24 November 1818: A Dying Brother’s Only Comfort & Hazlitt’s Influence

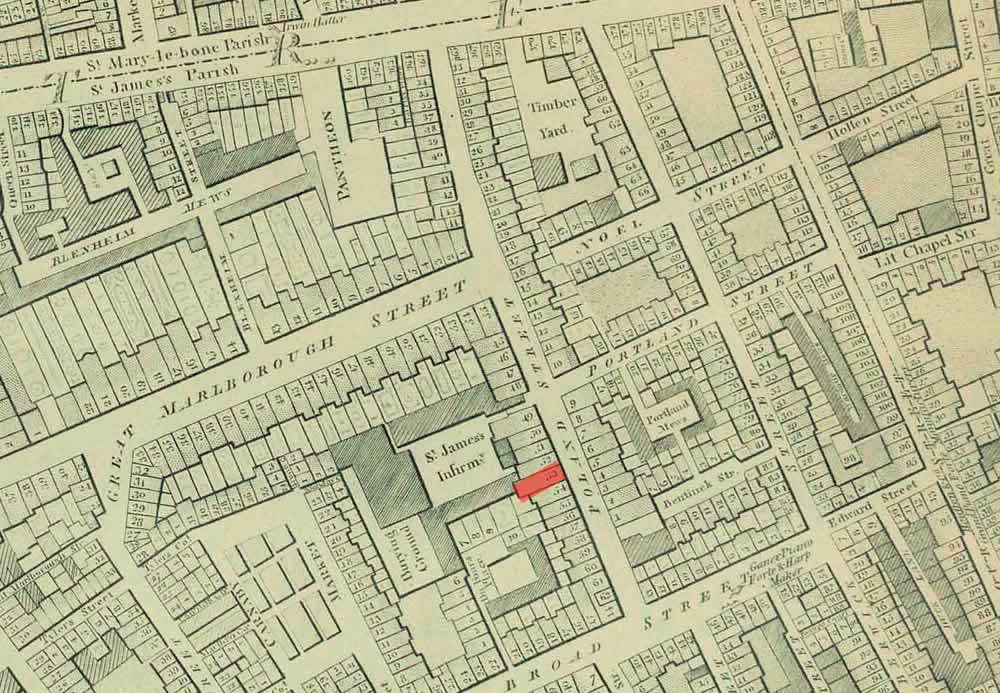

50 Poland Street, London

Where Keats’s much respected, supportive, and witty friend James Rice, an attorney, lives. On this day, Keats writes to him to explain what seems to be a social misunderstanding involving a meeting with Rice (and possibly another) in the morning. Keats tries to avoid and to explain hurt feelings.

November is difficult for Keats, though earlier in the month he receives a gift of

25 pounds

from someone calling him- or herself P.

Fenbank,

along with a lackluster though flattering Sonnet to John Keats that praises him as a Star of high promise

who

illuminates this dark age

: the poem bestows Keats with mild light,

clear beam,

and bold integrity of song

that will shine through all ages.

This somewhat bolsters his spirits, though later, with a little pride, he writes that

the

present galls me a little

(29 Dec).

But this month is dominated by caring for his younger brother, Tom, just turned nineteen, as he slips toward death from

tuberculosis. Keats has been nursing him almost continuously since returning from

his northern

walking tour, mid-August. In October, writing to his other younger brother George and his wife Georgiana in America, he sadly admits that he is Tom’s only comfort,

and he

calls the situation my Misery.

His own emotional struggle with Tom’s grim condition

holds him back from being able to write much about it (letters, 14, 16 Oct). On the

evening of

the last day of November, it is clear that Tom’s death is very near.

Not only does caring for Tom exhaust and depress Keats, but it also prevents him from any sustained work on his ambitious Hyperion, which he has recently begun. He’s been thinking about the topic (the displacement of the Titans by the Olympians) for almost a year. Relative to his earlier long and at moments flighty poem Endymion (published April 1818, and which he was anxious to put behind him), he sees Hyperion as more deeply abstract, unsentimental, and classical. He’s right. There’s little poetic prettification and affectation in the poem.

Tom’s grave condition also pulls Keats away

from the rounds of socializing that he normally keeps up with his London and Hampstead

friends. During the period of caring for Tom, and even when he goes out more frequently,

he

notes that it leaves him without anything fresh

to speculate upon.

Until

mid-October, at least, his actual poetic progress is stymied: the way I am at present

situated, I have too many interruptions to a train of feeling to be able to write

Poetry

(16 Oct). This, however, does not stop Keats thinking about the kind of poetry he

wants to

write and the kind of poet he wants to become.

So in November, we have to imagine Keats at Tom’s bedside, with no family support; with nagging financial issues and the family estate clogging his energies (he sees the family guardian, Richard Abbey, a number of times in late October and into early November); with further struggles with Abbey about having his younger sister, Fanny, get permission to visit with Tom; with his fears about his own health issues (a chronic sore throat); with recent malicious reviews of his poetry in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and The Quarterly Review to contend with; and with the desire to write an epic poem of significant (Miltonic) scope, pitched at an entirely new level and style that might counter his dismissive association with Leigh Hunt and the so-called Cockney School of poetry, which Hunt is charged with leading. Keats’s friends notice his overwrought state. Behind all this must be Keats’s associative feelings of about eight years before when he witnessed his mother’s fall to the same agonizing, wasting illness. At this point in medical history, no one knows that TB is highly contagious.

Along with attempts to move forward with Hyperion (which

contains perhaps his best poetry written thus far, though he abandons it for a few

months),

Keats may have written a few shorter poems during November. But it would be difficult

for this

poetry not to be at least partially inflected by what literally stares him in face:

Tom’s agonizing descent. Given its subject, Keats

possibly writes Bards

of passion and of mirth in November: the poem idealizes poetry’s

immortal—heavenly—qualities, with the idea that these qualities with their wisdom

of sustained

melodious truths

might teach

those who suffer earthly inconstancies,

weaknesses, and doubts. Keats writes that the poem is on the double immortality of

Poets

(2 Jan 1819, in a letter begun 16 Dec).

Perhaps significantly, Keats inserts the Bards of passion poem into a

letter just after taking the trouble to quote at length his friend and critical mentor

William Hazlitt, where Hazlitt describes William Godwin’s genius

: the key, Hazlitt

writes, is Godwin’s study of the human heart

and his empathetic imagination. This

obviously resonates with Keats. Why? Because, in fact, these have become central to

Keats’s

poetics—to his subject (the human heart

), and to how he will explore his subject (with

an empathetic imagination). That they in part derive from Hazlitt is not surprising,

given

Keats’s respect for Hazlitt as well as how Keats’s most famous critical

formulations—Negative Capability

(letters, 21/27 Dec 1817) and the

camelion Poet

(letters, 27 Oct 1818)—to a significant degree are also adapted from

Hazlitt, as are Keats’s ideas about artistic intensity, disinterestedness, and the

interpenetration of truth and beauty.