January 1820: George Comes, George Goes; Hope despite T Wang-Dillo-Dee

; Urn

Published

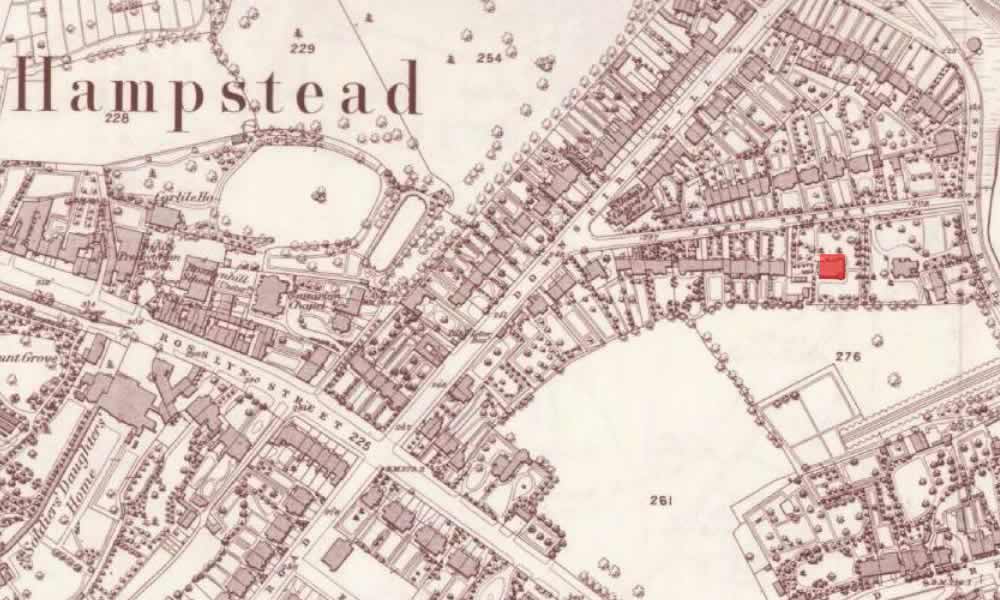

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Keats’s younger brother, George, arrives from America early in the month; he leaves 1 February. George’s mission is to clear up and make his claims for his share of family funds, which in part is now tied to the death of their younger brother, Tom, and the resulting redistribution. George aims to re-finance himself, having lost most of his money in a dubious business venture in America.

In December, Keats, aged twenty-four, works hard to help George by meeting with the usually truculent trustee of the family money and family

guardian, Richard Abbey. When George’s deal is

worked out, George reports that Abbey behaved very kindly to me

(30 Jan). Keats feels

very differently: Abbey, he believes, has been stingy in even allowing Keats open

access to

meeting with the youngest of the Keats siblings, Fanny—and also denied her pocket

money. Keats

also notes that Abbey, By detaining money from me and George when we most wanted it he has

increased our expenses.

Keats’s conclusion: Abbey has not behaved well

(letters,

14 Feb). The general feeling (with Keats himself and a few of his friends) is that

George

somewhat aggressively assumes more than his fair share of the estate, though this

may not have

been the case. (One of Keats’s closest friends, Charles

Brown, believed George swindled Keats out of money.) To the end of his life, Keats

never trusts Abbey. Keats is never aware that a significant inherited sum (perhaps

around 800

pounds, via his maternal grandfather) is waiting for him through the court, where

it has been

accumulating interest. It appears Abbey himself might likewise not have known about

these

other funds.

Besides dealing with Abbey during January, George and Keats socializes quite a bit with mutual friends—dancing, dining, and partying. George makes some copies of Keats’s poetry, including Ode to a Nightingale (at this point it seems to be called The Nightingale).

Despite the wealth of social activity—or perhaps because of it—Keats feels idle and

unsettled. In writing to George’s wife in America

over 13-28 January, he expresses, somewhat playfully, that, Upon the whole I dislike

Mankind,

and, in particular, self-interested types. He also notes the boring

predictability in socializing with certain friends, as well as a vague dullness

and

disenchantment with life, and London life in particular. Keats’s conclusion: like

people for

their good parts

and ignore the dull process of their every day Lives

(letters, 15 Jan). He has thoughts of retiring to the country, where he can avoid

news.

Somewhat whimsically, he also wishes he had money enough to do nothing but travel about for

years.

He nonetheless takes time to have some fun in his long journal letter, including

a brilliantly humorous typology of three of his witty

friends, as well as having some

fun at those who have no wit at all, each distinct in his excellence.

T wang-dillo-dee,

Keats writes eight times to encapsulate random examples and sites of

nonsense he observes, including modern poems, some lords, London, and Earth itself

(letters,

17 Jan). This is, in fact, pretty funny.

In January, Keats, aged twenty-four, still maintains hopes for making some money from

a play,

Otho the Great, co-written with his generous and very close

friend Charles Brown, his roommate at Wentworth

Place. Keats initially believes the play will make him a badly needed 200 pounds,

while also

raising his name above the vulgar

reputation he felt he had with the literary

fashionables

(letters, 17 Sept 1819). Keats records that the play, though accepted by

Drury Lane for later in its theatre season, has been withdrawn since they want it

staged

sooner; with Brown, some revisions are now made in order to submit it to Covent Garden.

Nothing, however, comes of the play,* and Keats during this cold winter writes almost

nothing.

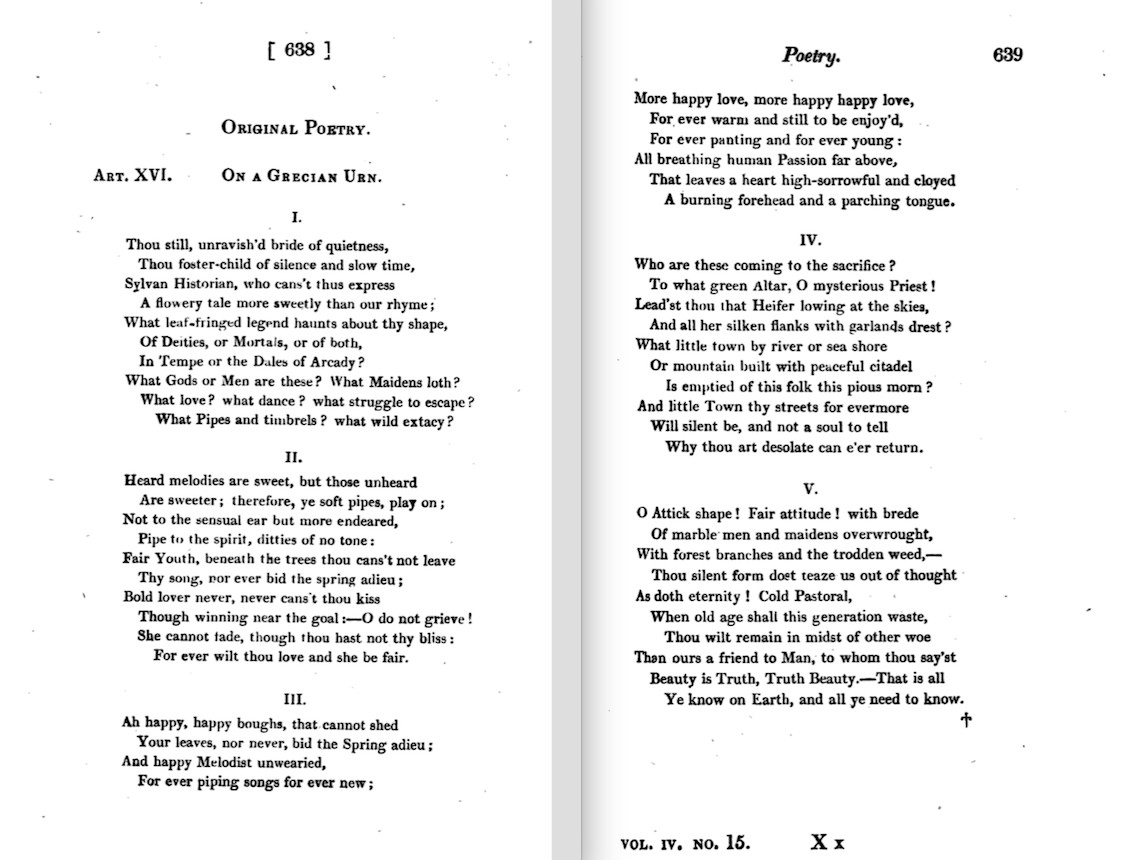

The only good news, in a way, is that one of his best poems, Ode on a Grecian Urn, is published

in Annals of The Fine Arts. The poem, probably written in

the spring of 1819, and perhaps May, reflects Keats’s mature and much-desired ability

to

capture a subject with controlled intensity, and it articulates and achieves what

Keats posits

in his poetics, that beauty is not bound by truth, fact, or reason, and thus beauty

has its

own unalterable value that will surpass knowing and outlast time. Thus art is a high

ideal

that counters and even distinguishes our mortal station. The unknowable but beautiful

urn, in

fact, is a symbol of the kind of poetry that Keats himself attempts to put before

us: we do

not know the truth

of the urn (who are these figures? where are they going? what are

they doing? who made the urn?), but we nonetheless know the urn is beautiful and possesses

imaginative potency that speaks beyond its own material and historical circumstances:

it takes

us out of ourselves and beckons our own imaginative capabilities. The urn’s qualities,

then,

mirror Keats’s poetic aspirations: to write poetry that defies mortal time and rational

knowing—poetry that will evermore remain a friend to man

(line 48) despite the burden

that our existence puts upon us. The poem pushed in this direction is an allegory

of Keats’s

writing.

These powerful conclusions have been on Keats’s mind since late 1817, when he writes

that

with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes over other consideration, or rather

obliterates all consideration

(letters, 21/27 Dec. 1817). Keats by 1819 has become that

great poet,

though his greatness will only begin to be (so to speak) writ large until

after his death. Characteristically, Keats’s epistolary poetics both anticipate and

propel his

poetic progress. For the first two or three years of his life as a declared poet

(approximately late 1816 to late 1818), rather than finding that mature voice, Keats

too often

ineffectually writes about desiring to be an enduring poet, or he writes poetry that,

too

self-consciously, he hopes will prove that he can simply write poetry. He’s a poet

in search

of a justification of his purpose as a poet. Those earlier years are, then, his apprentice

years—could they be anything else?—and the vast majority of the poetry lacks direction

in

subject, voice, and form. By 1819, Keats finds his stance of the great poet

mainly via

lyric forms that often pit binaries both against themselves yet simultaneously blended;

he

achieves this via a kind of poetic equipoise that often, in complex ways, revolves

around the

tensions of thought and sensation, which might be called his primary blended binary.

By late

1919, Keats seems to have neither peace of mind nor strength of body to find this

voice again.

*Otho the Great is not staged in the US until June 2016 (in Chicago, produced by Frank Farrell, and running 11-25 June); the play’s title is slightly jigged: The Dark Ages: Otho the Great. Reviews were generally quite good. The play’s world premiere is in London, 26 November 1950, put on by the Premier Theatre Club, St. Martin’s theatre; Robin Bailey plays Ludolf.