25 July 1819: Shanklin, Fanny Brawne, & A Brighter Word than Bright

Eglantine Cottage, Shanklin, Isle of Wight

Keats is at the Isle of Wight with his very good friend, the supportive and witty James Rice, who in fact initiates the trip and invites Keats. Keats likes and admires Rice as an exceptionally good and sensible person. They arrive the end of June and take a small room in the village of Shanklin at a lodging-house, but at least with a partial sea view.

From the island, in a series of letters to Fanny Brawne over July and into August, 23-year-old Keats openly expresses great longing, passion, and unequaled love for Fanny. There is a sense that Keats is even a little surprised about how besotted he is with Fanny; from his perspective, he wonders what she sees in him.

Keats writes to his sweet Girl

(15 July) of her beauty, her lips, her eyes; of how his

heart is full of her, how he is absorbed

by her, and how he aches to be with her.

Echoing a little of Shakespeare , he writes,

I know not how to express my devotion to so fair a form: I want a brighter word than

bright, a fairer word than fair

(1 July). But all is not so clear: what evolves into the

first half of 1820 is that one side of Keats desires to be free from thoughts and

feelings

about Fanny, yet this is deeply conflicted by how

he wants to see her and how he imagines her. So while Keats’s deepening illness imprisons

him

into 1820, so do thoughts of Fanny, which is expected, given Keats’s waning hope for

recovery.

From the beginning, though, Keats is confused, even confounded, by Fanny’s personality,

and

particularly what he perceives as her somewhat flirtatious manner—Keats’s uneven jealousy

emerges quite early. Some of Keats’s friends are also clearly, and openly, not so

keen on

Fanny. She is also aware of this, which further complicates their relationship.

Keats does not feel perfectly well for much of July. He may have caught a cold or

infection

on the way to the island via Portsmouth as he passes through a storm and unseasonably

cold

weather; as usual, it manifests itself in his chronically-vulnerable throat, something

that

Keats himself notes (letters, 6 July) and that can be traced back about a year earlier

while

on his northern walking expedition into Scotland. Rice is himself very ill during the month; this, Keats says, weighs upon me day

and night

(letters, 31 July); it probably forces recollections of nursing his younger

brother Tom as Tom slid toward death in the

last months of 1818. Although Keats finds the area pleasant, he seems to require something

more from the landscape, something more large and overpowering

to fully impress him (31

July). He is beginning to feel a sense of idleness

So, too, are concerning portions of Keats’s energies taken up with financial anxieties relative to family funds. After Tom’s death in December 1818, these funds are necessarily shuffled and made even more uncertain; and now his brother, who has emigrated to America, is also going through serious financial difficulties. Keats is left to negotiate most of this through the trustee of the funds, the often-unaccommodating Richard Abbey. Remarkably, Keats is unaware that he has access to fairly significant family funds (mind you, Abbey himself seems unaware of these funds, which were established for Keats and his siblings by his maternal grandfather); Keats has, more or less, been living off ever-diminishing credit for a few years.

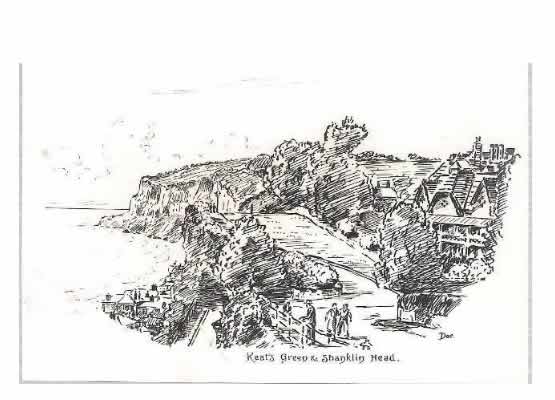

Keats Green & Shanklin Head.The cliff-top promenade (known earlier as Cliff-green or the Cliff Green, and part of a larger section known as Thorn Beds) was, in 1898, officially given the name

Keats Greenby the local district council, although name plaques were not added until 1910. The suggestion seems to have come via Arthur Patchett Martin. It will become a place for concerts and events. My thanks to the Shanklin & District History Society for this documentation.

Keats’s ostensible purpose on the Isle of Wight is (as he writes to his sister) to try the fortune of my Pen once more, and indeed I

have some confidence in my success

(6 July). Keats here refers to a play he is

co-writing with his very good and extremely generous friend, Charles Brown—titled Otho the Great. That is, he hopes to

make some money from the staged tragedy, write an innovative play, and recover something

of

his reputation as a writer. Keats, though, begins to feel the play might be becoming

somewhat

bogged down: about a week before he leaves the island, and as he writes to Fanny in the middle of working on a scene, he sees her through

the mist of Plots speeches, counterplots and counter speeches—The Lover is madder

than I

am

(5/6 Aug). Keats is right, though Regency theatre-goers are not unaccustomed to

convoluted melodrama. Keats also works on the first part of Lamia, a poem aimed to deliberately stir and attract readers’ attentions; he leaves

off the poem until late August; it is published in Keats’s last collection, the 1820

volume.

If none of these efforts succeed, Keats once more says he may fall back upon his medical

qualifications to support himself.

Brown arrives toward the end of the third week of July with his friend, John Martin (a publisher); they can at least get four people into the small room to play a little cards to pass the time; a few days later, Martin and Rice leave 25 July, and Brown and Keats work hard on the play. Otho the Great is accepted by the end of the year for production in the following theatre season, but Keats and Brown, perhaps too eager for success (and Keats too anxious for cash), withdraw it; they try another theatre, and it is rejected. The play then lingers and fades. Clearly they should have taken the first offer.

On that evening of 25 July, after a day mainly taken up with working on Lamia, Keats writes another

letter to Fanny. Keats’s manages to hit the

dramatic—or maybe melodramatic—in his passions: [H]ow I ache to be with you: how I would

die for one hour [. . .] I have two luxuries to brood over in my walks, your Loveliness

and

the hour of my death

(25 July).

Keats perhaps writes his Shakespearean sonnet, Bright Star, during

this month, since the letters to her contain many celestial references, and his feelings

for

her are couched in terms of constancy and intensity. (October 1819 is also a possible

time of

composition.) There may be hints in his imagistic thinking when, in a letter to Fanny, 1 July, he looks for a brighter word than

bright

to express his devotion to so fair a form.

In the same vein, Keats ends

the 25 July letter with, I will imagine you Venus tonight and pray, pray, pray to your star

like a Heathen. / Your’s ever, fair Star / John Keats.

The sonnet is uncluttered and

accomplished, and strikes the right tone of deep yet dignified passion. By any standard,

it is

strong poem that uses the established trope of a steadfast heavenly body, only to

both adopt

and trump that quality to suit and accent the speaker’s more unique condition. (A

very bright

comet that was making the news in the first week of July that Keats saw, and it may

also have

inspired the poem’s idea.) However, when we read the sonnet with Keats/Fanny in mind,

we fall

more heavily upon the conditional and personal anguish that ends the poem—or else swoon to

death.

As with much of Keats’s poetry, it ends by looking forward, to positing a

conditional future, to what might come.

Keats will make a copy of Bright Star on his way to Naples, October 1820. He will write transcribe it into his copy of Shakespeare, across the page from Shakespeare’s A Lover’s Complaint. [See 13 September 1820 for an image of the transcription.]

Keats and Brown will leave Shanklin 12 August, on their way north to Winchester: as the crow flies, this is about 48 km (30 miles); as the boat/carriage goes, this is about 80 km (50 miles).