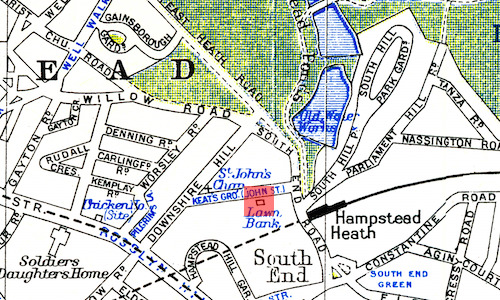

12 May 1819: Viewless Wings & the Complex Play of Consciousness & Imagination: Ode to a Nightingale

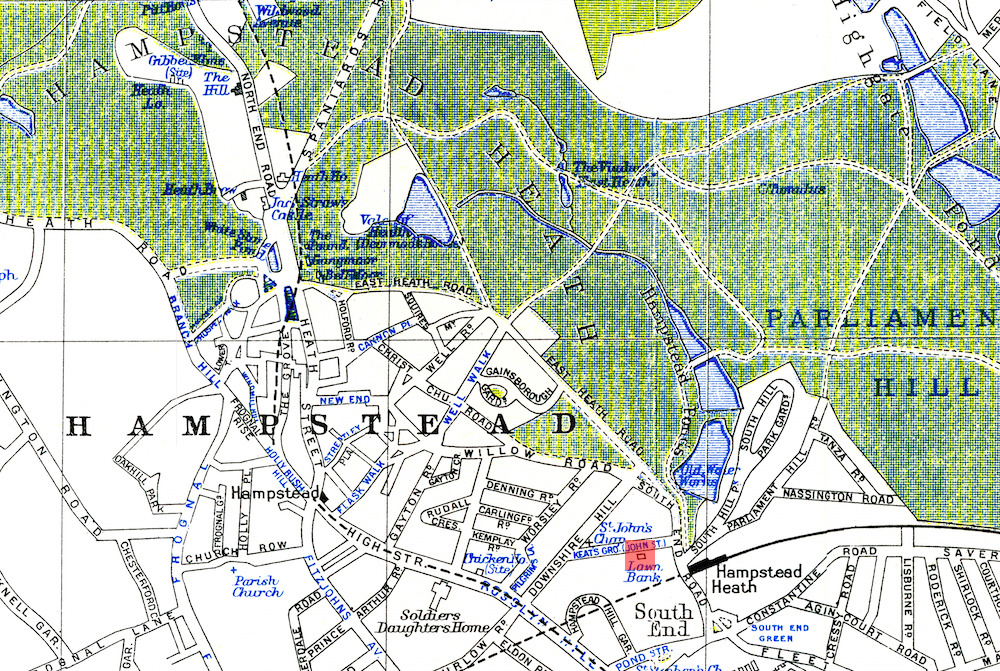

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

May 1819 seems to be a relatively slow month for Keats. It follows from the first

few months

of 1819 when, despite being quite socially active, he hopes that ambition or inspiration

will

raise him and save him from (what he variously calls) laziness, languor, indolence,

and ennui.

In May, Keats does manage to visit his younger sister, Fanny, a few times; he sees the guardian of the family estate over uncertain money

issues, which is usually unproductive and stressful, though this time the meeting

is civil; he

returns some borrowed books that he’s had for six months; he entertains becoming a

ship’s

surgeon, since a livelihood from writing seems an impossible dream (he drops the fanciful

medical idea in early June); and on 12 May he reports to Fanny that he has at last

received a

letter from their brother George, who, with his

wife, Georgiana, emigrated to America in June

1818, and they seem to be doing quite well.

For a period around the third week of May,

Keats is once more ill and confined.

But during May and its surrounding weeks, Keats composes poetry that centrally contributes

to

the reason he becomes a canonical and hugely influential poet: he writes the majority

of his

so-called great odes.

Though their dating is not fully certain, most can be centered in

this spring. One of them is his Ode to a Nightingale.

Charles Brown, who is Keats’s generous friend and

roommate at Wentworth Place, claims that Keats, one morning and while sitting under

a plum

tree, writes the nightingale ode after hearing the bird’s tranquil joy

near his house;

within a couple of hours, Keats has some scraps of paper

that he, Brown, rescues and

helps to arrange—these become the poem. Brown’s story (recalled almost twenty years

after the

poem’s composition) sounds a little aggrandizing and suspect in details, but it is

about all

we have to go on in terms of vaguely contextualizing the poem.

Perhaps also behind Keats’s attraction to the subject is the chance walking encounter

he has

with living-legend Samuel Taylor Coleridge

just a few weeks earlier, during which, for a few miles,

Coleridge in Coleridgean fashion astonishingly rambles on about just about

everything—including core subjects in Keats’s own poem-to-be: consciousness, sensations,

poetry, and nightingales. Keats was already familiar with Coleridge’s own conversational

poem

about the nightingale (1798/1817) that conjures nature’s immortality

(31), which in

turn calls upon Milton’s

Il Penseroso

(Milton also wrote a sonnet, O Nightingale

), and Coleridge’s poem

is always in the back of Keats’s literary mind. But to station the opening mood and

action of

his poem, Keats seems to call much further back than a few weeks, to a classical poet

with

whom he is greatly familiar: Horace, who in the opening lines of Epode xiv, writes

about

passive indolence and forgetfulness enveloping his inner senses, and then conjures

quenching a

parched throat by draining a cup of something that might bring on Lethean slumbers;*

this

passage obviously permeates Keats’s own opening. But the poetic trope of the poet/nightingale

is fully pervasive in the literary canon, so Keats very consciously—and profitably—joins

this

greater conversation.

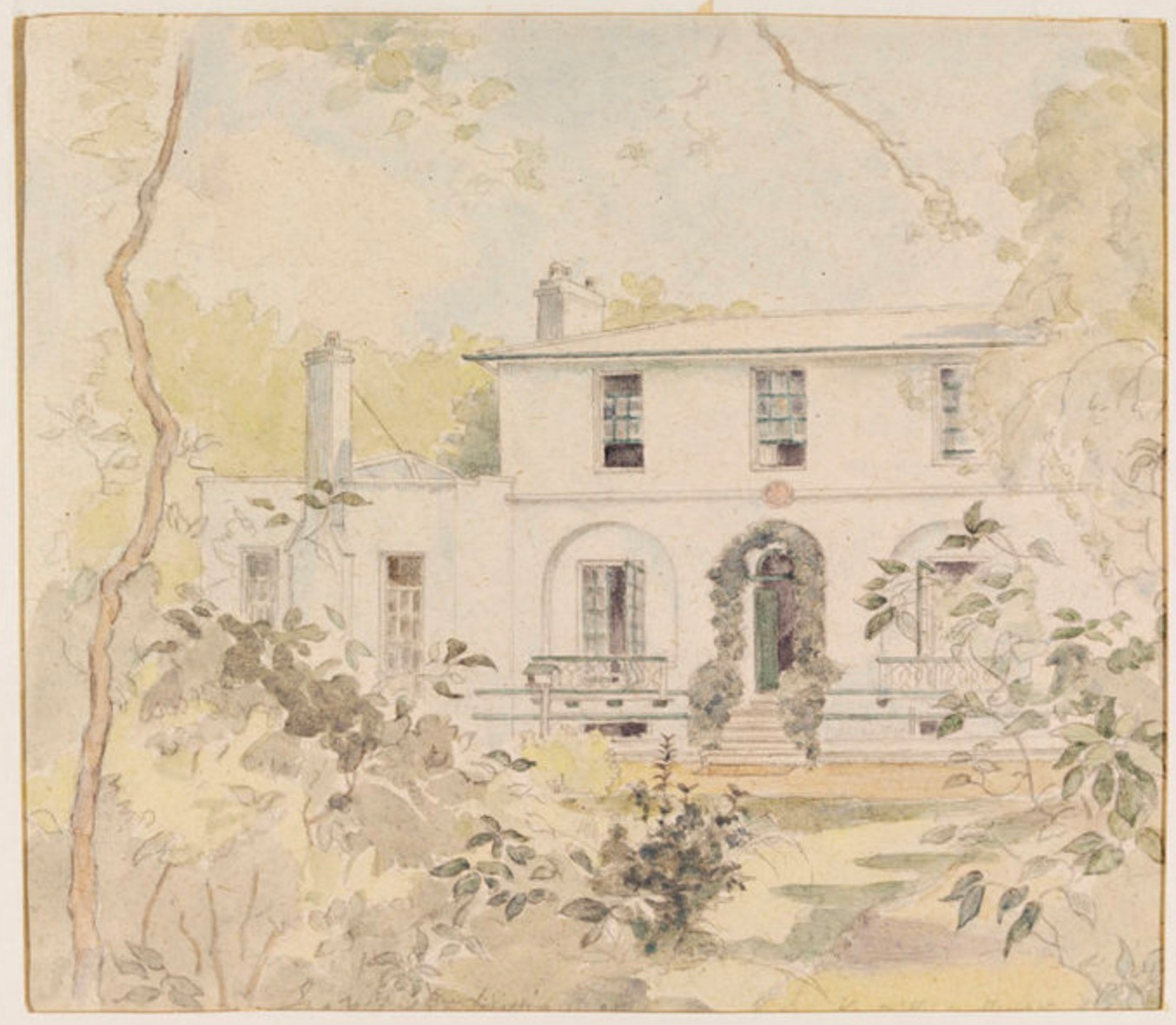

Listen to the song of the nightingale (only the male sings):

The poem startlingly marks Keats’s progress as a poet, in this, the final phase of his writing. So what does he write about, and how does he write it?

Most generally, Ode to

a Nightingale flies over and then lands into well-travelled poetic territory:

the meaning of human suffering and uncertain consciousness, with the seduction of

death in the

face of hopeful, but doubtful, transcendence. While the easefully singing nightingale

flies

from some kind of time-past, then to be buried deep

(77) in some kind time-forever, the

speaker is left in his darkening time-present with his own sole self

(72); in his

all-too-human moments of questioning, bewilderment, and fading beauty, he poetically

lingers

between and complicates states of consciousness and intoxication, pain and release,

anticipation and resignation, sleep and waking, dream and vision, desire and resignation,

darkness and insight—and between, of course, those thoughts of death and deathlessness.

As a

poet, the speaker’s recourse is to imaginatively be with or to follow the nightingale

though

the viewless wings of Poesy

(33). That is, poetry perhaps offers or represents some

form of lasting consolation beyond sorrow and pain, but, paradoxically, it also has

to capably

embrace mystery and doubt, which is fully central to Keats’s literary philosophy.

History

itself, looking for its own moments of meaning—the desire of those hungry generations

(62)—cannot hold the bird and its eternal song. Can it hold any certainty for the

listening

yet creative speaker—who, after all, has his perfectly controlled poem about an uncontrollable

subject that now holds us?

The remarkable poem enacts Keats’s newly-found tone of controlled, dramatic intensity. The speaker pushes up against his strong and uncertain emotions without fully giving into or resolving them, though part of the poem’s lyrical drama is the speaker’s ache to indeed give into them. That he cannot fully comprehend the state of his own narrower and numbed consciousness does not matter; that he cannot even clearly see the world around him as darkness encloses does not matter; that his imagination may itself be deceptive does not matter; these do not matter since the truth of the nightingale’s beautiful, enduring song provides thoughts and feelings deeper that his own place or moment, challenging his temporal, struggling consciousness. The poem’s accomplishment is that Keats makes certain that the speaker’s internal uncertainty does not fully spill over into excess or sentiment or cliché, and part of the poem’s power (once more, its complex drama) is how very close he comes to doing so as he listens in closing darkness, with intimations of immortality fused with the beauty of the nightingale’s fading song. On this level, then, the bird is at once an object of emulation, envy, and escape.

And so, in terms of Keats’s poetic progress, the ode returns to and extends Keats’s

oldest

subject: the desire to be an enduring poet—only now the voice in the poem is no longer

that of

a wannabe poet in search of a purposeful or potent subject. There is some excessive

phrasing

in the poem that recall his early poetry—like beaded bubbles

(17) and dewy wine

(49)—but Keats moves toward description, thoughts, and feelings uncluttered by poeticisms.

Now, instead of composing rambling, mawkish, and ineffectual verses about these longings

and

occasions that cater to it, here the poet’s desire is expressed not only with great

tonal and

formal control (the 10-line stanza is subtly innovative), but also with dramatic,

complex

intensity that invokes all the senses—and, moreover, it is expressed movingly. It

is, in an

important way, truly Shakespearean—in fact, the poet’s tone and language in attempting

to face

the meaning of life’s dark inconstancy sounds something like young Hamlet’s inner-dialogical

explorations of the same topic. Like Hamlet, all the ode’s speaker has is his eloquence

and

his sole self

(72); and, like Hamlet, Keats’s speaker is half in love with easeful

Death

(52) in conflating sleeping and dreaming. So, too, do both confront the meaning,

and morality, of human suffering; and, as in Hamlet, imagery of

darkness is utterly pervasive. It might, then, be useful to imagine the speaker of

Keats’s

poem as Hamlet himself, especially given that is not usual to think of young, inward-seeking

Hamlet as a poet representing a vision of darkness and profoundly articulate uncertainty.

But beyond the poem, there also, back into Keats’s world, there seems little doubt

that the

line about how youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies

(26) also holds for Keats

the image of his younger brother, Tom, dying

in his arms of the wasting disease, consumption. Also beyond the poem: That easeful,

untroubled throat of the bird could strike us beyond (or behind) the poem since, for

some

time, Keats has suffered from fairly severe throat issues, perhaps connected to lingering

consumption.

One of the ode’s strategies is to have the poet’s longings and potentiality transferred

to

the bird. This is fitting, since the nightingale, with its full-throated ease

(10),

assumes the role of an enduring poet of the kind to which Keats aspires: it flies

through or

transcends human fears, aspirations, suffering, death, and, as mentioned, even history.

Moreover, the bird’s song, though unknowable, is richly beautiful—full

—and therefore

truthful, even if the speaker’s state is closer to an emotional limbo. Another way

to express

this is to say that the mortal poet’s struggle is with the nightingale’s intimations

of

immortality; and his fleeting vision of that timeless bird that gives rise to a questioning

of

his own state couples with his desire for his own possible immortality as a poet.

Then there

is also the lurking but crucial question for the poet: How is the creative temper

to be

sustained?

To put this a slightly different way, the poet’s passing desire to establish this

identification with the Immortal bird

(61) is so that he can, as it were, fly to and

fade with it. Yet the paradox remains: the bird’s song surpasses or transcends the

truths

about waning beauty, human suffering, and death—and yet those are the subjects that

Keats

knows provide poetic depth that his new work of 1819 so profitably explores. One primary,

literal tension, then, is between the grounded, feeling poet in a world of suffering

and

fading beauty, and the flying, vanishing bird in the world of lasting ease—but, again,

this is

a tension the poet longs to collapse or appease by fading to or with the nightingale.

The

nightingale belongs to all time; the poet worries that he is tethered to his sole self

(72). Is imagination, is beauty, is poetry, is art (in this case, all troped by the

idea of

music), enough to see us through our human lot? Keats suggests these, in fact, are

all we

have. This is a large, lasting message. And though the nightingale is a somewhat hackneyed

subject, Keats’s handling is startlingly original. Keats understands that one goal

of great

art is to offer a new or even bold experience of an old subject, and this he has achieved

by

his desire to move with the bird out of and into history—and literary history as well,

given

that the poem at various moments channels Horace, the Old Testament, Milton, Shakespeare,

Wordsworth, and Coleridge.

The dramatic situation at the poem’s end, with the speaker brought back to his solitary,

disoriented reality while the beautiful and allusive bird seems to disappear into

a possible

dream-ideal of an historical past, brings back Keats’s earlier poem, La Belle Dame sans Merci,

written in April, and the poem that, along with The Eve of St. Agnes, signals Keats’s

period of greatest work. The ode does not quite give us the cold hill-side of the

waning,

woe-begone

Knight (6), but the speaker of Ode to a Nightingale likewise is

achingly allured by death, and is also caught between vision, sleep, and dream as

the bird

fades away Up the hill-side

and into the next valley (77-78). The Knight’s seductive

lady in the meads

(13) is not, then, unlike the speaker’s seductive nightingale: both

seem unreal, both invoke mourning or melancholia; and both sing in an alluring, unknowable

language that transcend the moment. Yet, despite this not-knowing, both poems go to

some

length to express how the songs of the bird and the dame are beautiful; thus they

articulate

and represent the core of Keats’s poetics that privileges intensity, doubt, and mystery

over

fact and reason

(letters, 21 Dec 1817). Both the lady and the bird are gone, and the

Knight and the speaker await, eternally forlorn, confused, and caught between dream

and

reality, vision and experience. To borrow syntax from the last line of the ode, fled

is the

music—likewise the belle dame and the nightingale. Both the ode’s speaker and the

knight are

left behind in the world of uncertainty, human suffering, and mortality, having sensually

encountered a beautiful yet ultimately unknowable ideal.

What we learn from the parallels between the two poems is a new range in Keats’s poetic

powers and in the consistency of his mature thematics. Once more, we have poems directed

toward a possible though uncertain future, and caught in the profitable poetic state

of

Keatsian in-betweenness. With Ode to a Nightingale, Keats

dramatically represents the eternal power of mystery and not-knowing. Both his song

and the

bird’s song are joined by resisting time and reduction. This is a recipe for one aspect

of

poetic greatness: the complex play of consciousness and imagination which the speaker

simultaneously creates and into which he is absorbed. This is also a general pattern

in the

other so-called great odes,

whether that absorption is into, for example, a Greek urn

or a season.

The ode is first published in Annals of the Fine Arts, July 1819, and subsequently in Keats’s third and final 1820 collection. It is the first of the five odes to appear in the volume, and the fourth poem overall. Ode on a Grecian Urn follows it, and The Eve of St. Agnes precedes it.

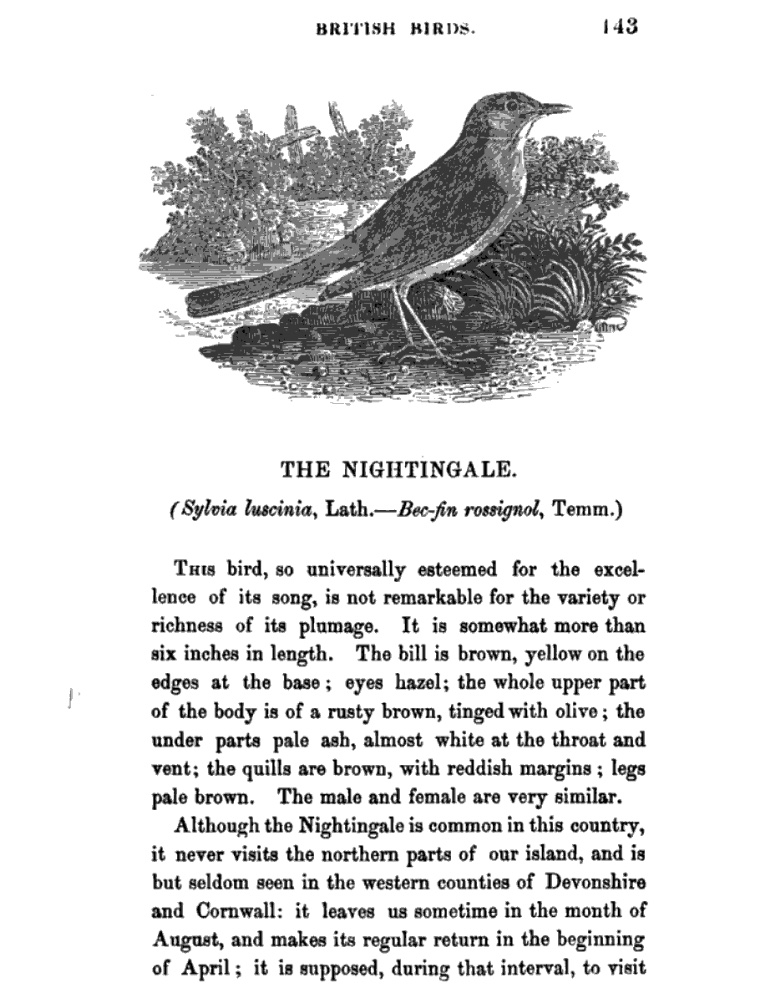

* A more direct translation of Horace’s Epode xiv:

“. . . you hurt me by asking so often / Why passive [soft] indolence [oblivion] has diffused [spread] / As profound a forgetfulness through my inmost senses as if / I had, with a thirsty throat quite parched, / Completely emptied the cup [bowl] that brings on Lethean slumbers.”

Ode to a Nightingale,

lines 1-4:

“My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains / My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk, / Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains / One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk.”