1 July 1819: To Wight to Write: In Shanklin: Harnessed to a Dog-Cart & Entrammelled by Fanny Brawne

Eglantine Cottage, Shanklin, Isle of Wight

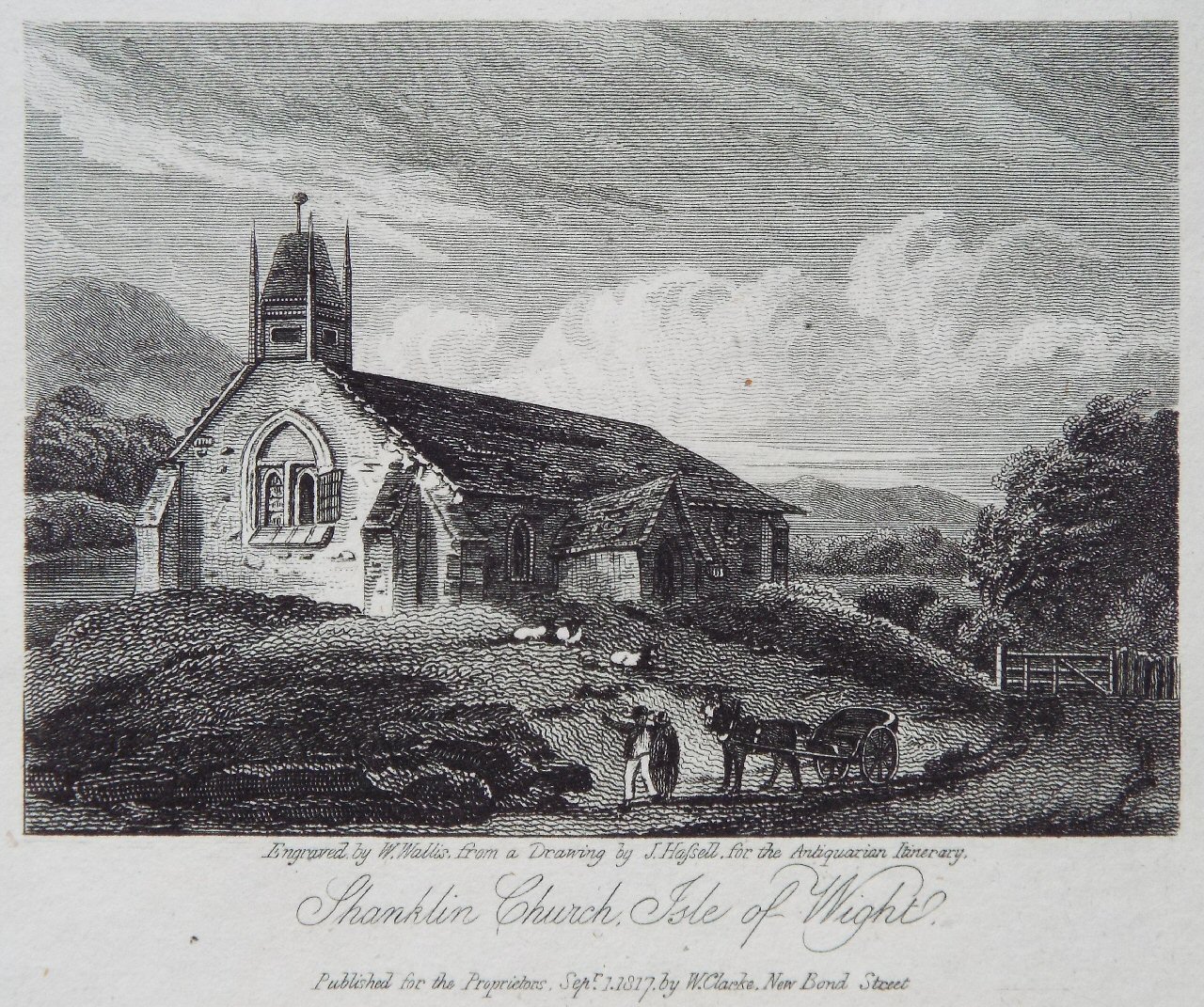

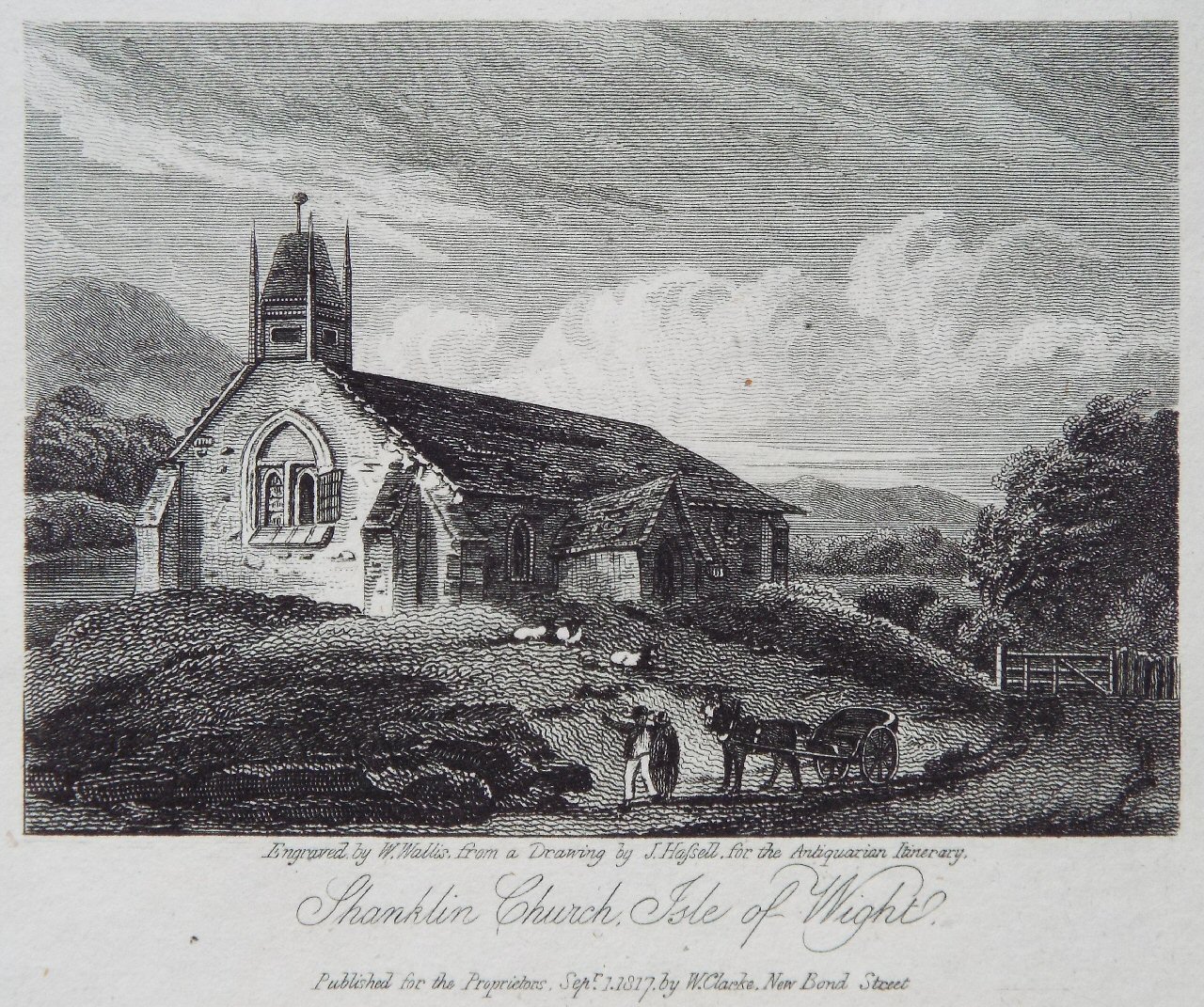

After a June in which Keats, aged twenty-three, struggles terribly with financial matters, and with having to find less expensive places to stay—and also a place where he might get some writing done and avoid his London circle—Keats travels to the Isle of Wight. He arrives 28 June in the seaside village of Shanklin (population about 150); he stays at a lodging-house—Eglantine Cottage—run by a older lady, Mrs. Williams. Keats is there with his dear friend James Rice, who for some time has been ill. They take a small room in the thatched structure; they have some distance sea views.

Here, over two years earlier, in April 1817, Keats spent about a week unsuccessfully attempting to get a good start on what would be his long and largely lackluster poem, Endymion, published spring 1818. Despite a few good passages, the project proves to be more an act of late-adolescent perseverance and wandering poetic enthusiasms than a sustained, brilliant display of early maturity, and Keats knows (and will say) as much. In fact, proofreading and revising it (beginning in early January 1818) was a good lesson—a key lesson, in fact—in what not to do again. But now, in the summer of 1819, his purposes are not to prove himself a poet, but to write for the sake of money, and he throws himself into purposefully into writing a play for the stage with his very close friend, Charles Brown. The title: Otho the Great. The plan: Brown will mainly supply the plot in prose outline; Keats, the actual wording—the versifying. By the second week of July, a first act of the play is complete.

Because of Rice’s poor health, Keats says he is rather a melancholy companion

(letters, 8 July). By the end of July, Keats confesses that I cannot bear a sick person in

a House especially alone—it weighs upon me day and night

(letters, 31 July). The

situation likely triggers the agonizing closing months of 1818, when he spent nursing

his

dying brother, Tom. Travelling via Portsmouth

through terrible rain, Keats also arrives with the return of his chronic sore throat,

which

may be a precursor sign of more lingering and dangerous health issues; a chill and

throat

stick with him for a couple of weeks. And Keats not only has his own finances to worry

about,

but also those of his brother, George, who is in

America. [For more on Keats and his throat issues, see 3 February

1820.]

Again, Keats hopes that his new writing will generate poetic and dramatic success—and

some

much-needed cash. Alignment with the truly immortal is not necessarily foremost in

his

thoughts at this point. He is there, he writes to his sister on 6 October, to try the

fortune of my Pen once more,

though if he fails, he can, he wryly says, always return to

my gallipots,

which alludes to the fully brutal treatment he receives from Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in August 1818, in which the

reviewer mockingly pleads Keats to ditch his lame poetic aspirations for a respectable

career

in medicine.

Writing to his friend John Hamilton Reynolds,

he seems somewhat surprised at how diligent

he is in getting on with the play he is

writing with Brown, as well in completing the

first 400 lines of the Lamia

poem (11 July), which he hopes might also generate some popular interest. Keats, however,

remains uncertain about success

at any level. But, at least personally, he feels

grounded and realistic: he can now, he writes, look upon the affairs of the world with a

healthy deliberation.

Whether this is a maturing of his poetic goals, or a new pragmatic

Keats, it is hard to tell, but he does describe himself as being in a less high-flying

and

fluttery state. With a nice touch of bemusement he writes, The first time I sat down to

write, I could scarcely believe in the necessity of so doing. It struck me as a great

oddity

(11 July).

now being pulled down to make way for modern improvements.Another local paper in 1898 mentions that the original cottage had been earlier

demolished.In 1910, Shanklin-born builder Francis Cooper (1837-1919) is reported to say that, some years previously, he

pulled down the old cottage where Keats had lodged.How much—if any—of the old structure is incorporated into the existing building is uncertain (for more, see here). My thanks to the Shanklin & District History Society in pointing to information about the cottage.

In a few letters from Shanklin, in July and into early August, we begin to get some

sense of

Keats’s complex relationship with and love for 18-year-old Fanny Brawne. He writes to her at least four times during July,

beginning the morning of first day of the month: The morning is the only proper time for me

to write to a beautiful Girl whom I love so much.

No matter what else he experiences,

her loveliness remains with him—her love, he tells her, has entrammelled

him, and so

destroyed my freedom

; he aches to be with her; until he met her, he never knew of or

believed in such love. He wants her to confess her love in a letter that will

intoxicate

him. In the context of telling her that he tries to write some poetry

every day, he says, I love you the more in that I believe you have liked me for my own sake

and for nothing else,

and he gets quasi-philosophical about Pleasure

and what he

repeatedly calls her Beauty

; he confesses that he finds himself kissing her writing (8

July) and that, like a heathen, he will imagine her as Venus and pray to her (25 June).

He

tells her that she utterly absorbs him. We find, though, that, with a little time,

Keats shies

away from full commitment. So, too, is he prone to jealousy, even without there being

anything

definite or rational to be jealous of; and he is also driven by his own poetic pursuits,

which

demands solitude for study and composition. Of course his unstable finances and health

complicate and counterbalance his commitment to Fanny. One side of Keats is determined

to

maintain his personal freedoms.

Keats, in a letter of 15 July, does express to Fanny his plan, though uncertain, to put together and publish a volume of his later

work, perhaps by year-end. He is cynical, though, about the state of publishing poetry

and

public tastes: Poems are as common as newspapers and I do not see why it is a greater crime

in me than in another to let the verses of an half-fledged brain tumble into the

reading-rooms and drawing room windows

(?15 July). However undirected this protest, it

does suggest that Keats feels he already has or will have enough for a decent volume.

How

right he is! Despite his glib yet resentful tone, Keats has earlier said that he won’t

publish

unless he is certain of its worthiness.

With his friend John Martin (a publisher), Keats’s playwriting partner Brown will arrive in Shanklin about the third week of July. The four of them—Rice, Keats, Brown, Martin—will cram themselves into the small room for a few evenings of card-playing, but not long after Rice and Martin leave. Keats and Brown need to get on with their play. But Keats also returns to his Hyperion poem once more, though now he will begin to revise it in the form we know as The Fall of Hyperion. This return signals that Keats has not given up on serious poetry—poetry for its enduring and dignifying qualities, rather than for the sake of the public, his purse, or sociable occasion. In a way, Keats’s Hyperion projects represent his attempt to come to terms with Milton’s considerable powers and influence. In about two months, Keats will give up on it again, though its considerable literary merits display, at least for us, Keats’s new level of poetic maturity and control. In sum: With The Fall of Hyperion, Keats has Milton and enduring poetry in mind; with Otho, Keats has the fashionable Regency theatre-going audience in mind.

Meanwhile, until about the third week of August, he and Brown will be, as Keats writes,

pretty well harnessed again to our dog-cart

—that is, to writing Otho the Great (31 July). Brown is impressed by how rapidly Keats

follows his plotting as plows into and through the story, even though Keats has no

idea where

the play is going. Plot-wise and character-wise, the play—a kind of mishmashed Elizabethan

royal family tragedy, with wayward love, betrayal, and of course death—offers both

too much

and too little: it is over theatrical and under developed, with a smattering of random

literary borrowings. Keats is somewhat concerned that too much of melodramatic might

seep into

the play. But given the tastes of those Regency theatre-goers, this might not put

it out of

the running for some modest success. On the more serious side, perhaps the best bits

of Otho offer some reflection that challenge notions of the public and

the private. [For more on the play, see 11 October 1819.]

Keats leaves Shanklin toward the end of the second week of August. Besides trying

to get some

work done on what will be a dead-end play, he has at moments enjoyed the sea-views,

watching

boats sail by, hills (Steephill, in particular*), dales, woods, sands, cliffs, rocks,

walks

(he mentions Bonchurch twice**), the romantic cottages, and, it seems, eating lobster.

And of

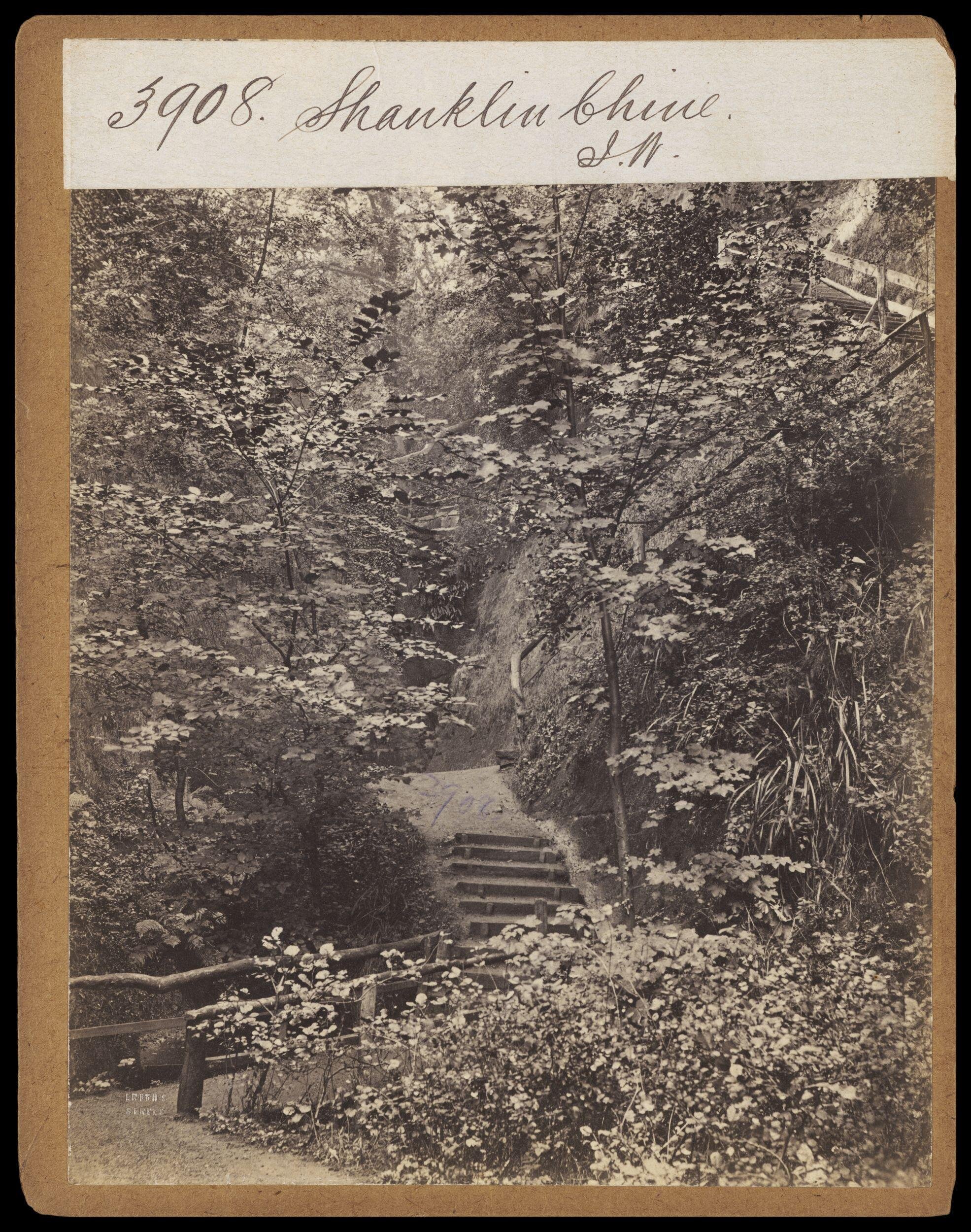

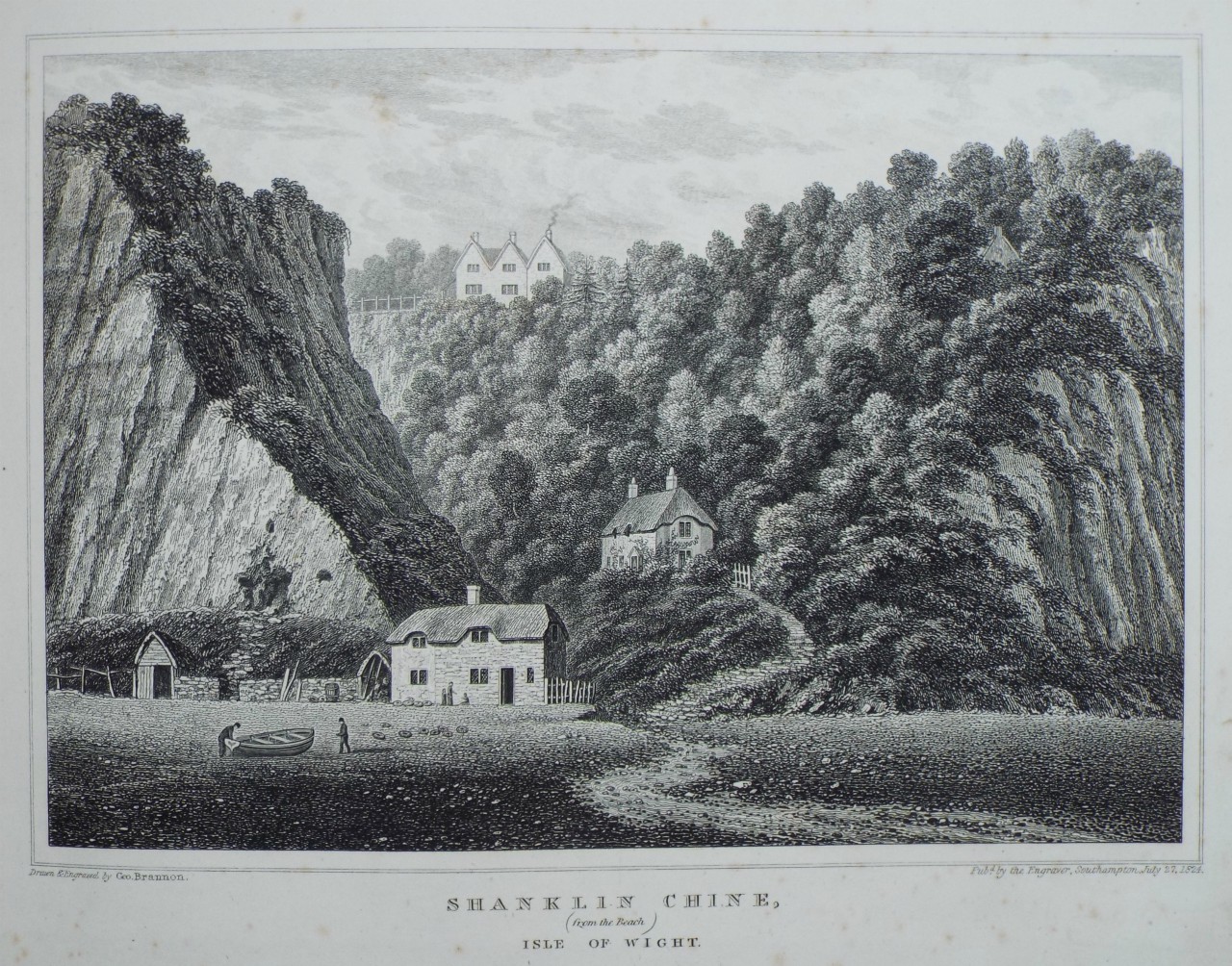

course Shanklin Chine*** (meaning a deep, narrow, sandstone ravine) is the most immediate

striking landscape feature (the path up the Chine was first excavated just in 1817).

But by

the end of July he says that he prefers very large and overpowering

landscape rather

than the picturesque,

which, it seems to Keats, is what many Isle of Wight tourists

seek—it is a popular destination, where visitors can enjoy the scenery and also, by

bathing,

take advantage of the sea’s advertised medicinal, curative powers. Keats with some

humor

describes the island’s visitors as hunting after the picturesque like beagles.

The

island increasingly becomes premier place for what is sometimes called picturesque

tourism.

So by the first week of August, Keats writes to Fanny that he will be happy to leave

Shanklin for Winchester, where he will welcome the cathedral and libraries (there

actually may

not be any)—and where it will take less time for their love letters to cross each

other (5,6

August). What also waits for him in Winchester is the unforeseen moment to compose

perhaps his

greatest poem, To

Autumn, which can be seen as the culminating point of his poetic progress. [For

more on To Autumn,

see 19 September 1819.]