20 January 1817: Dinner with Horace Smith, Expanding Connections, & Toward the 1817 Collection

No. 3 Knightsbridge Terrace (the island

), London

Keats, aged twenty-one, dines at Horace Smith’s* residence. Smith, a stockbroker, also writes some popular work for newspapers and a few journals, including verse parodies. Present are Leigh Hunt (celebrity publisher, poet, journalist, critic), Percy Shelley (young, brilliant, eccentric—and, at times, vegetarian—poet), and Benjamin Robert Haydon (well-known painter of historical subjects and defender of the Elgin Marbles). Keats probably first meets Smith at Hunt’s in December 1816.

This kind of company—a fairly impressive lineup—certainly expands Keats’s social,

intellectual, and literary circle. And no doubt such varied, eccentric, and experienced

company greatly challenges his ideas on just about everything, though in relatively

little

time Keats’s desire for independence and original thinking begins to show. In this

case, it is

a very lively dinner, with touchy discussions on various topics. Haydon records how Shelley (about three years older than Keats) opens one part of the evening’s

conversation with, As to that detestable religion, the Christian . . .

. It takes a

while for the baited comment to raise argument, but it initially seems to come from

Haydon,

who is a mainstream believer. Hunt is also up for a

little Christianity bashing. For his part, Keats seems to have been quiet on the subject,

which at this point paints a picture him mainly as an observer—he does, however, have

thoughts

about the subject, inasmuch as in a sonnet written a few weeks earlier—Vulgar

Superstition—he views religion and the religious mind as closely bound / In

some black spell.

But Keats could not have been quiet or passive all the time, since

those he met between October 1816 and, say, March 1817, were almost always convinced

of his

genius or great potential, and his company was clearly sought out.

In a way, an evening like this rivals the so-called immortal dinner

(see entry 28 December 1817), in that, as suggested, Keats would have soaked

up the knowledge and extraordinary opinions exchanged between Haydon, Hunt, and

Shelley in particular, thus forcing and

teasing out his own thoughts on various subjects—and on various individuals.

At this point in his career as a newly-declared poet, Keats, then, is greatly enthused by his growing circle of friends and acquaintances, most of whom are channeled though Hunt. And it is Hunt who, toward the end of 1816, encourages Keats to start thinking about gathering a collection of his poems to be published by one of Hunt’s friends, Charles Ollier, and Charles’ brother, James. The Ollier brothers, though, are anything but experienced: at this point they have not published anything, and have not officially formed themselves as a book publishing outfit. Their name: C. & J. Ollier, 3, Welbeck Street, Cavendish Square. The printer of the volume, Charles Richards (who ran his business from Warwick Street, Golden Square) also had a connection to Hunt through his brother, Thomas, who sometimes wrote for Hunt’s Examiner.

While on a walk together, Shelley advises Keats

against publishing youthful verses, but Keats goes ahead. Keats, a few years later,

and in an

exchange of letters with Shelley (and having a good-natured dig at Shelley for publishing

his

own early work), will refer to his 1817 collection as my first-blights

(16 Aug

1820).

This collection (Poems, by John Keats) will be put together for printing in short order (Keats brother, Tom, helped to make good copies of his poems for the press), and Keats will have to come up with funds to subsidize the cost of publication. Given that at this point in his writing career Keats is almost unknown, covering publication costs would not be that unusual, and it is doubtful that the Olliers had much capital, or were willing to take a chance on a novice poet. At best, they hoped that commission on sales will turn them a modest profit; it does not—sales are, alas (but predictably) dismal. A material copy of Poems does, especially in layout, show inexperience on the part of the Olliers as well as Keats.

The poems in the collection (thirty-one in total, including seventeen sonnets and

three

epistles) mainly display an inconsistent and striving young poet in search of a subject,

a

voice, and a style. There is not much in the line of expansive thematics, elegance

of

phrasing, or enduring insights. There is just enough for Keats to learn from; more

importantly, there is much to leave behind. But at this point, Keats is thankful for

Hunt’s encouragement and support: he dedicates the

collection to Hunt, commemorated as a last-minute sonnet entitled To Leigh Hunt, Esq. (The dedication to

Hunt is fitting, given that Hunt, between May 1816 and early 1817, has published Keats

on four

occasions.) The poem, a little oddly, pays more homage to William Wordsworth in the first two lines, before trundling

its way through nymphs, violets, the shrine of Flora,

and A leafy luxury

(perfect Huntian phrasing) before expressing the hope that his poems—poor offerings,

he

calls them—will please Hunt.

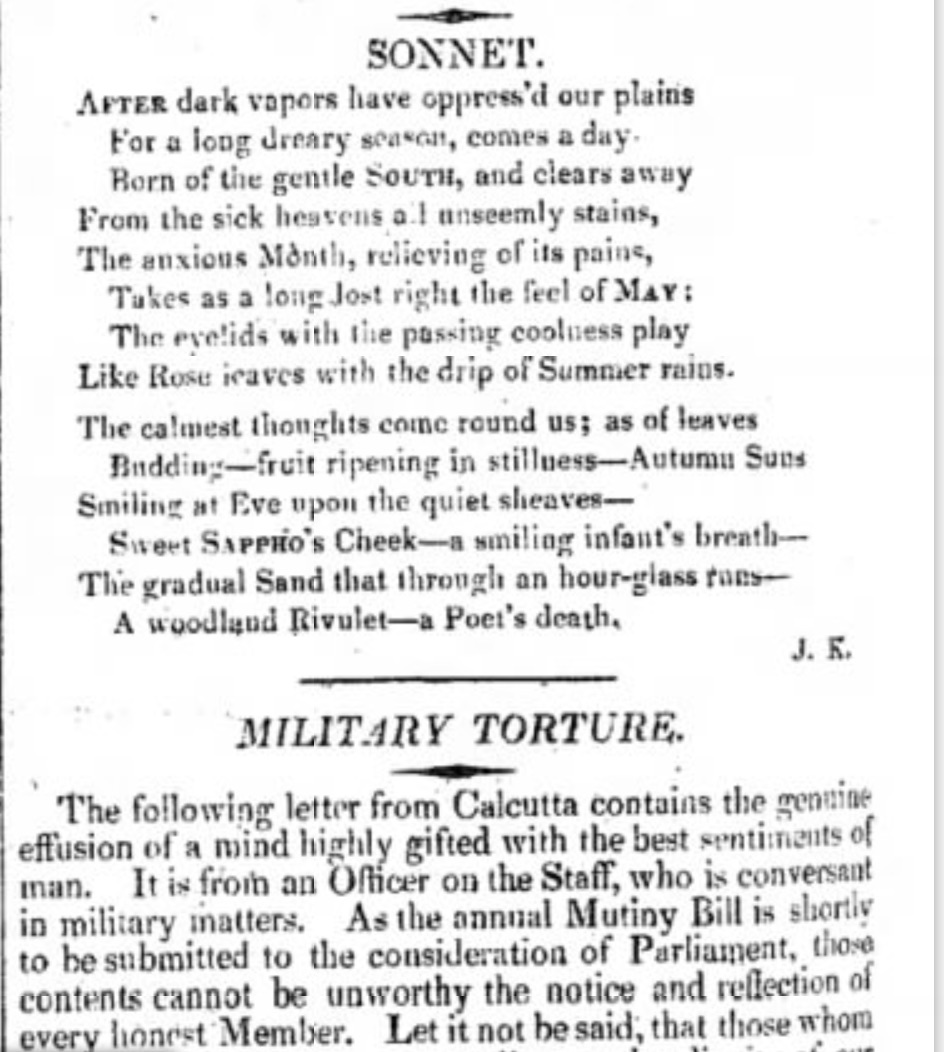

Keats also writes a mainly indifferent sonnet at this time—After dark vapours have

oppressed our plains. But, in its expression of hope for dark oppression to be

replaced by calm thoughts, one part of its imagery and thinking does look forward

to arguably

Keats’s greatest poem, written more than two-and-a-half years later, To Autumn. In the earlier poem, Keats

invokes fruit ripening in stillness

and autumn suns / Smiling at eve upon the quiet

sheaves,

phrasing that would not be tonally out of place in the later poem. After dark

vapours have oppressed our plains is published in Hunt’s

Examiner, 23 February, signed J. K.

.

Behind all of this, though, lurks the linking of Keats with Hunt’s political views (of liberty, free-thinking, and reform); in not too long, and in some conservative quarters, this will overshadow Keats’s poetic progress. Keats is no doubt aware that his now very public affiliation with Hunt will rankle some, and in particular, Tory reviewers, who are sharpening their pens in order to cut up Hunt—and now, too, his eager apprentice.

It is not fully clear if at this time in early 1817 Keats is still putting in some time as a medical dresser, though not too much after March 1817 we can be more certain he was not. It would have least brought in some much needed money, since, from October 1816 onwards, he seems to be living on credit (based on family inheritance), and he will be until about mid-1819. After that point it appears credit is gone—and probably most of the capital. He and his surviving brother, George, did not know that family funds (about 800 pounds, via his maternal grandfather) were available to them in Chancery. For the most part, Keats will have to live much of the last year or so of his life propped by the generosity of friends.

*Smith is perhaps best remembered as taking part in a sonnet-writing competition with Shelley; the result is an extraordinarily banal poem by Smith and an extraordinarily accomplished and dramatic poem by Shelley, Ozymandias.