3 February 1820: Consumption: That Drop of Blood

; I Wish I had a little

Hope

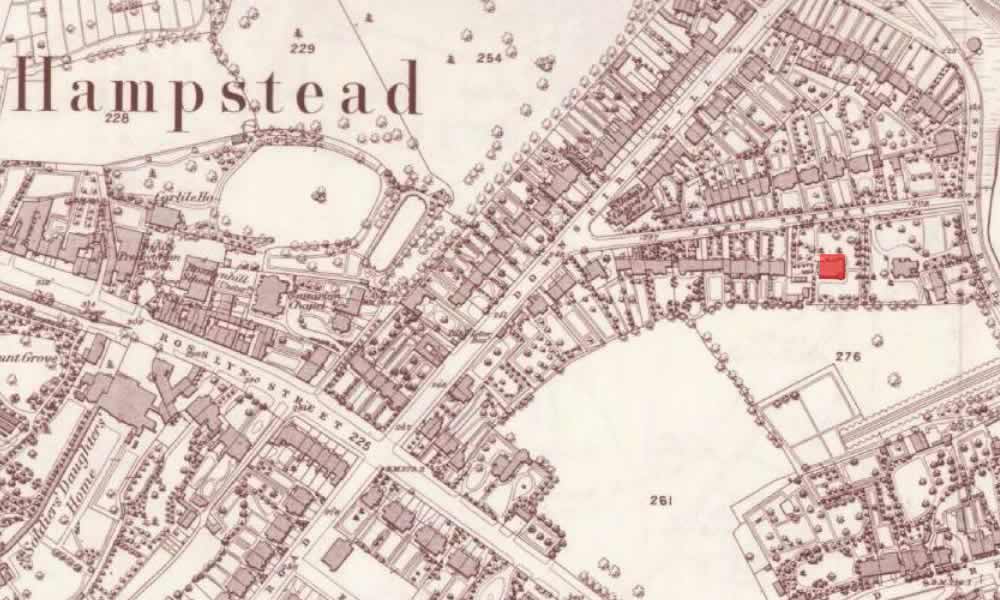

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Late evening, 3 February 1820. Freezing weather has gripped England. After travelling in an open carriage from London to Hampstead with the bitter wind coming at him (and without his new heavy coat), Keats arrives home both chilled and fevered. Upon immediately getting into bed, Keats coughs a little blood onto his pillow. He asks for candle light. His very close friend and roommate at Wentworth Place, Charles Brown, recalls what Keats says, though some of Keats’s actual wording might be slightly magnified by Brown:

I know the colour of that blood;—it is arterial blood;—I cannot be deceived by that

colour;—that drop of blood is my death-warrant;—I must die.

Brown runs for surgeon, who decides to bleed Keats. He’s then placed on a starvation diet and told to rest. This is not good.

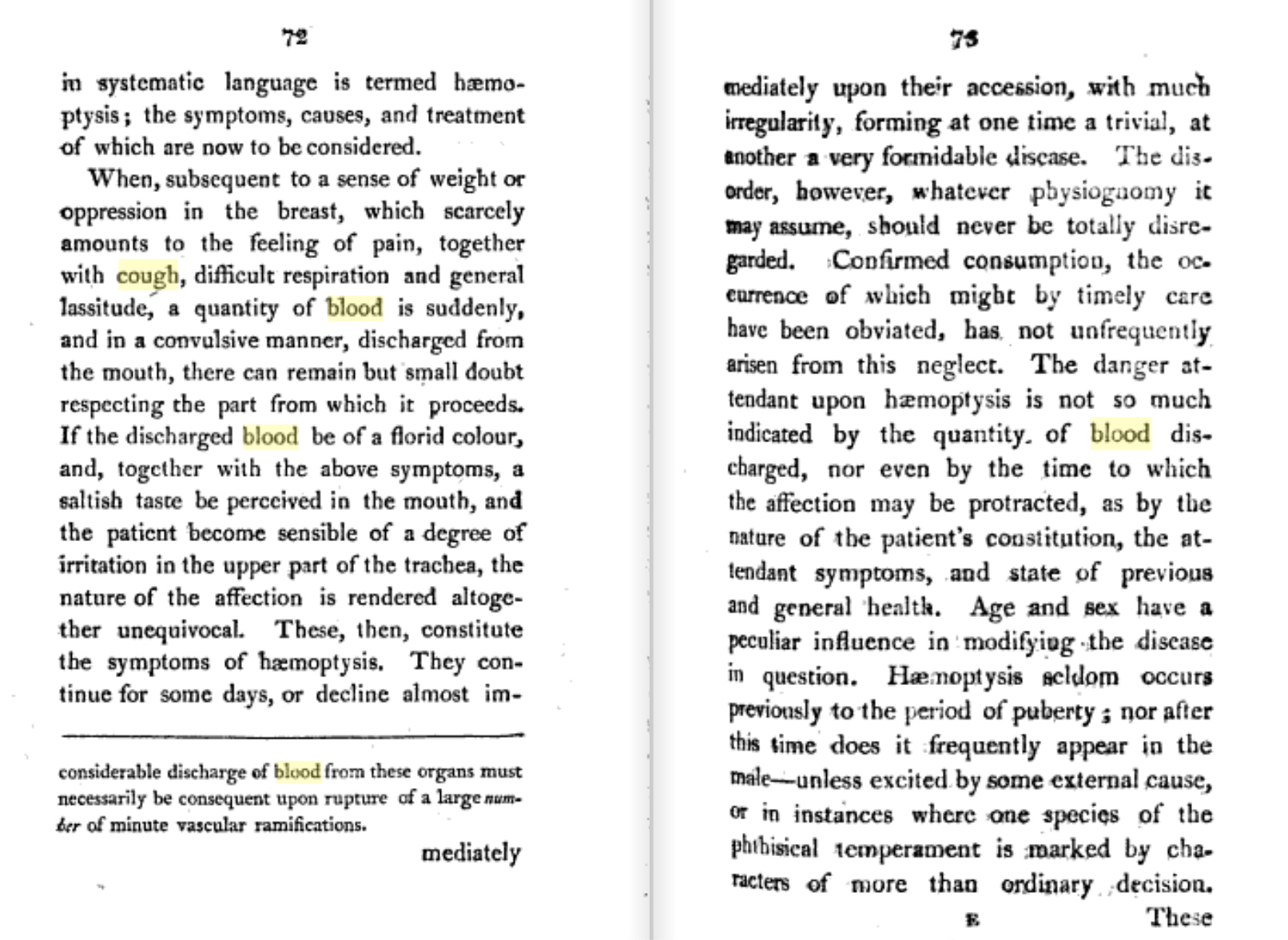

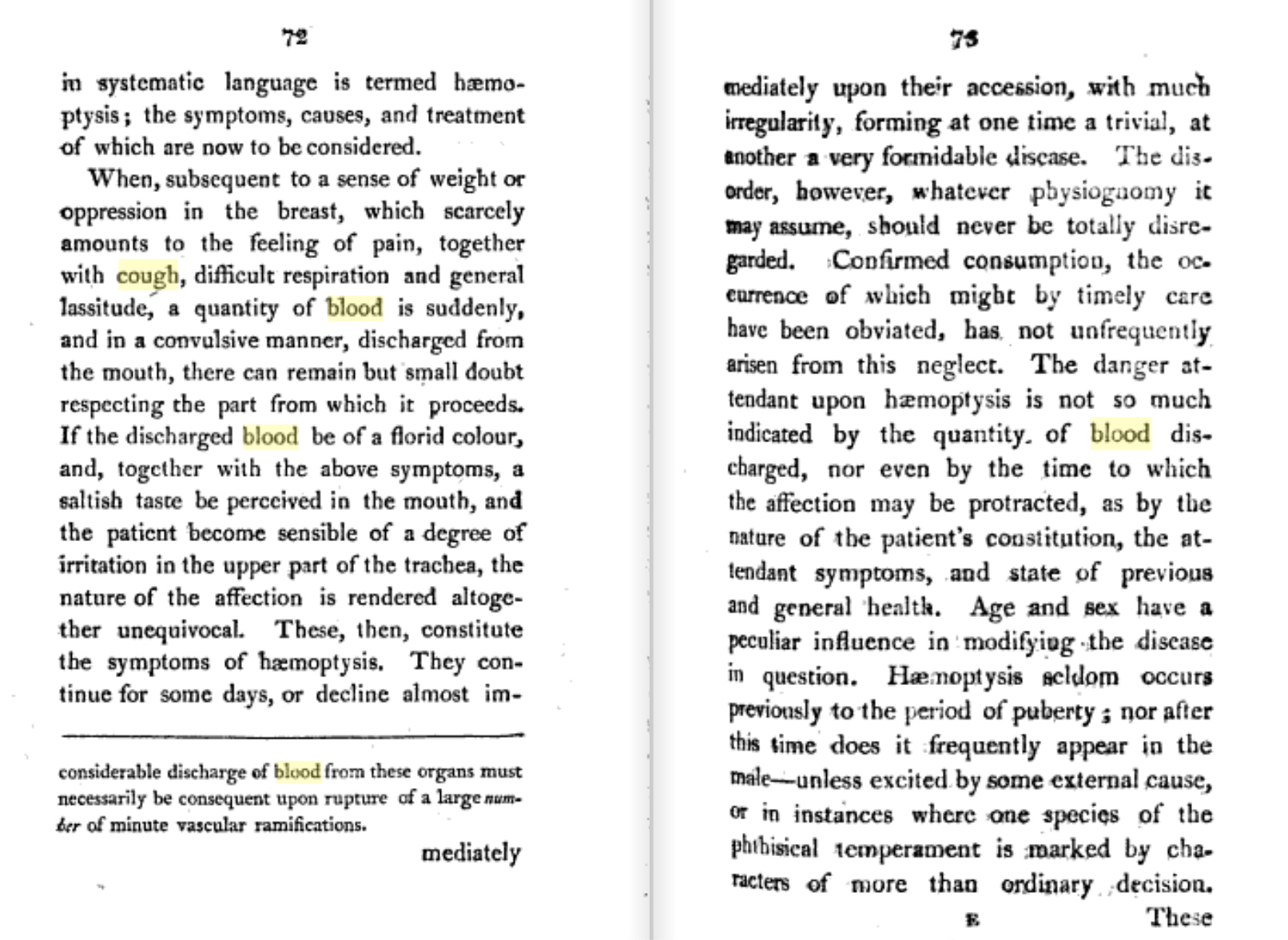

Keats, with his medical training—and from seeing his younger brother, Tom, through the illness of consumption until Tom’s death in

late 1818—recognizes from the colour of the blood (being oxygenated, and therefore

a brighter

red) that it comes from the lungs, and not, for example, from his throat, which would

be of a

darker colour (known as venous blood). Keats had also witnessed his mother die from

consumption. In short, Keats knew something about his condition. Keats, then, recognizes

that

the coughed-up blood does indeed likely signal consumption, the slow, nasty illness

also

sometimes referred to as the white plague or white death (the disease also gained

the mantle

of the robber of youth

), but what we know as tuberculosis—TB. No one yet knew with any

certainty that it was an infectious, airborne disease. Many thought it was inherited,

or that

it was something like cancer. About one out of four/five deaths in Keats’s time was

caused by

consumption (with an even higher rate in London at the time), and it is almost certainly

the

most deadly pathogen in human history.

Keats disagrees with a shortly-following diagnosis by a doctor that his lungs are

clear. He

will receive the same and obviously incorrect assessment later in the month, with

one

diagnosis suggesting that Keats’s illness might be psychosomatic. A week or so later

after his

hemorrhage, Keats describes that night, when so violent a rush of blood came to my Lungs

that I felt nearly suffocated

(?10 Feb, to Fanny

Brawne). To his younger sister, Fanny, he

writes about his carelessness in being caught out in cold: From impudently leaving off my

great coat [which in late December a doctor advises him to buy] in the thaw I caught

cold

which flew to my Lungs

(6 Feb). Keats has for some time feared the bad weather, and a

chronic sore throat and occasional fevers have plagued him for more than a year and

a half,

and may have been lingering signs of the illness—it can infect and then linger (wax

and wane)

for up to a few years before it fully shows itself. There is a reasonable chance that

his

chronic sore throat involved TB in his larynx.*

And to Fanny Brawne, his betrothed, who lives

next door in the other half of Wentworth Place—quite literally, on the other side

of the wall,

where he could not just imagine her presence but constantly hear it and on occasion

see her—he

writes a note the day after the hemorrhage: They say I must remain confined to this room

for some time. The consciousness that you love me will make a pleasant prison of the

house

next to yours.

But being next door to Fanny also grows to have

the opposite effect: anxieties, uncertainties, and fears will come to conflate with

love,

passion, and guilt—guilt for confining her because of his condition, and then putting

upon her

his dark fate. Keats refers to his nervousness, anxiety, and depressed state of mind

throughout the month. He suggests to Fanny that they break off their engagement.

Illness,

he writes, stands as a barrier betwixt me and you!

With the presence of Fanny and the possibility

of death before him—and with his brother George

now once more recently departed for America; with Tom having passed away just over

a year ago

dying from the same illness he likely has; with his finances dire; with his younger

sister

sometimes sequestered from him by the family guardian; with public indifference to

his poetry;

with tiring of some of his friends despite their acknowledged kindnesses; and with

having

loved the principle of beauty in all things,

anxious

thoughts understandably press upon him in the middle of the night: he fears he

has left no immortal work behind me,

he writes in a note to Fanny Brawne. How wrong he is.

Poetry, then, is not part of this month, and neither is much hope, even if he does

think of

completing his comic fairy poem, The Cap and Bells; Or, The

Jealousies, at some future date (he doesn’t). In a note to Fanny Brawne written during February, he says, I am recommended

not even to read poetry much less write it. I wish I had a little hope.

Keats muses upon

how he has, for the last six months or so, lost his feeling for natural beauty, but

now he

affectionately thinks about the beauties of Nature

—on every flower I have known from

my infancy

—while he watches the comings-and-goings outside his parlour window (letters,

14 Feb). Some of this is slightly overstated, since at least in Winchester in August

and

September he is greatly touched and inspired by Autumn’s warm, even chaste,

beauties

(letters, 21 Sept). But that must seem like years ago, given his condition and circumstances.

By the end of month, Keats reports feeling somewhat better; but this is only a brief reprieve from the horrible disease, one that takes its time, that comes and goes, as it wastes away—consumes—its victims. So as the illness steadily progresses, Keats’s own poetic progress ends; his reputation as an exceptional poet, however, is just beginning, and unlike the characteristic feature of his illness, it will not, over time, waste away.

_____________

*My sincere thanks to Dr. Marc Lipman for his consultation about the symptoms and

onset of

tuberculosis and Keats’s account of it. Dr Lipman: Certainly the natural history of

untreated TB was one of waxing and waning for many people—and this could be for years.

Hence

it may be that Keats had TB involving his larynx, which gave him the sore throats,

as well

some disease in his lungs (the chest infections). What then probably happened, when

he found

(bright red) blood on his pillow, was that his TB had progressed to develop cavities

in the

lungs, and one of these had eroded into a blood vessel that was being supplied by

arterial

blood, which is a brighter red than venous blood as it contains more oxygen, and at

a higher

pressure than the rest of the blood vessels in the lung. As a medical trainee, he

recognised

this—and its significance: namely that the bleeding was likely to be of much greater

consequence if it continued. Hence his comment that he was done for. This also fits

with the

findings of extensive disease reported following his autopsy (where, incidentally,

his lungs

would have been very infectious to others).

Marc Lipman is Professor of Medicine at University College London and Consultant in

Respiratory & HIV Medicine and Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust. He is Director

of

UCL-TB, UCL’s cross-disciplinary TB research grouping.