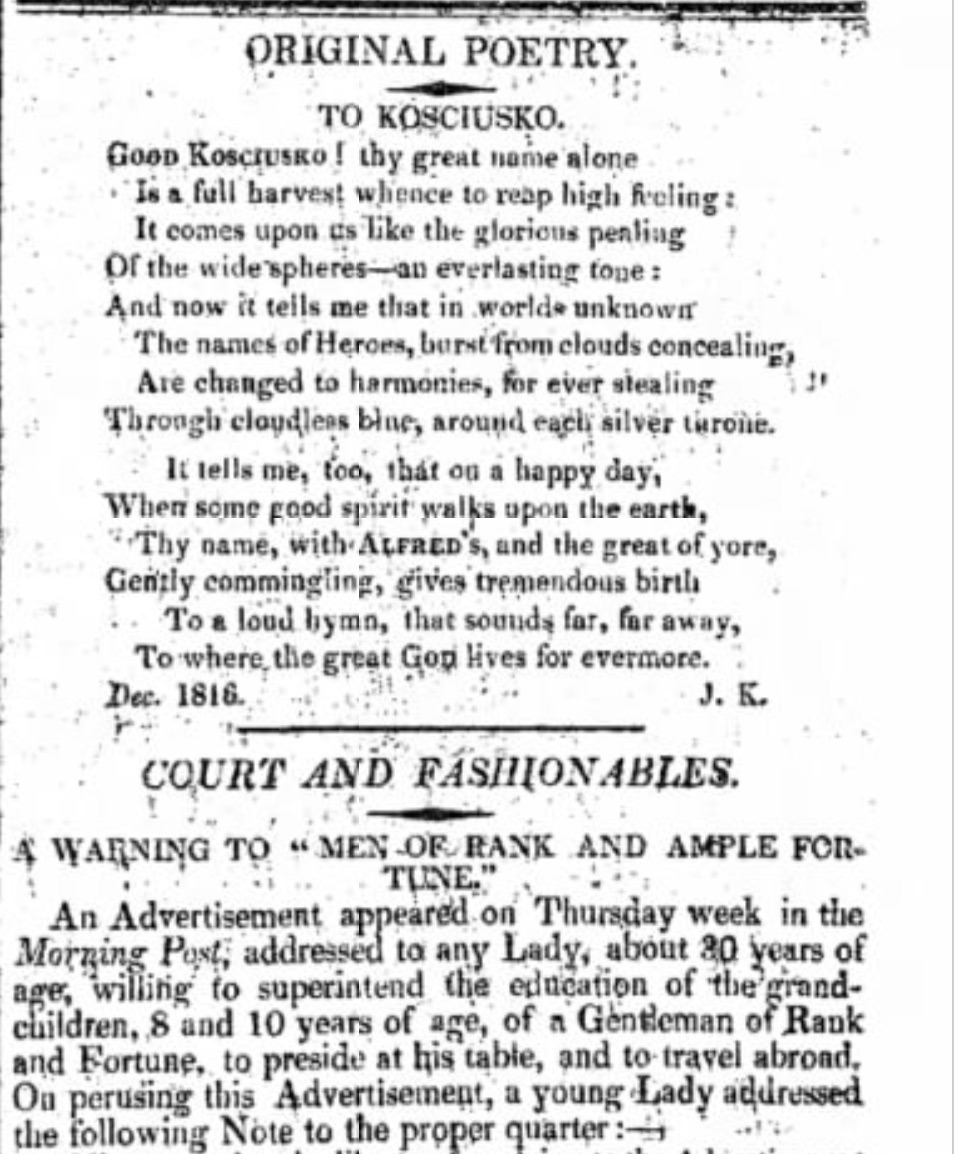

16 February 1817: The Examiner publishes Keats’s To Kosciusko

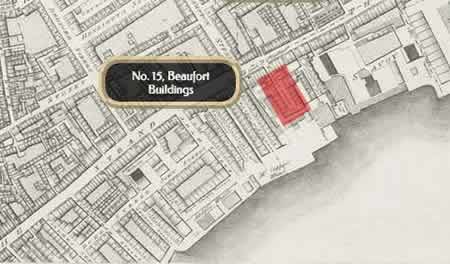

No. 15, Beaufort Buildings, London

On 16 February 1817, Leigh Hunt’s Examiner publishes Keats’s sonnet To Kosciusko, which honors the aging Polish

patriot and freedom fighter. The poem, written in December 1816, attempts to find

a way to

praise Kosciusko, but ideas about the everlasting

and the evermore,

combined

with imagery that moves from harvesting, spheres, clouds, cloudlessness, and thrones,

and that

at once places us in the sky, on the earth, and to where God lives, signal the poem’s

equal

measures of confusion, enthusiasm, and unoriginality. This poem is a little unusual

for Keats:

it overtly waves a certain political stance that puts him onside with Hunt, who is,

unlike

Keats, consistently a political animal—remembering, of course, that Hunt just spent

two years

in jail for libeling the Prince Regent, and that The

Examiner was a champion of issues like freedom of the press, equal representation and

taxing, abolition of slavery, parliamentary reform, and so on. By writing the poem,

Keats

would have mustered some favour with Hunt, and that may have in fact motivated Keats.

There is a bust of Kosciusko in Hunt’s library, where Keats is known to lounge and nap. The library’s décor also appears in Keats’s Sleep and Poetry, which he works on at the end of 1816, and will be the last poem in Keats’s first collection (Poems), to be published in just a matter of weeks. The book will be published by acquaintances Keats makes via Hunt—the Ollier brothers, Charles and James. They will shortly become C. & J. Ollier, Publishers and Booksellers, 3, Welbeck Street, Cavendish Square. Keats will have to come up with funds to pay for the volume’s publication costs, which would not have been unusual, given Keats’s relatively unknown status. The Olliers will get a small commission on sales. Keats will, however, switch publishers for his other two books (1818 and 1820), and part of the reason he might have switched could have been tied to his desire not to pay for publication costs.

Hunt’s Examiner is also the venue for Keats’s first appearance in print, publishing his O Solitude on 5 May 1816. So, too, does it publish other poems by Keats, including On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer (1 December 1816), On the Grasshopper and Cricket (21 September 1817), After dark vapours (23 February 1817), The pleasant tale is like a little copse (16 March 1817), and On Seeing the Elgin Marbles (9 March 1817). Thus Keats’s appearance as a public poet immediately places him within Hunt’s sphere of influence. This is good news and bad news: good, inasmuch has Keats now has an audience for his work, can call himself a published poet, and Hunt importantly connects Keats with a number of persons who will influence, test, and support his poetic directions; and bad, because affiliation with The Examiner and Hunt pigeonholes Keats’s politics and poetics, often privileging the former over the latter. It will not take Keats long to deliberately strive for an independent identity and poetic voice, and to abandon poetry that he thinks will please Hunt.

It is also on this day that, at a dinner party that does not include Keats, Hunt shows some of Keats’s poetry to a fairly impressive audience: William Hazlitt, William Godwin, Percy and Mary Shelley, and Basil Montagu.* Socially, Keats sees quite a bit of the Shelleys in January and February, just after Shelley has, controversially, married Mary Godwin in late December. No doubt Keats has never met anyone quite like Shelley, who, it seems, warns Keats about publishing immature poetry. About three-and-a-half years later, after Shelley invites Keats to Italy in order to help him with serious health issues, the subject later comes up in letters between the two young poets. Keats and Shelley are implicit rivals, which, given their very different backgrounds, appearance, experience, and dispositions, is hardly surprising. Their association with (and through) Hunt does, however, join them—in fact, Hunt does so in a little piece proclaiming them as new and important Young Poets.

Hazlitt, via his writing, lectures, and friendship, will later become a crucial influence on Keats’s poetics.

Earlier in the month, Keats does not take an examination that would have given him membership in the Royal College of Physicians, though he may not have qualified by not attending associated lectures. This confirms Keats’s decision not to enter the medical profession, and equally confirms his decision to become a poet.

* Except for Montagu, this dinner company needs

little introduction, though his life and connections are intriguing. Montagu is the

son of the

4th Earl of Sandwich and his mistress, Martha Ray, popular singer, who is famously

murdered

leaving Covent Garden Theatre, April 1799. Montagu is a barrister and expert on bankruptcy

and

chancery, with interests in copyright and religious emancipation. He is a very good

friend of

both William Wordsworth (who ends up loaning

Montagu a fair amount of money) and Samuel Taylor

Coleridge, as well as William Godwin

(Montagu is present at the death of Godwin’s wife, Mary Wollstonecraft, giving birth

a

daughter, best known to us as Mary Shelley).

After the death of Montagu’s third wife, Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy take care

of

Montagu’s son—Basil—for a period of time at Alfoxden, and Basil, as Edward,

ends up in

a few famous poems. In 1810, Montagu tells Coleridge that Wordsworth considered him a drunk and a nuisance, thus putting a

wedge between the two poets for a few years.