23 June 1820: Keats Coming Full Circle: Under Hunt’s Care

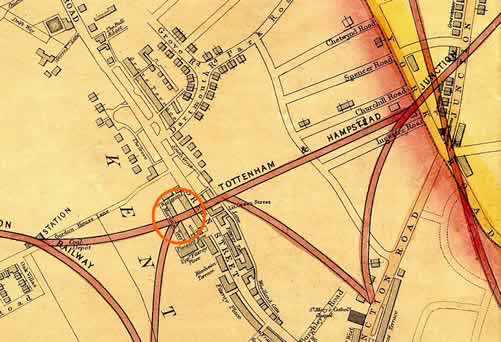

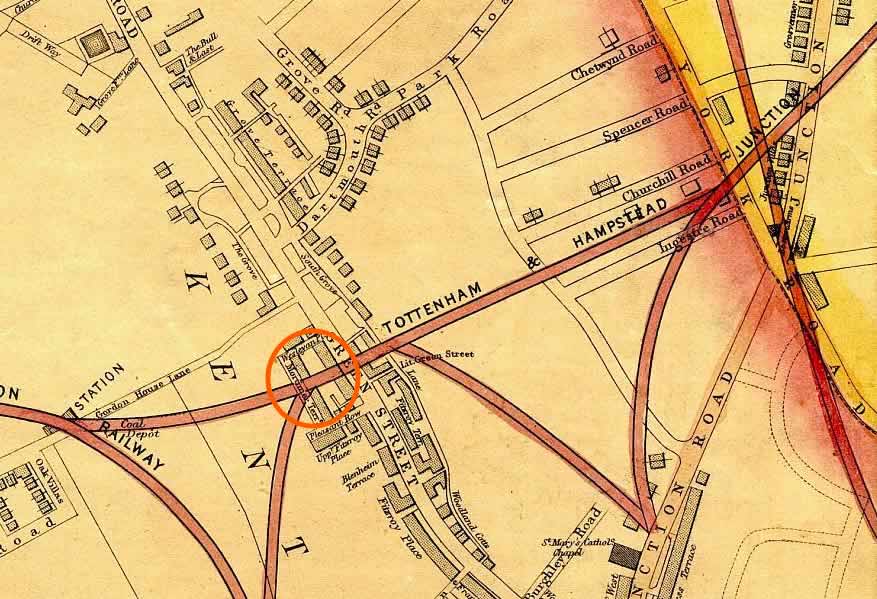

Mortimer Terrace and Wesleyan Place, Kentish Town

After about seven weeks at Wesleyan Place in Kentish Town, on 22 June twenty-four-year-old Keats coughs up blood—hemoptysis. The next day he is taken into Leigh Hunt’s home at 13 Mortimer Terrace (more or less around the corner) to have his precarious health monitored. The gesture of the Hunts’ is especially generous, since Leigh Hunt is himself quite ill at the time. Keats experiences more hemorrhaging during June.

Keats first spits up blood earlier in the year, on 3 February, at which time he feels it is a sure sign of his demise—consumption: the so-called white plague. He has been dealing with a fairly serious chronic sore throat for some time, perhaps set off by an exhausting walking tour, August 1818, which he cuts short due to illness; the throat and coughing issues may be a precursor sign of or predisposition to consumption; it is an illness known to wax and wane. His recent difficulties now clearly signal the accumulating movement of the horrible, lingering illness, given that his symptoms have moved to his lungs. [For much more on Keats and consumption, see 3 February 1820.]

Consumption (tuberculosis) previously took his mother; his younger brother, Tom; and it will later take his other younger brother, George. It was the largest killer of the age.

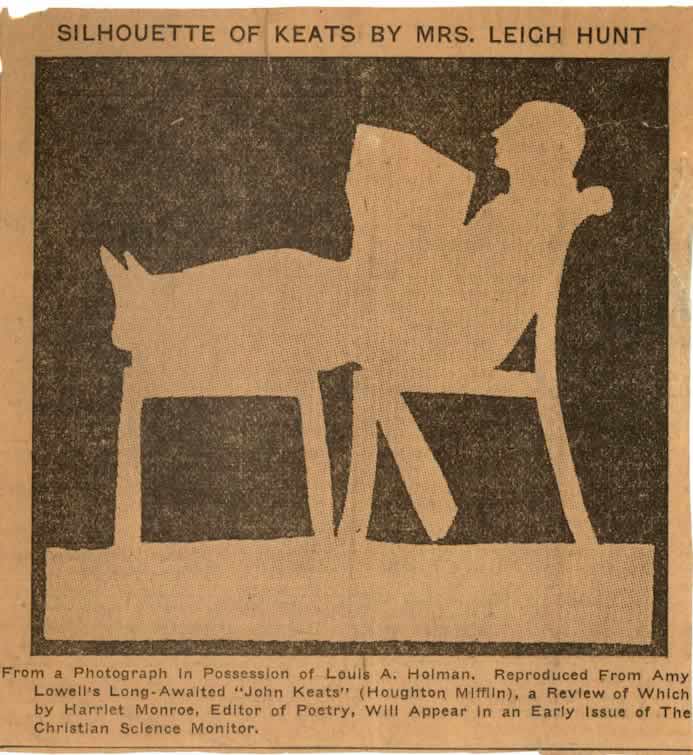

Keats meets Hunt in October 1816, though Keats, perhaps as early as about 1814, already views Hunt as a kind of hero for his independent, progressive voice (Keats would have been hearing about Hunt through his first significant mentor, Charles Cowden Clarke). Back in 1816 and into 1817, Hunt generously (and immediately) promotes and mentors Keats by tutoring his tastes, publishing some of his poetry, and, crucially, by introducing him into a certain social and generally liberal intellectual network revolving around Regency London. However, Keats’s enthusiasm with Hunt begins to wane relatively early in 1817, as Keats begins a two-year course to articulate his own poetics and to self-consciously develop an independent and original poetic voice. Keats comes to see that association with Hunt and Hunt’s style of poetry does, in certain vocal reviewing circles (mainly Tory circles, that is), open him up to political, poetical, and personal attacks, as well as to ridicule. But even more favorable reviews of Keats’s early work notes, often with some disparagement, Hunt’s poetic influence on Keats. What then irks Keats is that he had come to be seen as Hunt’s disciple and devotee. In an important way, Keats’s progress is tied to writing himself away from association with the kind of poetry written and valued by Hunt, though his generally quiet political sympathies remain in the same progressive and reformist camps as Hunt’s crowd. Keats, then, comes full circle by coming under Hunt’s care in June 1820. [For more on complexity of Hunt/Keats relationship, see the end of the entry for 6 March 1818.]

Keats is now fearful enough for his health that, at the last moment, he backs out of an invitation to dine with an impressive group that includes his friend Benjamin Robert Haydon (the historical painter), as well as Charles Lamb (poet, writer, essayist), Henry Crabb Robinson (journalist, reviewer, solicitor, diarist) and two of the age’s most esteemed poets, William Wordsworth and Robert Southey. Given that Keats is by far the junior member and least known of this group, and yet he is even invited to such a gathering, tantalizingly points to his personal qualities and, quite likely, some recognition of his potential.

Keats remains in contact with his betrothed, Fanny

Brawne (just about to turn twenty), mainly through notes to her. He is upset that

some of his friends mock her, but, to Fanny, he dismisses them as those laughers.

He

assures his fairest, my delicious, my angel Fanny

that his love for her is true: I

wish to believe in immortality,

he writes to her during the month; I wish to live

with you for ever.

But in truth, Keats does obsess over her in ways that reveal Keats’s

fears and deteriorating health. Loss, helplessness, panic, and longing are a terrible

mix.

During the last half of the month, and just after he makes some corrections on his

final

collection, Lamia, Isabella,

The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, Keats experiences a further significant

bout of spitting blood. Again, this does not bode well, despite a contrary and extremely

dubious medical diagnosis that there is nothing material to fear

(letters, 23 June). He

is given advice that going to Italy might help him recover his health. Attempting

to look

forward to something—anything—Keats vaguely believes he might himself return to a

medical

career (having qualified in 1816) if his last effort at publishing fails. At the same

time, he

sees himself turning increasingly away from the world, despite great kindnesses that

have been

shown to him (to Charles Brown, ?21 June). But

behind all this lurks the obvious: the mycobacterium tuberculosis bacillus is usually

an insistent, deadly pathogen.

On the last day of the month, Keats sees advance copies of his new collection. He

says he has

low hopes

for it (letters, ?21 June). Despite a couple of weaker poems, the

collection is in fact astonishing, and it rivals the best collections in the English

canon.

Keats, though, is miffed about the inclusion of Hyperion, a

strong but unfinished Miltonically-inflected poem that his editors decided, against

his will,

to include. The publishers, Taylor & Hessey, will introduce the volume with an

Advertisement claiming that Keats did not complete Hyperion

because he was discouraged

by the harsh critical treatment that his previous volume,

Endymion (1818),

received. Keats, in an 1820 volume that he possesses, at some point puts a line through

the

Advertisement and writes at the head of it that he had no part in [writing] this

; but

what they claim about Endymion upsets him even more: beneath it he writes, This is a lie!

Three things worth noting: first, that the construction of Keats as the weakened victim

of

cruel reviewers could be said to begin here; second, that such a construction doesn’t

start

with Keats; and third, behind this, that Keats very upset by the suggestion about

having a

lack of fortitude.

But throughout the final months of 1820 and further, there will be many positive reviews for Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems. What is of course sorrowful is that critical praise comes to poor Keats as he rapidly falls to consumption and hopelessness.