14 August 1819: All I Live For: Looking Upon Fine Phrases as a Lover; Otho, Not So Great

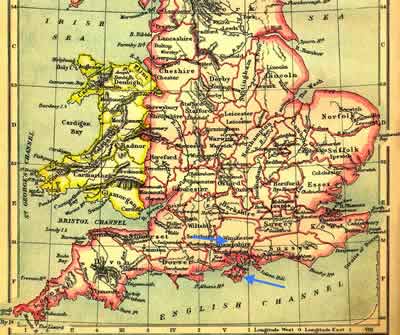

Isle of Wight to Winchester

Tiring of the Isle of Wight after about a six-week stay (where Keats refers to his

room on

the island as a little coffin

—letters, 16 Aug), Keats and his very good friend Charles Brown move to Winchester, departing 12 August.

Keats comes to enjoy Winchester’s ambiance and surroundings, especially the woods

and church,

not to mention the convenience of a Library

(letters, 14, 28 Aug). The dry, hot weather

seems to help with his health and temper—delightful,

he calls it: I adore fine

Weather as the greatest blessing I can have

(28 Aug). Cold, damp weather actually

reminds Keats of his own susceptibility to (and fears about) his chronic sore throat.

Keats and Brown work very deliberately on a play

together—Otho the Great, begun the end of the first week of

July—from which they are determined to achieve some financial success, and Keats some

recognition and very much needed cash. Brown supplies mainly plot notes, and Keats

finds the

wording and versification to link it all together. Keats’s further high-minded aim

is to

make a great revolution in modern dramatic writing

(letters, 14 Aug), though his

ambition in this instance is inflated by hope.

By the middle of August, a draft of play is just about completed. Mainly because of their impatience with getting the play staged (and mitigating circumstances within and between the production companies themselves), it never makes them a penny and is never produced in their lifetime. The play, a kind of Gothic-Elizabethan mash-up with a bit too much of the melodramatic, works decently enough relative to the quality of popular theatre at the time, but even with Keats’s gifts and Brown’s earlier minor success as a playwright, Otho is not so great. It will have to wait about 130 years to be staged, and then more for the sake of curiosity than dramatic worthiness.

But behind Keats’s determination for dramatic success are numerous troubling issues

and

circumstances: growing exhaustion; lingering health difficulties and worries about

how long

his constitution will hold out (letters, 24 Aug); acute financial stress set off by

complexities involving money from the family estate; the necessity of asking friends

for loans

and unreturned loans (Brown financially supports

Keats, but now feels stretched);* worries over future directions (poet? playwright?

journalist? medical practitioner?); and struggles with some of his own, more serious

work,

mainly the Hyperion story, but also finding direction for Lamia, which he hopes will have some popular appeal. Finally, there is his puzzling

relationship with and regard for his loved one, Fanny

Brawne—puzzling, that is, for Keats. After four openly passionate and longing letters

to Fanny in July, Keats continues to write to her in August, though by the middle

of the month

his feelings are, at least for the moment, somewhat tempered. He writes to her that

he has

been so busy—plunging so deeply into imaginary interests

—that he has not, thankfully,

idle leisure to brood

over her (16 Aug). He admits to her that his letter of 16

August is excessively unloverlike and ungallant.

Beginning to surface is Keats’s hate and contempt

for the literary world

(letters, 23 Aug). Just a few years ago, in late 1816, Keats entered this world with

bright-eyed expectations revolving around possibility and fame. But now he seems to

despise

all forms of public taste. As he tries to explain to his good friend and publisher

John Taylor, he greatly prefers the possession of

wings of independence

over gross popularity; in the spirit of self-awareness,

determination, and a little bravado, he believes that this Pride and egotism will enable me

to write finer things than any thing else could—so I will indulge it

(23 Aug).

As mentioned, Keats in August makes a return to and uncertain continuation of the Hyperion story with what we know as The Fall of Hyperion. He earlier tries the story in the fall of 1818, but abandons it by April 1819, though its promise is substantial. But even with this new beginning, in just over a month (and after over 500 lines), he once more gives up on the poem. Keats feels less confused about what he is trying to achieve (something like high, classic art), but how it is to be achieved, and how he might achieve it in a style and voice his own.

Directly behind these stylistic concerns is a self-conscious but deep engagement with

Milton’s grand accomplishment—twice during August Keats calls Paradise

Lost a wonder

—but Keats doubts that through such a Miltonically-inflected

style can he genuinely approximate the beautiful and give expression to sensations

that

correspond with his own imaginative capabilities and poetic character. Milton’s poetry, it turns out, may be a model to study—and study

it he does!—but less a model to exactly emulate. The extensive marginalia and markings

in

Keats’s copy of Paradise Lost are perhaps the best material

evidence we have that show Keats’s probing, intellectual engagement in attempting

to

critically parse the exact qualities of great poetry, and in particular, Milton’s

style.**

Keats is ever an astute student and critical reader of poetry.

Given that Keats this month works on Lamia, Otho the Great, his reconstituted Hyperion story, the fragment drama King Stephen, and revisions to The Eve of St Agnes—as well as a little mischievous ditty that includes a struggling fly spooned out of pot of milk—suggests that Keats’s writing energies are, at least temporarily, renewed.

Keats’s direct and weighed struggle to make some progress tells us much about his sophisticated critical challenge to develop his own poetical direction, which he initially achieves mainly in his spring 1819 odes, and anticipated by The Eve of St. Agnes and La Belle Dame Sans Merci. But Keats’s voice, style, and own form of accomplishment come more strongly than ever in just over a month, in the composition of, arguably, his best poem, To Autumn—a poem of quietly astonishing equipoise. This, again, tells us much about his development and the direction it seems to be taking.

Belief in the value of what he attempts to poetically achieve remains strong: he writes

to

his friend and sometimes guide, John Hamilton

Reynolds, I am convinced more and more day by day that fine writing is next to

fine doing the top thing in the world.

He he goes on to passionately argue and confess

that his uncertain state of striving profitably goes in one possible direction: it is the

only state for the best sort of Poetry—that is all I care for, all I live for

(24 Aug).

As he has progressed, then, Keats has striven to have unique poetic conversations with his great precursors; and he has hoped that his deeper subjects—mortality, consciousness, enduring art, the tensions between the imagination and knowledge, between the ideal and the real, between the material moment and the immaterial idea of time—will be enduring topics. His most steadied poetic articulation of this will come in just over a month.

* On the last day of August, one of Keats’s good friends, Richard Woodhouse, writes to another, Keats’s friend and

publisher, John Taylor. The ostensible reason

is to try find some financial support for Keats, but both are, as it were, experts

on

Keats’s poetic style and development. In Woodhouse’s letter we hear a touching and

convincing assessment of Keats’s progress, potential, and character. Woodhouse worries

that

Keats’s considerable superior & improving Powers,

even with his comparative

imperfectness,

should not be wasted on writing for the depraved taste of the

age

—he has Otho the Great in mind. Instead, with a

solitary spirit

and noble pride

akin to Milton, Keats should, if possible, be

understood and supported. This is high praise and touching sentiment, though Woodhouse

prides his assessment on objectivity. Woodhouse also touches on Keats’s declared goal:

to

write not for the age but for the ages.

** Beth Lau’s invaluable Keats’s Paradise Lost (1998) transcribes and offers critical commentary on Keats’s marginalia in his copy of PL. Based upon Lau’s work, Keats’s copy of PL has, in 2020, been shaped into an open-source digital edition ( Keats’s Paradise Lost: a Digital Edition), making it open to computational analysis.