2 August 1818: Mistiness: Ben Nevis & the Hope for Loud Muses

Ayr to Ben Nevis, Scotland

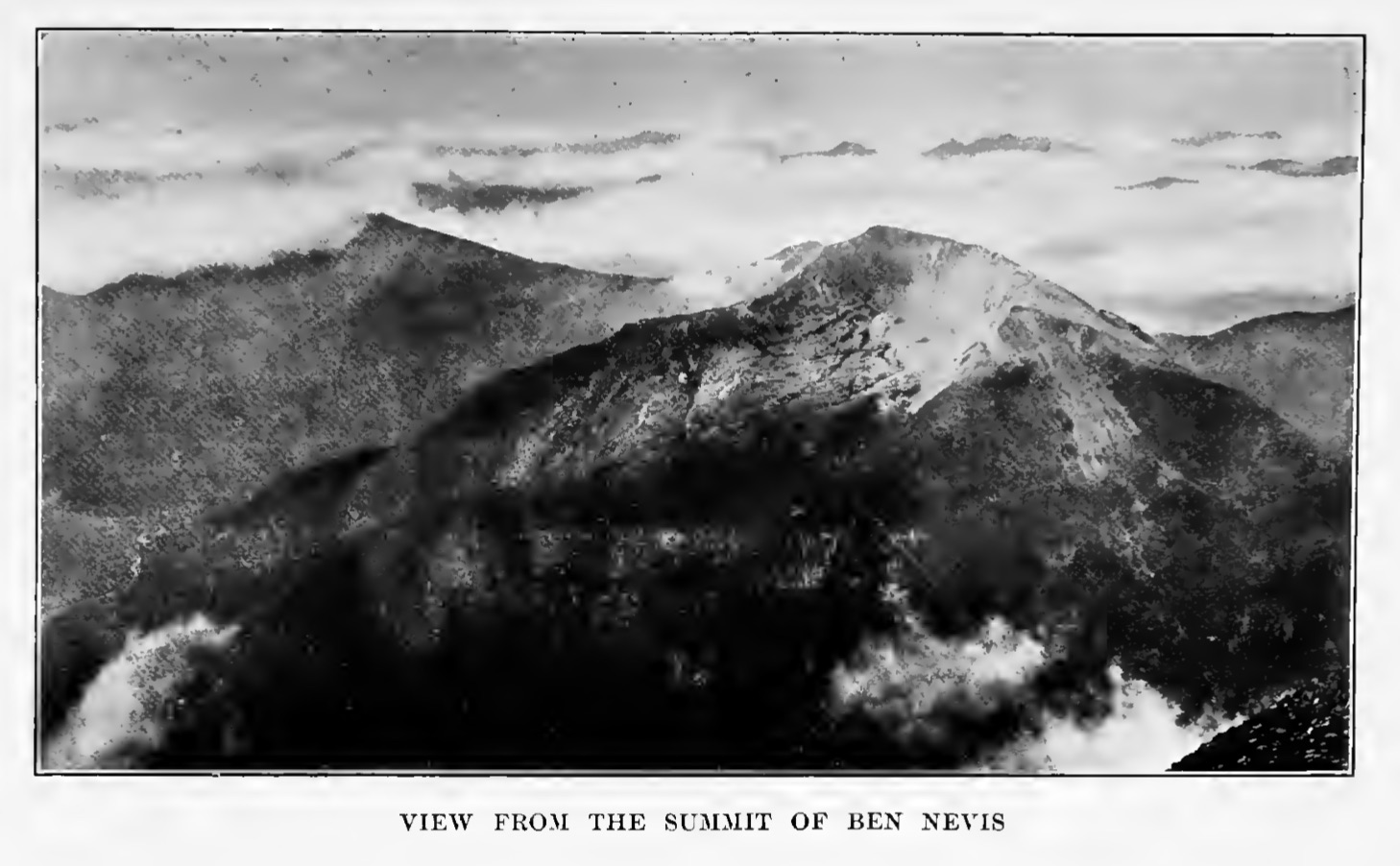

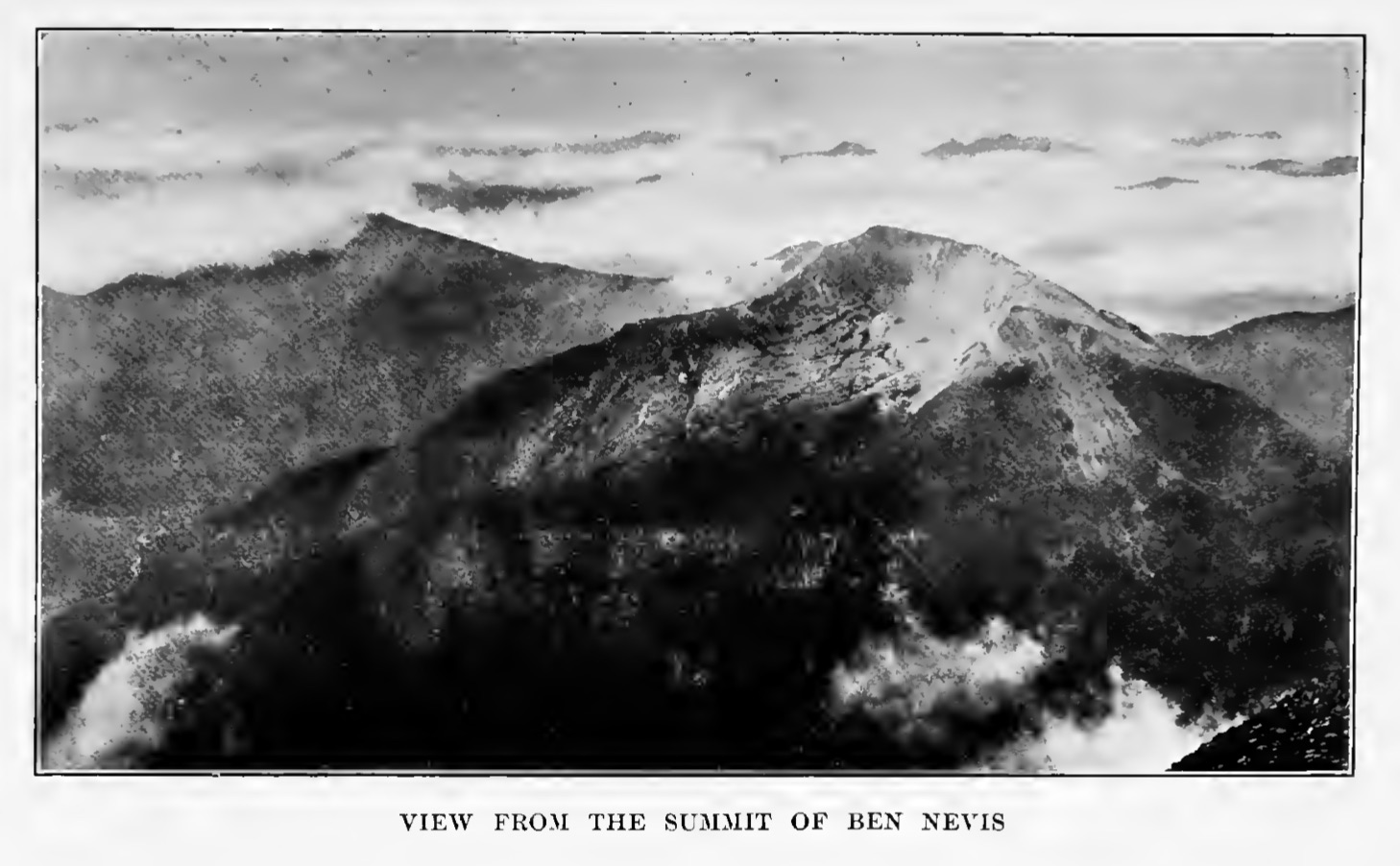

This is the highest point of Keats’s northern tour—literally, at least: Keats (aged 22) climbs Ben Nevis, the tallest peak in the British Isles at 4,413 feet, and part of the Grampian Mountain range of the general Scottish Highlands. The first recorded ascent of Ben Nevis is in 1771, by a botanist, James Robertson.

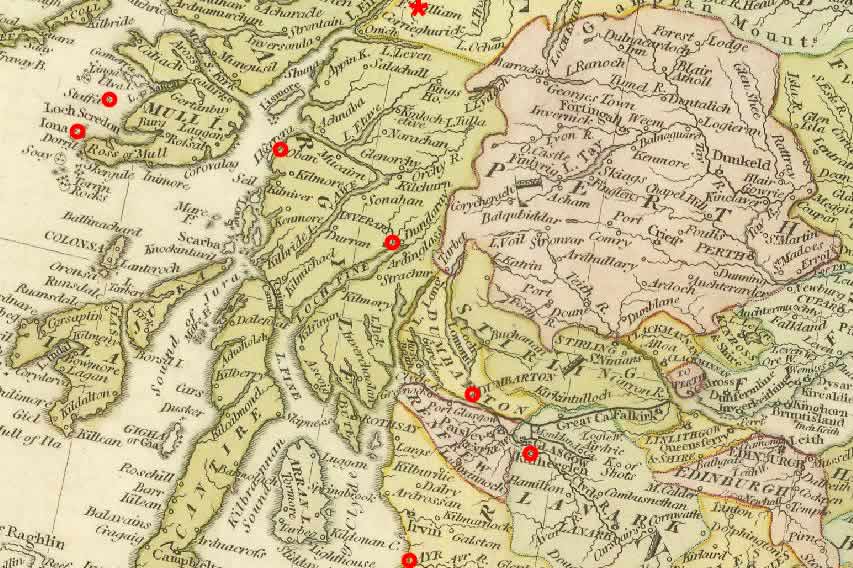

The climb takes place during a northern walking tour with his good friend Charles Brown. When completed, they will have covered something like 650 miles. The tour begins 25 June, going from Lancaster to the Lake District, where Keats attempts to come to terms with the impressive countenance of the landscape, which challenges some of his ideas about the imagination as a way of knowing and perceiving; he also attempts to visit William Wordsworth, but the great poet is out canvassing for the Tory party, which saddens Keats. By 1 July, they are in Dumfries, Scotland, where, the same day, they visit the tomb of Scotland’s most famous poet, Robert Burns. A brief detour to Ireland as far as Belfast reveals more striking poverty, and it is not of their liking. By 11 July, they are in Ayr, Burns’s birthplace. Keats finds it difficult to throw off feelings about Burns’s misery and the complex nature of Burns’s fame.

Keats and Brown pass through Glasgow on the 13-14 July. They arrive at Inveraray a few days later. Within a week, they are in Oban and off to the Island of Mull (338 sq. miles), and then to the small island of Iona (3.4 sq. miles), with its absorbing history, ruins, and graves. On the 24th, they see Fingal’s Cave (a sea cave) on the tiny island of Staffa (.8 sq. miles); the natural features (the basalt, hexagonal columns) are on a scale that inspires Keats to imagine titanic struggles.

Keats also begins to develop throat problems. An indifferent diet (coarse

food, he

calls it), crude and sometimes smoky accommodation, getting soaked and cold, and becoming

completely exhausted on testing walks do little to help his slumping health. He daydreams

about having a comfy chair and a Cup o’ tea

in Hampstead.

Negotiating loose, awkward stones makes the ascent of Ben Nevis tough—and what Keats

calls

the vile

decent tougher, even with (or maybe because of) a few glasses of whiskey.

Keats is nevertheless struck by the enclosing, blinding mist, the huge crags, and

the prospect

from such a height. But what challenges his senses most are the chasms: they are,

he writes,

the most tremendous places I have ever seen—they turn one giddy if you choose to give

way

to it

(letters, 3 Aug).

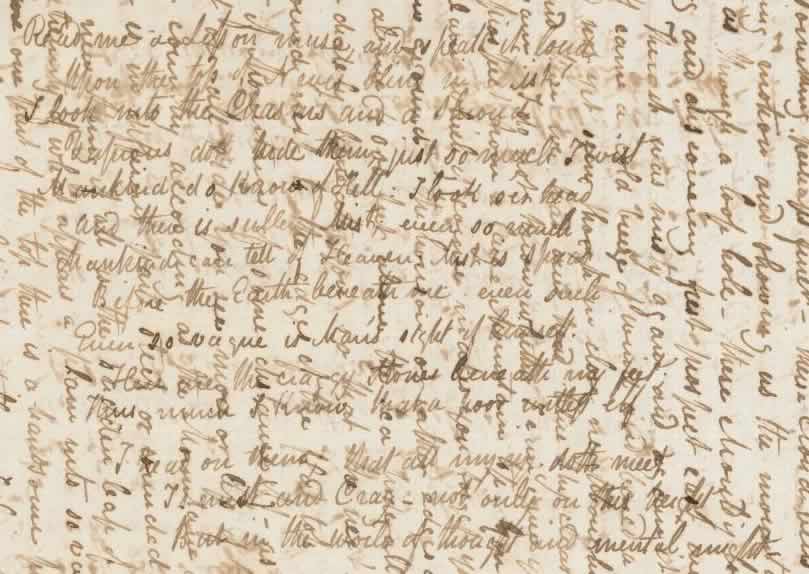

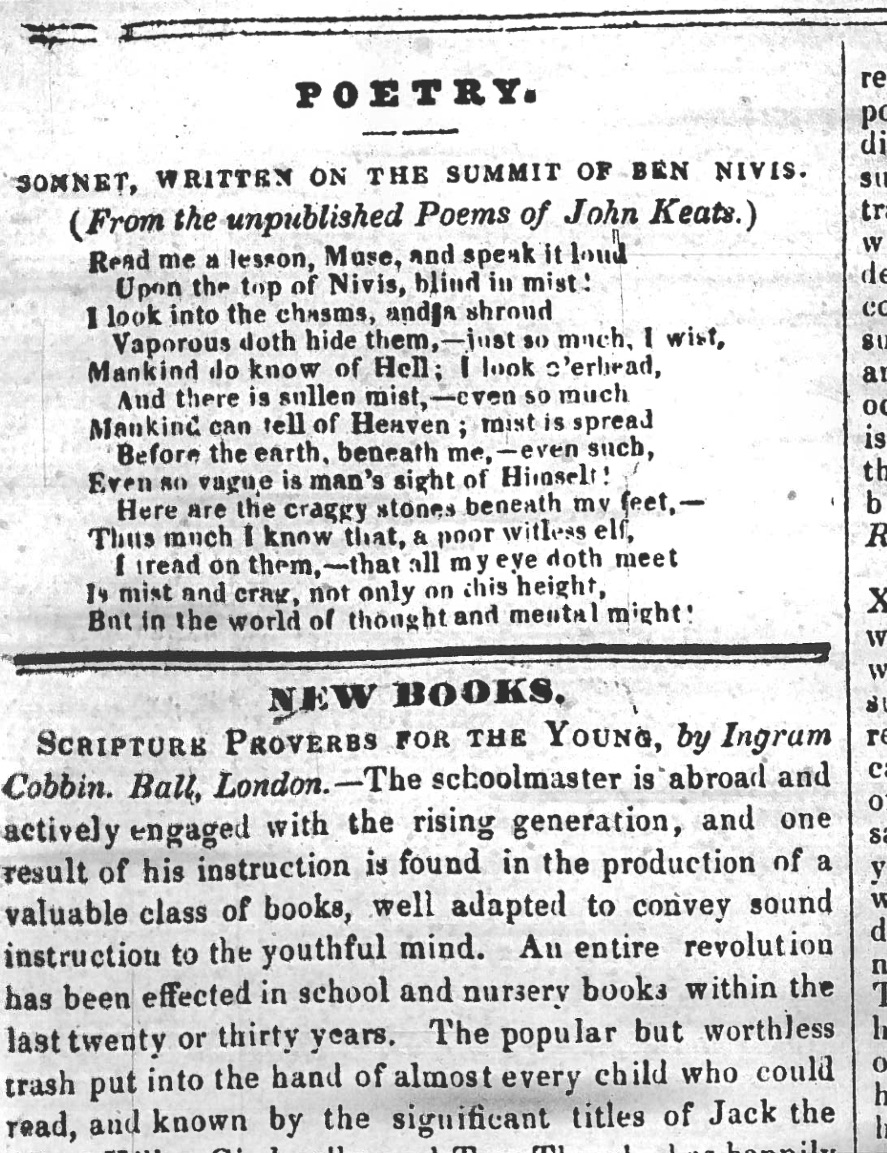

Sitting on a precipice near the top of the mountain, Keats drafts a poem—Read me a lesson, Muse,

and speak it loud—which he then re-drafts (written cross-hatched) in a

letter to his younger brother Tom, 3/6 August.

The crags, precipice, chasms, stones, and mists of Ben Nevis make it into the sonnet

(mist, in

fact, four times), as does Keats’s longest-lasting topic: desire for inspiration to

provide

some kind of lesson.

There he is, on top of a mountain, imploring the Muse

to

speak to him so that he has inspirational insight despite his physical blindness.

Keats

dramatizes himself looking down, looking up, and looking out; nothing is knowable—hell,

heaven, or the earth. So, despite his high place, except for the craggy stones

at his

feet, he cannot see into the world of thought and mental might.

Things remain in a

mist—shrouded, vague, and unresponsive. Keats, then, represents his own undetermined

direction—the only clear things are those uneven elements closest to him—but, in the

spirit of

transforming the personal into the universal, Keats also captures the sullen

view of

humanity—and the theme of how little we know.

In this sense, the poem, though not a great one, and with much of it tonally banal,

nonetheless hints of a vital Wordsworthian

direction: the uncluttered desire to see into the life of things despite vague

uncertainty. Besides the Romantic sublime, the poem also connects with the Romantic

trope of

skeptical knowledge, of not being able to see into the dizzying abyss (used, for example,

by

his acquaintance and exact contemporary, the poet Percy

Shelley). The poem does, however, over-employ the idea of mist

to suggest

(what else?) blindness, mystery, and the limitations of understanding. This faintly

anticipates how he will go on to deal with topics in much of the great poetry he writes

over

the next year.

From another perspective: While the poem marks an advance on his earlier standing-on-top poem—I stood tip-toe upon a little hill, written December 1816—it also shares the topic of desiring poetic inspiration by looking out from on high. The question remains: By looking out, can we (or he) look within? His earlier poem reveals the relative immaturity of Keats’s imaginative capabilities, where the ostensible vision offers little insight; this later poem hints at demanding something more complex from visionary capabilities—negative ones, in fact.

In terms of Keats’s poetic progress, the moment perhaps also reduces to an allegorical

one

tied to his time-line: Keats’s future outlook—his poetical prospect—is uncertain.

Again, the

imagery—of blindness, vagueness, vaporessness, being in a shroud, being in a mist—makes

this

lack of clarity clear enough. And in the end, Keats admits that the inability to see

also

applies to understanding the operations of the mind—including himself, a poor witless

elf.

Again, he waits for inspiration.

In a different vein, the encounter with Ben Nevis also inspires Keats to dash off a gleeful dialogue poem between Ben Nevis and a certain Mrs. Cameron, a climber of significant girth who wants to ascend the mountain, much to the mountain’s—Ben’s—utter disbelief. The poem—Upon my Life, Sir Nevis— may have been written to divert Tom, who is very ill, or perhaps Keats simply wanted to have some fun and pass a little time as self-diversion.

The northern trip does not rouse much in the way of penetrating poetry.

[For a detailed mapping of Keats’s walking tour, see Keats’s Northern Walking Tour.]