18 July 1818-August 1818: Tramping in the Highlands

Inveraray, Scotland

Mid-July: Keats (aged 22) and his good (perhaps closest) friend Charles Brown are about three weeks into a walking tour that starts in northern England.* His plan is to make the trip four months long, but health issues curtail the excursion considerably. Nonetheless, Keats and Brown cover more than 600 miles on foot. Keats is back in London and Hampstead by 18 August.

Brown, in a letter of July to a mutual friend, notes that Keats’s initial reaction

to

Scotland and the Scottish is to abuse both—Keats, being a bit nasty, in one of his

comments

claims Scottish women have large splay feet.

Here we might keep in mind two points;

first, that English tourism into Scotland was at the time quite common; and second,

given the

politics of the day, that English tourism into Scotland necessarily carried with it

something

close to what might be called cultural condescension—the gaze of the colonizer upon

the

colonized. This was not altogether lost upon Brown and Keats, who at moments are very

aware

that they are seen as the outsiders—this, despite Brown’s Scottish ancestry, with

part of

Brown’s motivation for the trip to search out just a little of that ancestry.

The trip begins 25 June in the Lake District. The landscape impacts Keats in exceptional and unique ways—compounded and complicated by William Wordsworth’s association with the area. By the afternoon of 1 July, Brown and Keats are in Scotland, where, the same day, they make it to Dumfries in order to visit the fairly elaborate tomb (mausoleum) of Scotland’s most famous poet, Robert Burns, built in 1817, just over twenty years after the poet’s death.

Keats and Brown then trek east. Keats is struck

by the poverty at least as much as by natural and historical elements. A short detour

takes

them into northern Ireland as far as Belfast, where the poverty is even more pronounced.

Returning to Scotland, they head northeast to Ayr, Burns’s birthplace. Keats imagines

finding

a desolated area, but he is unexpectedly struck by the natural beauty. Nevertheless,

Keats

finds it difficult to throw off feelings about Burns’s misery—his dead weight,

Keats

calls it (13 July, to Reynolds). Keats mainly

mulls over the discordant elements of Burns’s life and his poetry, but Burns also

turns him to

darker thoughts of his own mortality and poetic strivings. What is the meaning of

poetic fame?

What is the legacy of Burns?

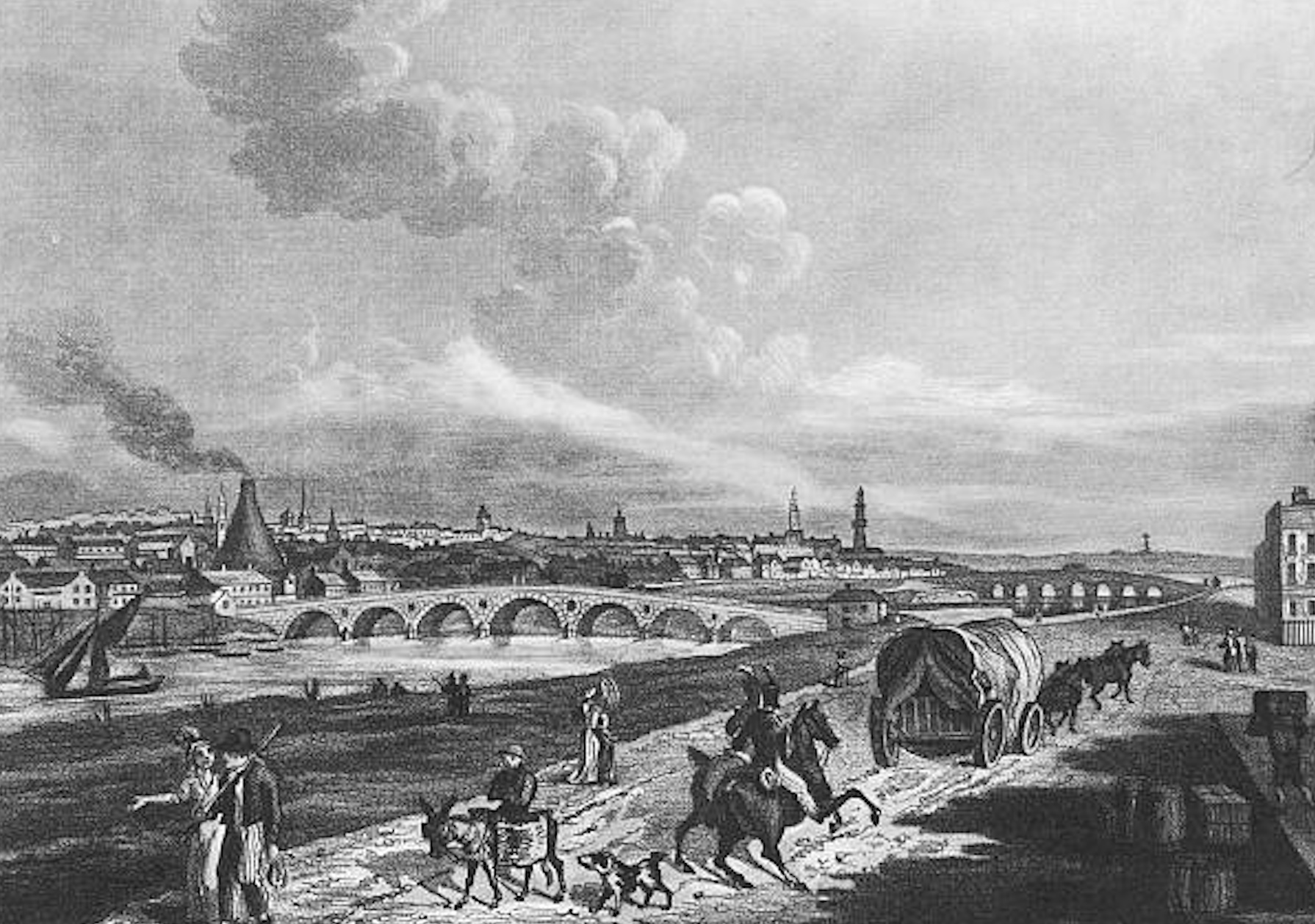

Keats and Brown pass through Glasgow on the

13-14th, which Keats records as a fine city, though they are stared at, and Keats

is accosted

by a drunk (letters, 13 July, to Tom Keats). By Inveraray, Brown suffers from foot

blisters

and Keats from the horrors

of the bagpipe (18, 20 July, to Tom). At times, they even

have to sleep in their clothes on dirt in smoke-ridden huts (letters, 23 July). A

minor

highpoint: on the 24th they visit ruins on the island Iona and the grave where Macbeth

and

other Scottish kings are buried.

But it is in a letter to his friend Benjamin

Bailey on 18 July that Keats, with a sane and sober Mind,

reveals something

about himself and his motivations. He confesses his tendency to carry all matters to an

extreme

and with little self possession,

which tells us something about the

tensions of empathy and intensity that will manifest in some of his poetry. Keats

also

attempts to describe his anxieties about being in the company of women: When among Men I have no evil thoughts [and

am . . .] free from all suspicion and comfortable. When I am among Women I have evil

thoughts . . .

. Marriage for Keats is, it seems, not viable: besides his love of

solitude and freedom, as well as his attraction to socializing with like-minded men,

he

wonders if marriage might compromise his poetic aspirations.

In this letter, Keats also writes about the intended larger purpose of his walking

expedition: I should not have consented to myself these four Months tramping in the

highlands but that I thought it would give me more experience, rub off more Prejudice,

use

me to more hardship, identify finer scenes, load me with grander Mountains, and strengthen

more my reach in poetry, than would stopping at home among Books . . .

. In short, Keats

has a purpose: increase experience, decrease prejudice, toughen up, and load up with

grander

imagery—all in the name of expanding poetic potential, more so than just studying

and reading.

But Keats implies that the trip, thus far, though hardening him, has not yet met his

goals. He

admits that even the solemn

power of mountains is wearing away.

What will weigh

more heavily, perhaps, is more the accumulative experience rather than the particulars

of the

wearying trip that is cut short by health issues. Keats remains a poet in search of

both

poetic material and poetical identity.

Later in the month, Keats’s chronic sore throat will return. Having at times to sleep in their clothes on the damp, dirty floors of fairly primitive huts will not help. He is also becoming homesick.

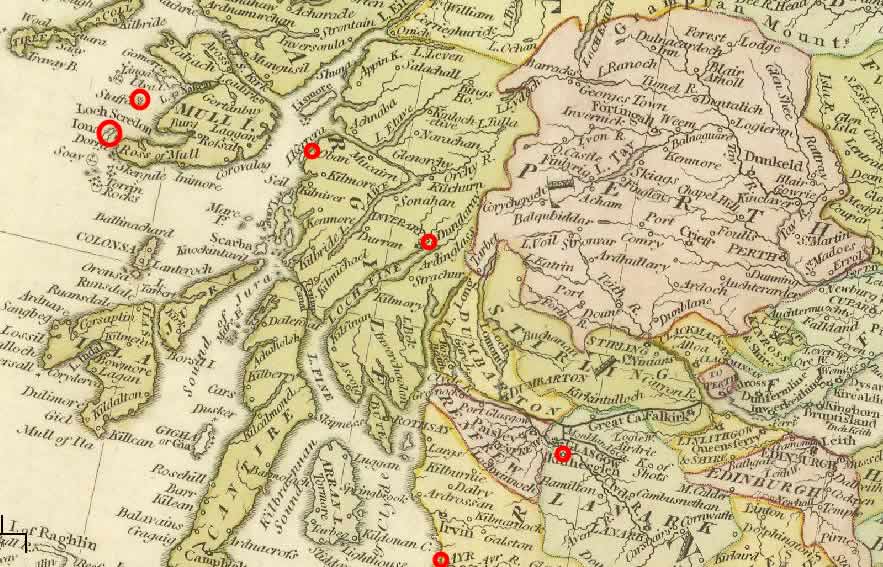

*[See here for interactive, annotated map with a time line: Keats’s Northern Walking Tour with Charles Brown.]

![When among Men I have no evil thoughts [and

am . . .] free from all suspicion and comfortable. When I am among Women I have evil

thoughts . . . When among Men I have no evil thoughts [and

am . . .] free from all suspicion and comfortable. When I am among Women I have evil

thoughts . . .](images/facsimiles/WhenIAmAmongWomen.jpg)