5 May 1816: To Solitude: Keats’s First Published Poem, Leigh Hunt’s Liberal Spirit of Thinking, The Examiner, & the Possibilities of a Literary Life

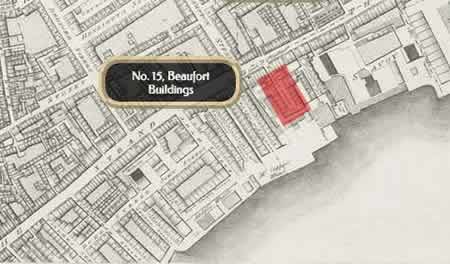

No. 15, Beaufort Buildings, London

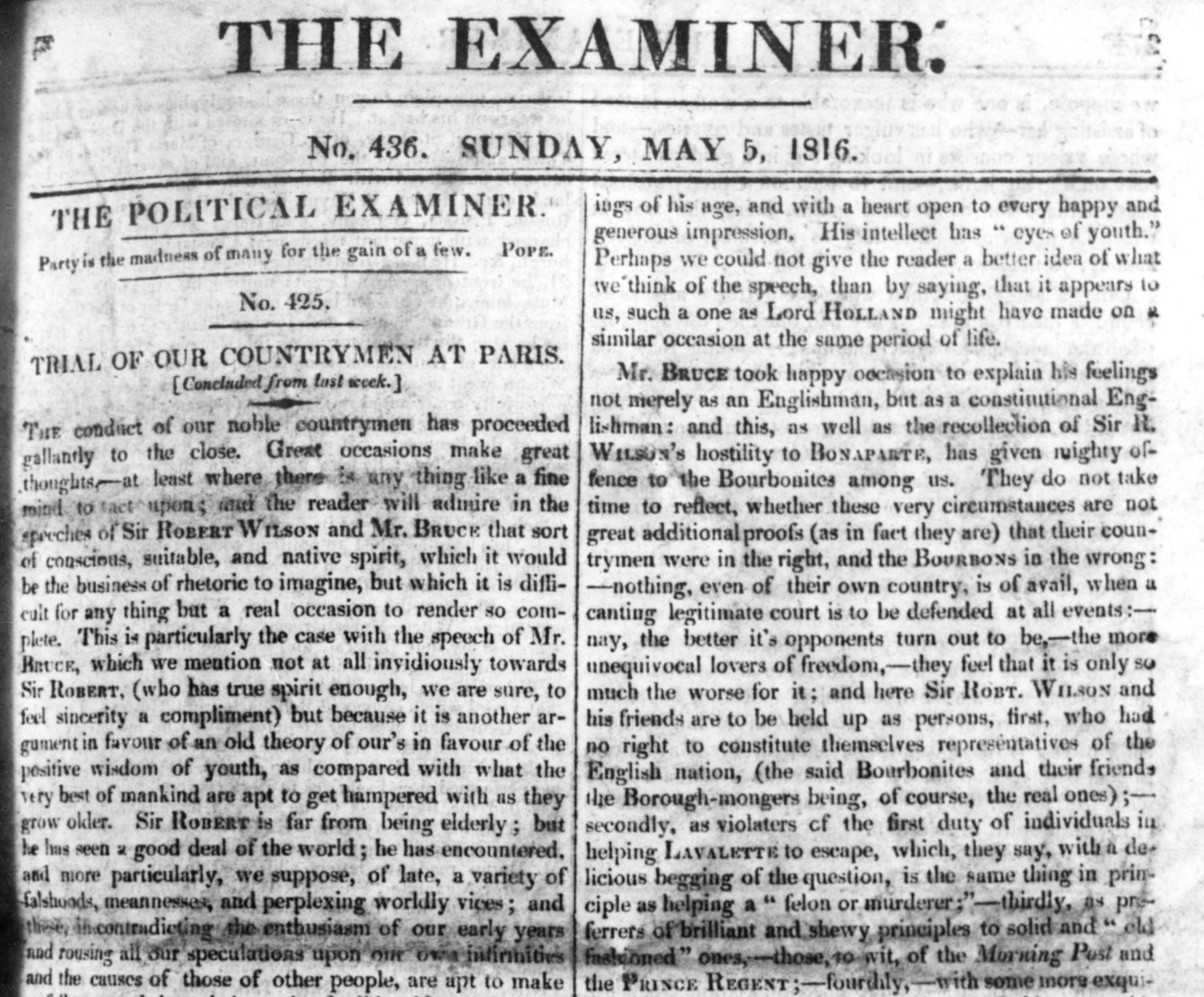

Where the journal The Examiner is published. The Examiner—a strongly independent, reformist paper—is the

venue for Keats’s first published poem, the sonnet To Solitude!, 5 May 1816, as well an important

short piece by its co-publisher and editor, Leigh

Hunt (1 December 1816), which singles out Keats, Percy Shelley, and John

Hamilton Reynolds as young poets of a new school,

one that emphasizes love of

nature and that appeals to thinking over talking; the added promise of these poets,

Hunt

claims, is an understanding of human nature. That Keats’s first publication is in

Hunt’s paper

represents quite an accomplishment, given the already-established poetic company his

poem now

(and suddenly) joins. The Examiner is, both culturally and

politically, front and centre in Regency England debates over tastes, style, and ideology.

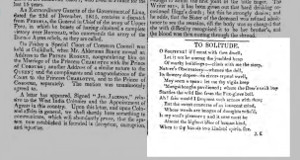

Keats’s To Solitude is

faintly accomplished, though, with its turning to flowery slopes,

leaping deer, and

crystal river, it invokes the fairly common trope of privileging the living scenes

of nature

over the dismal city. One problem in the poem is the vaguely confusing circumstance

that the

speaker’s solitude is sweeter, more pleasurable, and blissful when kindred spirits

can,

in Nature,

partake in sweet converse.

The appeal to nature and solitude also

owes something to Wordsworthian sentiment. The exact composition date of the poem

is not

clear, though it could have been as early as October or November, 1815. Given that

Keats makes

a similar appeals to nature’s restorative effect in sonnets written in the summer

of 1816

(To one who has

been long in city pent and Oh! how I love, on a fair summer’s

eve), dating for To

Solitude could also be spring 1816—that is, not too long before it is

published.

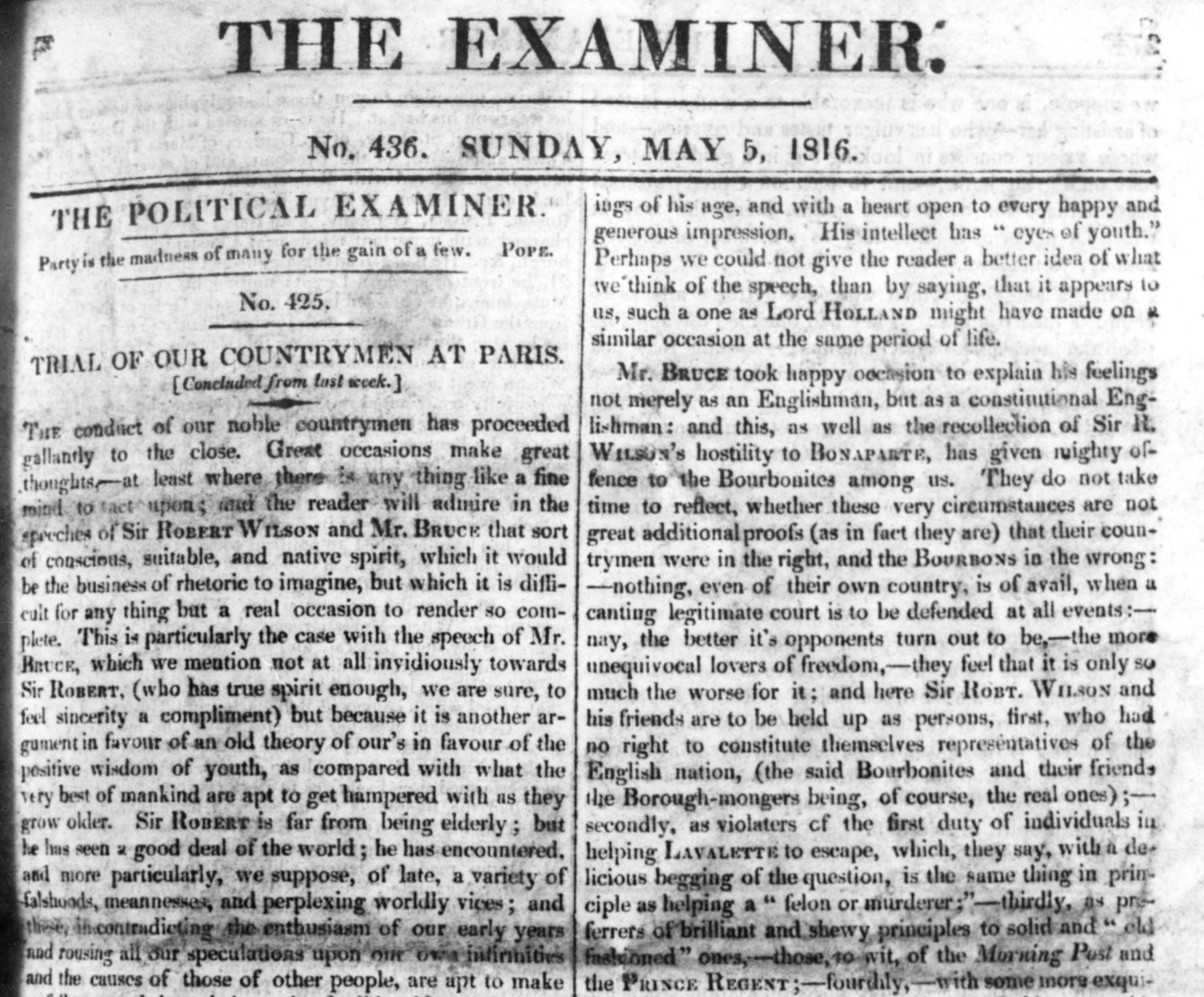

The Examiner—Hunt with his older brother, John, are

co-proprietors of the paper—first appears 3 January 1808 as a 16-page weekly that,

class-wise,

mustered a readership generally ranging from middling to highbrow, with a distinctly

progressive take on most issues. Leigh seems to handle most of the writing and editorial

duties, while John mainly oversees the paper’s printing; a further brother, Robert,

also did

some minor work, including sometimes reviewing (Robert is most famous for attacks

on William

Blake, calling him an unfortunate lunatic

with a distempered brain

; Blake for

his part thought the writers of The Examiner were a bunch of

villainous hacks).

Party is the madness of many for the gain of a few. Pope.Click to enlarge.

At its height, circulation is of The Examiner is about

8,000. The paper’s free-spirited journalism will, in 1813, lead to Hunt (as well as

his two

brothers) being convicted for libelling the Prince Regent. While in jail, Hunt famously

turns

his rooms into artsy quarters where he meets with many of the age’s most prominent

figures, in

a sense forming a kind of jailhouse parlor-coterie. Hunt, writing in his journal while

in

jail, provides the best description of his journalistic values: he writes he is devoted

to

the very general politics, and principally to the ethical part of them, to the diffusion

of

a liberal spirit of thinking, and to the very broadest view of characters and events,

always

referring them to the standard of human nature and common sense

(16 March 1813); we

cannot therefore speak about Hunt without associating him with liberty and reform;

neither can

we ignore his profound understanding of rhetoric, and that words are weapons. Yet

Hunt, to his

credit, remains unsystematic in his thinking. Keats would have been aware of all of

this, and

Hunt becomes a kind of martyr and model for the young Keats—a voice of cultured independence,

coloured by the contemporary political scene, but not rigidly ruled by partisanship.

But

mainly, it is the liberal spirit of thinking

that attracts Keats—and this impulse

travels far back for Keats, where, even at the school he attends as a lad (Enfield Academy),

free-thinking is the desired learning outcome.

Hunt becomes a close friend of and literary influence on Keats by the end of the year. Crucially, Hunt introduces Keats into a wide-range of London’s cultural intelligentsia,* while also unconditionally encouraging Keats’s decision to become a poet. Hunt fashions himself in the role of mentor to Keats, and Keats will in fact be publicly labelled as Hunt’s student, if not his literary lackey. [For more on Keats branded as Hunt’s student, see May 1820.]

But in order to develop into a great poet, Keats consciously comes to compose verses

that

differ from Hunt’s poetry of fancy,

where

ideas of entertainment and sociability are central, which in some ways opposes the

poetry of

imagination. In truth, Hunt’s journalism and criticism, as well as his instincts about

and

ability to connect with smart, interesting people, are superior to his poetic talents.

Yet it

is this large and at times collaborative group around Hunt (which is mainly a literary

community), and via publications like The Examiner, The Indicator,

The Round Table, The Reflector, and The Liberal,

that supports and bolsters Keats’s poetic aspirations.

Significantly, then, young Keats comes to see the very possibility of a literary life within the cultural energies of this large, diverse, and impressive grouping. Though Keats clearly and self-consciously will come to fashion a kind of poetics and then poetry that sees him beyond mere Regency cultural contexts, we nonetheless still recognize something of his Cockney beginnings in his mature Keatsian voice.

*Jeffrey N. Cox includes the following in the Hunt/Examiner circle, what can be

called a second generation of Romantics: Elizabeth Kent, Keats, Percy Shelley, Mary

Shelley,

Lord Byron, Benjamin Robert Haydon, John Hamilton Reynolds, Charles Armitage Brown,

the Ollier

brothers, Horace and James Smith, Charles Cowden Clarke and his wife Mary Novello,

Bryan

Waller Procter (Barry Cornwall

), Vincent Novello and his wife, Thomas Alsager, Thomas

Barnes, Thomas Love Peacock, William Hazlitt, Edward Holmes, William Godwin, Thomas

Richards,

the Gattie brothers, Charles Wells, Charles Dilke, P. G. Patmore, John Scott, Walter

Coulson,

Charles Lamb, Barron Field, Joseph Severn, Douglas Jerrold, Thomas Noon Talfourd,

and

Cornelius Webb. (Based on Cox’s Poetry and Politics in the Cockney

School, 1998.) [*See this flowchart for Keats’s placement as a node in

part of this circle.]