25 July 1816: Keats Passes Medical Exams

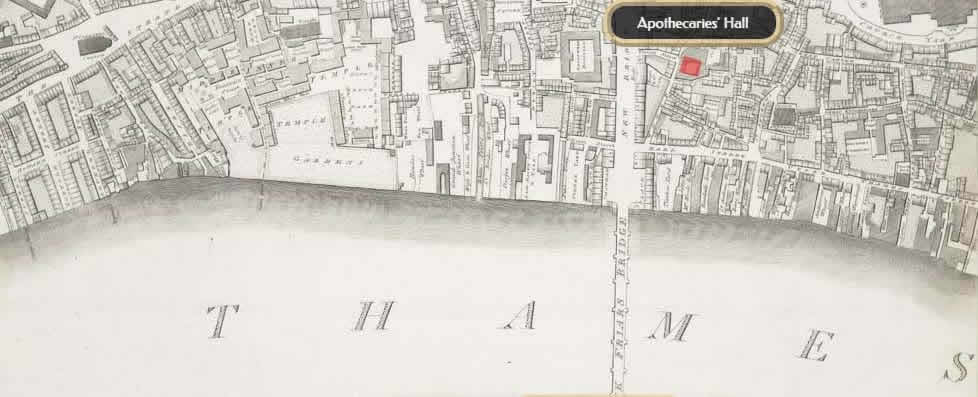

Apothecaries’ Hall, Black Friars Lane, London

Thursay, 25 July 1816: Twenty-year-old Keats passes his medical exams at Apothecaries’

Hall

to qualify as an apothecary. It is neither an easy qualification nor a rubber-stamping

examining process, and only a minority of the students were permitted to sit the exam.

The

exercise of regulated qualification was intended, as the July 1815 Act states, for better

regulating the Practice of Apothecary in England and Wales.

The premise for the Act,

then, was about building credibility and consistency in the medical practices of the

age.

There were simply too many bogus claimers, shady practitioners, and miracle cures

clamouring

to separate the downhearted, suffering, or desperate from their money. Newspapers,

magazines,

and pamphlets were full of products and practices in the rapidly expanding market

place of

health restoration. Certification of those genuinely trained was seen to be imperative

for the

medical profession.

By December, Keats’s name appears as certified in the London Medical Repository. Against his family trustee’s strong advice (Richard Abbey), Keats begins to nix the possibility of a medical profession. The pull of poetry is too strong, and his appearance in Leigh Hunt’s Examiner in May 1816 with his first published poem—O Solitude—likely seals the poetic deal for Keats, though he will continue a little further with his medical training into 1817.

Interestingly, in September 1819, and just at the period he has hit his stride as

an

exceptional poet, and while thinking of a career to maintain himself (perhaps as a

journalist

or reviewer), he writes to very close friend Charles Brown, In no

period of my life have I acted with any self will, but in throwing up the

apothecary-profession

(22 September).

1816 marks the year that, despite his medical qualification, his writing begins to take over his energies, and by the end of the year he is fully thrown into a mainly liberal-progressive literary network—channeled mainly through Leigh Hunt—that further propels his poetic aspirations and directions.* Though his literary path seems set, Keats seems to have remained in the position of surgical dresser until very early March 1817. A few years later, when family funds (based mainly on credit) begin to dry up, and when his poetical career seems not to result in any pecuniary gain, he will in passing vaguely entertain returning to a medical career. [For more on Keats’s medical training, see 15 October 1815.]

By the end year, Keats will have composed all the poetry that goes into his first collection, Poems, by John Keats, published (on commission) March 1817 by C. & J. Ollier. The volume will contain thirty-one poems, including seventeen sonnets. It will be dedicated to Hunt, and a quotation from Spenser will appear on the title page. In fact, these two figures—Hunt and Spencer—are highly influential in this first phase of Keats’s poetic career. And both are conspicuously, and intentionally, for the most part left behind as Keats (spurred by a fully developed poetics) finds a stronger, more original poetic voice through late 1818 into 1819. That is, though Spenserian romance and the prettifications of Huntian suburban poetry are largely jettisoned, they linger here and there in wording or phrases in a some of Keats’s best work; in fact, Keats’s very last significant poem, The Jealousies, marks a light-spirited and mischievous return to aspects of Spenser—perhaps later he becomes master of Spenser’s poetic spirit, rather than being mastered by it. There is the fact, then, that Keats’s first and last known poems—the 1814 Imitation of Spenser and late 1819 The Jealousies—variously embody the spirit of Spenser. But it is in what takes place in between, in grappling with the likes of Wordsworth, Milton, and Shakespeare, we most clearly see Keats’s remarkable poetical advancement.

[*See here for a graphing of Keats’s social network.]