Proportion: Hunt Reviews Keats’s Poems & the Vast Idea

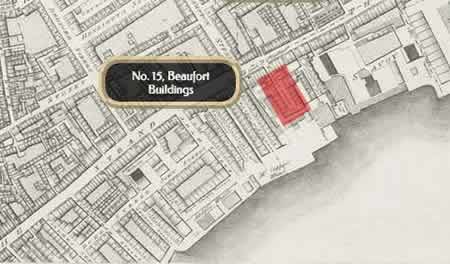

No. 15, Beaufort Buildings, Strand, London

Some time during the first week or two of June 1817, Keats (aged 21) moves back to

Well Walk

in Hampstead. Money troubles continue, and he asks his publisher, Taylor & Hessey,

for a loan of 30 pounds. By some point early in June, Keats likely completes a first

draft of

the first book of his ambitious project poem, Endymion. Keats’s motivation: he sees the

long poem as a guiding test of Invention

undertaken by all great Poets

(Keats

quoting himself in letter written earlier in the year, and copied into a letter of

8 Oct). The

project from the beginning seems so overly deliberate—young Keats out to prove something,

to

himself and to the literary world—that having something truly remarkable emerge is

unlikely,

especially given Keats’s relative poetic immaturity. But we understand the shortcomings,

in

both motivation and execution; thankfully, so does Keats.

No. 15, Beaufort Building: the offices of The Examiner, the

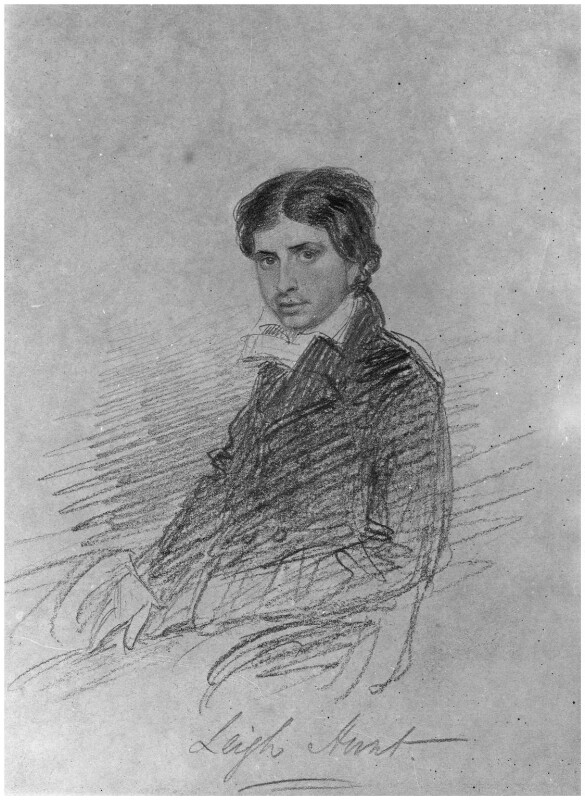

independent journal published by Keats’s good friend and (initially) mentor, Leigh Hunt. (Hunt’s brother, John, also runs the paper, and Hunt’s other brother, Robert, also at times contributes to it.) Keats is

introduced to Hunt back in October 1816—and, understandably, he is absolutely thrilled

at the

prospect of meeting one of his heroes; starry-eyed Keats writes that it will mark

an Era in

my existence

(letters, 9 Oct 1816), and it is. Yet in the last few months of mid-1817,

Hunt’s luster has dulled: in particular, Keats at moments has become put off with

aspects of

Hunt’s egotism, and mainly with Hunt’s delusions about being a great poet.

On this day, the third and final part of Hunt’s review of Keats’s first collection of poetry—Poems, by John Keats—appears in The Examiner. The other two appear 1 June and 6 July, though the first review only mentions Keats in the first paragraph. The gaps in the dates between the first and second installments seem odd, though Hunt simply tells his readers that there were other pressing matters. That Hunt takes so long to get around to writing the first installment is also odd, given that Poems is published in early March. The lag may have been a result of Hunt’s own personal issues (financial, as well as a move from Hampstead—did he misplace the book?), and there is some evidence that Hunt at the last moment did not want the first installment to be published. The final complication is that Poems is in fact dedicated to Hunt, and so the question of patronage—nepotism, in fact—hangs in the air. This point will not be lost upon some reviewing quarters.

The second installment of the review (6 July) explains Keats’s faults,

errors,

and mistakes common to inexperience

—mainly, the indiscriminate

description and poor use of versification. Hunt is

right, though his own verse sometimes is guilty of awkward and off-putting versification.

In

truth, Hunt is a better critic, journalist, and essayist than he is a poet.

The third installment of the review (13 July) applauds the warm and social feelings

in

Keats’s poetry. Hunt concludes that the best poem in the collection, Sleep and Poetry, is a striking

specimen of the restlessness of the young poetic appetite.

Once more, Hunt is largely correct on both accounts: Keats’s early work does

indeed often express or carry the sentiments of cozy sociability that Hunt himself

fully

embraces and promotes. And so Hunt notes that Keats’s early poetry is often about

his desire,

his appetite,

to be a great poet; but the poetry too often exhibits some carelessness

via inexperience—it is without an eye to natural proportion and effect,

Hunt adds.

Given that many of the poems in the collection could, technically, be classified as

juvenilia

(Keats admits as much), this is hardly surprising. Keats at this point is a poet in

the

making.

Hunt has a further connection to his favoured Sleep and Poetry. The poem’s speaker

(too obviously Keats) makes various self-admitted boyish yearnings to some day be

a poet (ten

years will do, he suggests); and then, after repeating that the vast idea before me

(291) is his hope to embrace and participate in the end and aim

(293) of poetry, at the

end of the poem he situates himself in what we know, and what Hunt knows, is Hunt’s

own study,

with all its artsy and eclectic nicknacks, and where Keats used to nap and spend the

night. In

a way, then, Hunt stands behind the inspiration for Sleep and Poetry. No wonder he likes it.

Hunt’s critical observations about Keats’s

collection are generally correct, and his comments may have been in some degree useful

for

Keats, though we also have to imagine a deeply ambivalent response from Keats. If

we piece

together the three installments of Hunt’s review, we get this kind of narrative: Hunt

rightly

confesses he is Keats’s friend, but that their initial connection was made by nothing but

poetry.

Then, by way of analyzing the course and graces of a natural style in English

poetry (with Hunt declaring William

Wordsworth the most advanced contemporary poet in this respect), Hunt comes to

Keats’s poetry, which he suggests inherits and reinvigorates some of these natural

tendencies.

Keats, Hunt writes, deeply possesses a sensitiveness of temperament,

but his passion for beauties

in fact takes him to the faults of inexperience and

non-discrimination in his work—his poetry, suggests Hunt, struggles with the differences

between the need for microscopic detail and general feeling.

Moreover, Hunt adds, Keats

struggles with the more complex relationship between versification and meaning. But

in the

end, Hunt concludes that the beauties of the poetry vastly outnumber the faults.

As mentioned, Keats, then, will have to move beyond these subjects and this style for his poetry to progress. In doing so, he will go far beyond Hunt’s own poetry and poetic abilities, and in a very different direction. But first, Keats must (so to speak) get Endymion out of his system; the second of its four books will be completed this summer.