20 December 1819: Without the Poetry of 1819 . . .

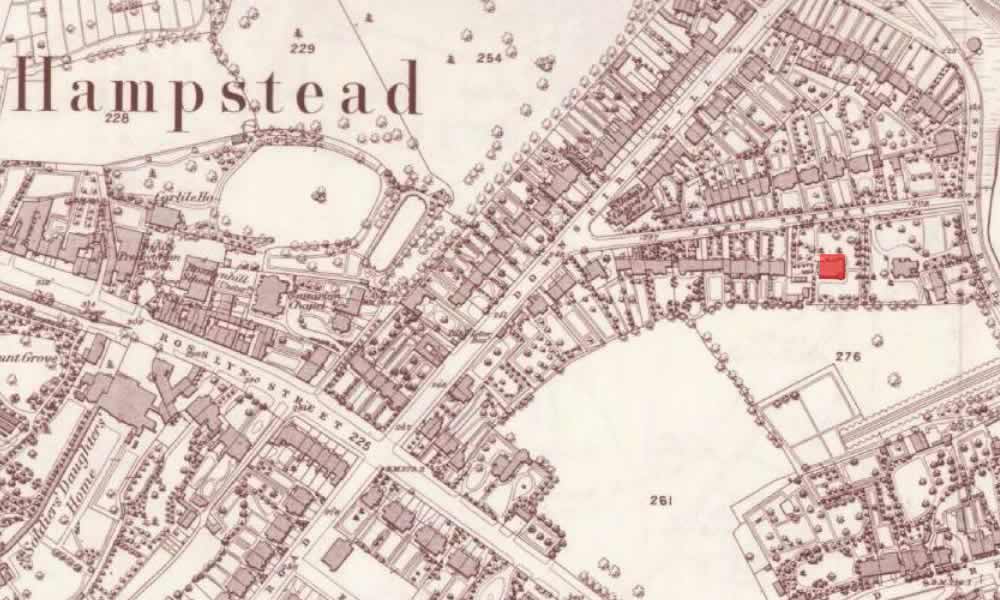

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

Where Keats, twenty-four years old, has lived since the second half of October. He first rents part of the double-house a year before, having been invited by his very close friend, Charles Brown, after the death of his younger brother, Tom, 1 December 1818. Between then and now, Keats has stayed in a few other places (notably, Shanklin and Winchester), and during this period of something less than a year, he writes almost all of his best poetry, much of which ends up in his third book, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and Other Poems, published June 1820 by Taylor & Hessey. Keats prepares at least some of the volume for publication during December, even though the previous month he tells his publisher that he does not want to publish his recent work. It looks like many of the editorial decisions were out of Keats’s hands.

Keats’s chronic sore throat surfaces once again during the month. As he writes to

his younger

sister, Fanny, on 20 December, my throat [. .

.] on exertion or cold continually threatens me,

and his doctor advises him to get shoes

and a coat that will protect him. Two days later he writes to her again—a shabby note,

he calls it—in order to apologize for his uncertain plans: I am sorry to say I have been

and continue rather unwell, and therefore shall not be able to promise certainly.

Keats’s throat problem haunts and plagues him, and is most pronounced during August 1818-March 1819, though it resurfaces at earlier points in 1819. These may be indications of a predisposition to or even lingering signs of consumption (tuberculosis—TB), of which he is very much aware, and at moments makes him dreadfully fear cold weather and exertion. His family history—being a witness to the deaths of both his younger brother and mother from the illness—gives these fears some credence. Keats’s other younger brother, George, also dies of consumption in 1841, aged forty-four. Having said this, consumption is the pervasive contagious illness of the era (though not understood until later in the century as contagious), and Keats could have contracted it just about anywhere at any time. (The TB bacilli is passed through the air or in dust, where it can survive up to six months; someone can also be infected, though full symptoms can take years to develop.)

In the 20 December letter to Fanny, Keats

expresses financial and reputational expectations for a play, Otho the

Great, which he co-wrote with Brown

mainly in the summer, with some recent minor revisions: My hopes of success in the literary

world are better than ever,

he writes. How wrong he is—at least in the short term.

Despite genuine interest from Drury Lane Theatre, and with some vague signs that the

premier

English actor of the moment, Edmund Kean, might

feature in it, their impatience to have it staged quickly causes them to pull back

the tragedy

and offer it to Covent Garden Theatre, which perfunctorily rejects it. Thus Otho the Great comes to nothing, which is not surprising since its

dramatic and literary merits are modest and blandly derivative. This is really the

last blow

to Keats’s possible writing career.

Keats writes little if any new poetry after late 1819. His poetic progress up until this point is, quite naturally, the product of complex and often interconnected factors, including, of course, his own inherent and unique capacities and personal history, which are infinitely complicated and never fully knowable.* How do we account for and measure the extraordinary variability in and the shaping of anyone’s personality and abilities? How, in Keats’s case, do we, for example, account for his truly uncommon sympathetic imagination, or the paradoxical grace of his awkwardness?

Without the poetry of 1819, his last year of writing, Keats, at best, would have become a romanticized and tragic figure of poetic potential, and, at worst, a marginal poet within a larger, more important circle of London Regency culture. He escapes both destinies for a larger one.

[*For a summary of these factors, see the concluding chapter.]