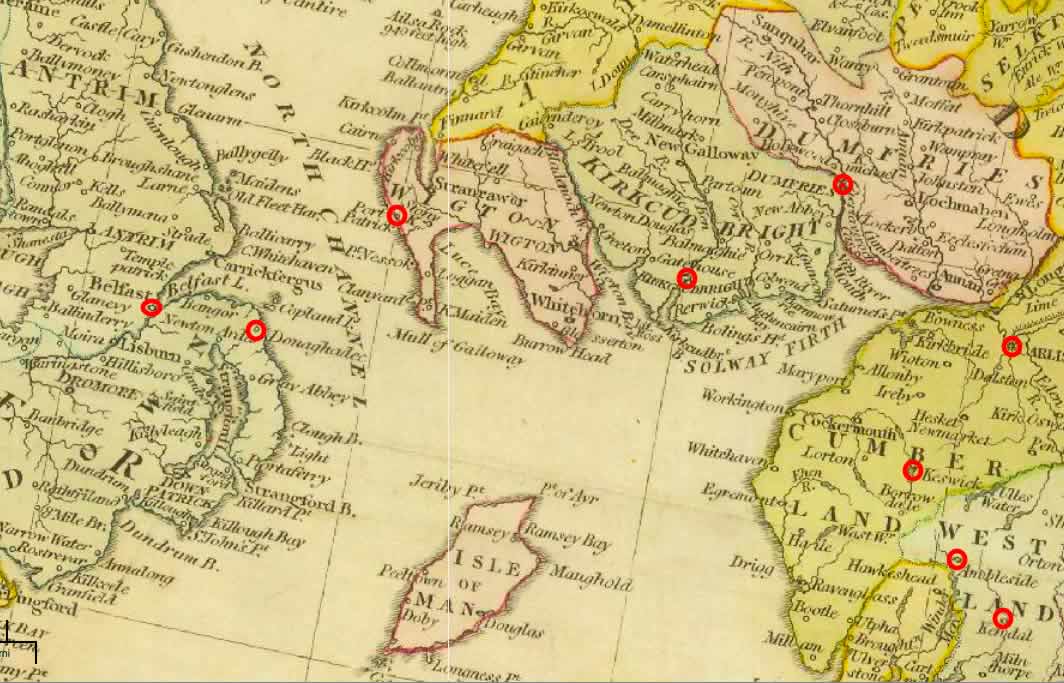

1 July 1818: Robert Burns, Dirty Bacon, & the Irish Duchess of Dunghill

Dumfries, Scotland

With his close friend Charles Brown (aged 31), Keats (aged 22) is in the early stages of an ambitious walking trip north, though they also at points take coaches. They often average between 15-20 miles/day (sometimes that much even before breakfast), and, in total, they cover over 600 miles.

Brown and Keats are likely armed with one of the very popular tourist guides of the

time,

quite possibly The Traveller’s Guide through Scotland, and its Islands (6th

edition1814; 7th edition 1818). In the Guide, Brown and Keats would have found

detailed information about counties and parishes, a listing of mountain heights, distances,

scenery, drawings of geographical features and historical landmarks, population, listings

of

inns, roads, paths, and, of course, maps. Tourism into Scotland—the highlands—was

something of

a fashion at the time, and the English look

upon the Scottish is no doubt tinged by

what we might call the colonizer’s gaze. And, according to Brown’s account of the

trip, he and

Keats were hardly inconspicuous travellers.

Keats and Brown begin their trip 24 June from Lancaster. They have just parted with Keats’s brother, George, and his wife, Georgiana, at Liverpool, 23 June; like many British of the era, they are emigrating to the US in search of opportunity and land. A loss for Keats: he is very close to George, who, although younger than Keats, has to some extent buffered his older brother from, so to speak, the murky business of the world. A gain for us: Keats begins to write long journal letters to George and Georgiana that significantly broaden our understanding of Keats.

The expedition north takes Keats and Brown

through and around the Lake District, from Kendal and Ambleside and up to Keswick.

The

landscape—mountains, waterfalls, lakes, perspectives—genuinely astonishes Keats, so

much so

that it challenges his ideas about the relationship between reality and imagination.

This

becomes important as Keats attempts to understand the imagination as a form of knowing,

and

relative to his developing sense of rationality, judgment, sensation, and experience—and,

dare

we say it—reality. Keats attempts to express what exactly it is that makes him respond

so

profoundly. These elements of the landscape seem to have a tone or intellect

of their

own, he writes. So too does the moment inspire future work: he hopes that from the mass of

beauty which is harvested from these grand materials

he will learn and write more

than ever . . . for the relish of one’s fellows

(25-27 June). In a way, Keats is

responding to the landscape in the way he responds to his encounters with great literature.

This all connects to the questions of the age: Does the landscape (or nature) have its own

independent power, or does the mind, via the capable imagination, constitute or create

this

power? Or is it some deeper intermingling of the two? Where, exactly, does the sublime

exist?

The two travellers then (30 June) head north to Carlisle on their way to Scotland, where, despite being tired, they spend some of the next day sightseeing. Keats is back in London mid-August.

Another way to describe this moment: Having left Wordsworth country, Keats enters Robert Burns country. Keats is also aware that he is following in the footsteps of Wordsworth, who, in 1803, with his sister, Dorothy, search out Burn’s resting place. Keats is fully conversant with Burns’s life and poetry; Brown (whose ancestry on his father’s side is Scottish) is likewise very much a Burns fan.

By late afternoon, 1 July, Keats and Brown are at St. Michael’s churchyard in Dumfries, where Burns (1759-1796) was initially buried in one corner of the churchyard; but now he is memorialized a just-completed impressive classical mausoleum. Keats is struck by its size, but he questions if the Grecian style of the marble building fits with landscape—and it certainly contrasts with the humble cottages and very apparent poverty throughout the area.

Although Burns does not for Keats carry the

influential weight (or burden) of Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, or even Spenser, the Scots poet represents the self-directed though tragic outsider—a

psychological and cultural positioning with which Keats no doubt identifies. Keats

composes a

sonnet—On

Visiting the Tomb of Burns—but he does so, he writes, in a strange mood

(letters, 1 July); he does not know quite how to respond. The poem does, however,

clarify

something central to Keats’s progress. Although it ostensibly honours Burns, the sonnet

clarifies what Keats needs to poetically confront: reality—brief human reality—that

necessarily holds both beauty and suffering in the face of more lasting forms. All is cold

Beauty,

he writes; pain is never done.

Nature is long; art is long; life is

short. Keats is unsettled by what he feels—he also cannot quite understand why Burns

did not

somehow poetically engage the surrounding landscape. Keats will later profitably engage

this

problem more fully in some of his great odes in 1819, in which he will articulate

and explore

the power of art and nature as reflections upon and representations of knowing, consciousness,

and imagination—and in view of human mortality. Burns’s fame, as well as his hurried,

intense,

and heroically ambiguous life, does, then, challenge Keats’s view of the poetical

character.

That this sonnet is stylistically uncluttered with few tonal prettifications also

anticipates

new levels of accomplishment.

The journey into Scotland—this whiskey country,

he calls it (letters, 2

July)—continues west after leaving Dumfries. After passing through AuchKeats and Brown head toward Kirkcudbright and Portpatrick,

making their way through a few villages. While they enjoy some natural beauty, they

are also

often confronted with poverty (wretched Cottages, where smoke has no outlet but by the

door

[2 July])* and wildly varying lodgings and food (dirty bacon, dirtier eggs, and

dirtiest Potatoes,

[5 July]).

On 3 July, Keats and Brown breakfast at the tiny village of Authencairn. Later in the day, in a letter to his sister Fanny, Keats includes a short ballad that, on the surface, both memorializes and sentimentalizes a homeless old woman of the heath: Old Meg she was a gipsey. The poem’s inspiration is drawn from the human landscape that Keats is witnessing, but the subject—old Meg Merrilies, a gypsy—is nominally lifted from the very successful 1815 novel, Guy Mannering, which Brown much later tells us Keats had not read (like the other Waverly novels, it was originally published anonymously by Walter Scott). Keats, though, likely heard about the character from accounts of the book as well as its popular cultural figuring via a London stage adaptation over December 1817 into early 1818. However, Keats’s figure, given her intimacy with the landscape’s simple boon, derives something more from the naturalized sublimity of Wordsworth than from Scott’s somewhat supernatural (and somewhat meddling) gypsy. Keats’s poem would not have looked out of place among Wordsworth’s in Lyrical Ballads. The poem’s accomplishment is decent and subtle: its styled understatement perhaps anticipates another short ballad to come in April 1819, the more powerfully allusive La Belle Dame sans Merci.

Keats is also strongly put off by what he sees as the church’s tyrannical hold over the poor, which is even apparent in the cultural ambiance. They take in a few sites—ruins, abbeys, castles—but Keats is generally not impressed, though he notes some beautiful areas around Kirkcudbright. Two things are constant at this point: he is always hungry and tired. And he’s rapidly falling deeply out of favor with the flavour of oatcake.

In that letter to Fanny (written 2, 3, and 5

July), Keats also manages to write some personal, playful, and punchy doggerel, which

he

describes as a song about myself

(There was a naughty boy). In the

poem, he pictures himself as a poetry-scribbling naughty Boy,

armed with knapsack,

books, clothes, towels, hair bush, inkstand, and pen, intent on following his nose

To the

North / To the North.

But a portion of the poem also fondly captures his busy childhood

days and a warm reference to his grandmother (granny-good

), Alice Jennings.

From Portpatrick, a very brief trip (6-8 July) is made to northern Ireland and to

Belfast via

a mail-boat. Their hope was to speak with the Paddies

and to see Giant’s Causeway on

the north coast, with its wonderful connection with Gaelic mythology. On their walk

to

Donaghadee, they pass through a large Peat-Bog,

where they see dirty creatures and a

few strong men cutting or carting peat,

and they also pass through a most wretched

suburb

(letters, 9 July). At the time, a large portion of the population live in mud

cabins with clay floors, many with just one room and without any windows—and often

shared with

livestock; disease, like typhus, is rampant, and so would consumption. Keats finds

the poverty

more striking than what they have just seen in Scotland. What a tremendous difficulty is

the improvement of the condition of such people,

he writes; with me it is absolute

despair.

Most memorable for Keats, though, is the sight of a squalid, half-starved,

pipe-smoking, ape-like old woman, squatting in something resembling a dilapidated

doghouse,

and carried about on two old poles by two ragged girls—the Duchess of Dunghill,

he

names her. The trip into Ireland, then, is a fail: the poverty, the high costs relative

to

Scotland, and the landscape cause Brown and Keats to basically turn around, and the

Irish

adventure amounts to not much more than a botched and disappointing day-trip.

Perhaps at this point, Keats feels a little homesick or nostalgic. Perhaps, too, he

is

waiting for some moment of genuine inspiration, though the trip does not immediately

raise

much in the way of deeply creative moments. Why? There’s the obvious: they are constantly

on

the move, with a packed itinerary; always in sight-seeing mode; usually very tired;

sometimes

hungry; most of the time dirty. Time-wise, as he admits to brother Tom, Keats has not been able to keep up

his journal and

letter writing, which he feels is a commitment (3 July). So, too, in the back of Keats’s

mind,

are surely thoughts that he has, in a way, deserted dear brother Tom, who has been

very

ill—consumptive, clearly—at least since the beginning of the year. That is the reality

of what

he will have to return to.

[See here for an interactive, annotated map with a time line of Keats’s Northern Walking Tour with Charles Brown.]