21 April 1819: La Belle Dame sans Merci & the Negatively-Capable Poet

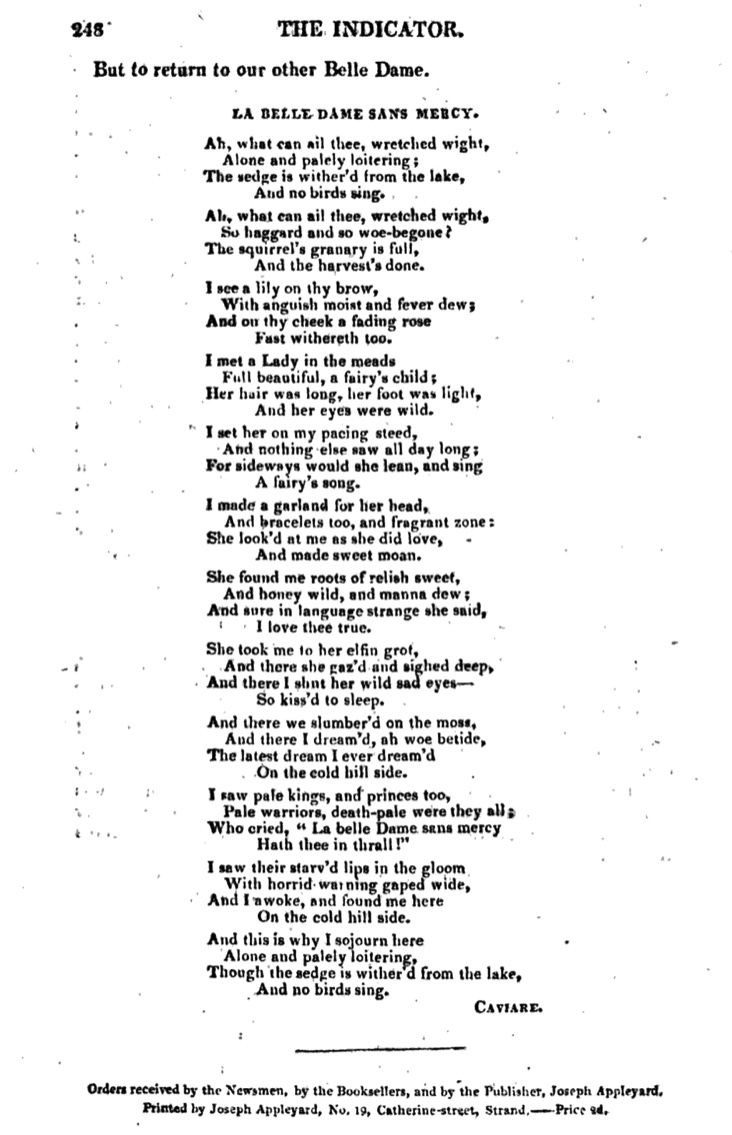

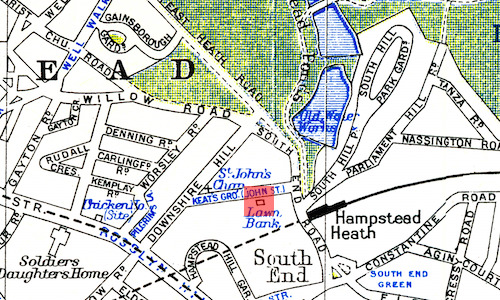

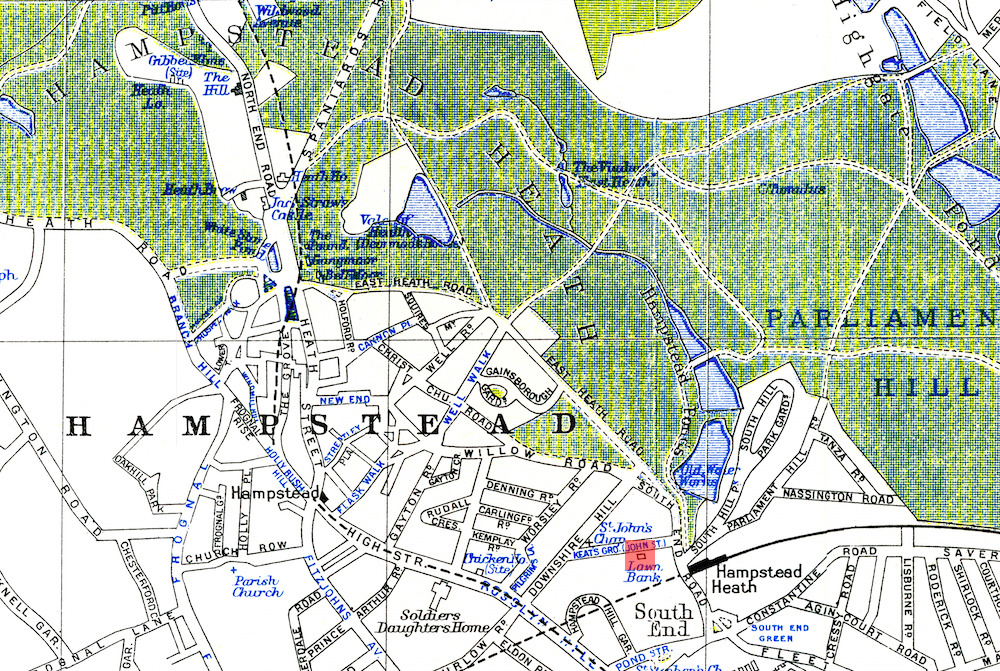

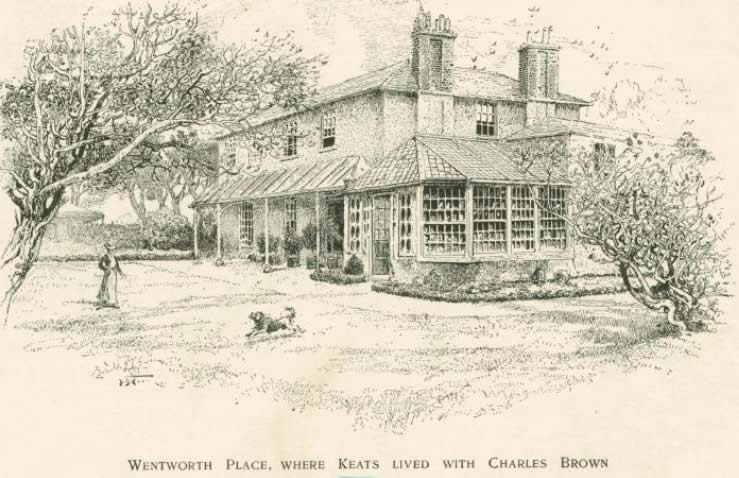

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

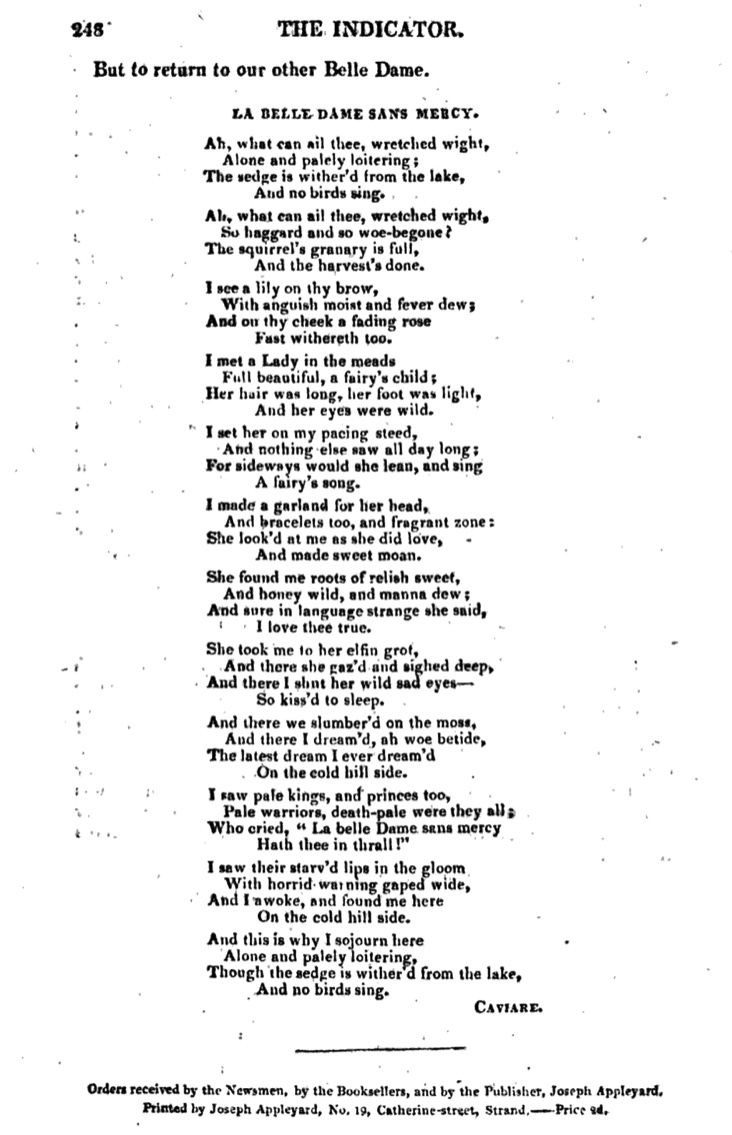

Keats composes the powerfully enigmatic La Belle Dame sans Merci around

the third or fourth week of April. He writes out a version of the ballad in a 21 April

letter

to his brother, George, and wife, Georgiana (who are in America). The poem is first

published in Leigh Hunt’s The Indicator, 10 May 1820

(without Keats’s name), but it does not appear in Keats’s 1820 collection, which is

both

unfortunate and surprising. The generally inferior Indicator

version of the poem has some variants that, compared to Keats’s letter draft of the

poem,

might suggest Hunt made some changes to the published text; in particular, the somewhat

gratuitous alliteration in the first and fifth lines of wretched wight

(rather than

knight-at-arms

) differs from the otherwise subtle sound sense in the poem. [See

bottom of page for The Indicator version.]

La Belle Dame sans

Merci is perhaps Keats’s first complete poem to fully enact a poetics he has

been developing since late 1817, when he begins to realize a few key things: that

occasional

poetry, the poetry of fancy, and poetry that privileges sociability, subjectivity

for its own

sake, and the desire to entertain do not embody or enact what he calls the poetical

character

(letters, 27 Oct 1818).

Keats’s defender, good friend, and close reader, Richard Woodhouse (who also may have had a hand in the Indicator version of La Belle Dame sans Merci), in

reflecting on Keats’s young but original genius,

writes that a Poet ought to write

for Posterity,

and not for the day, or rather the hour

(letters, 23 Oct 1818).

Woodhouse here tells us something important about Keats’s qualities and goals: to

create

timeless work, and timelessness in fact becomes a profound subject in some of his

final work.

Keats has been downplaying thoughts of fame and ambition in this, the last phase of

his poetic

development, though in his first phase as a poet he obsesses over poetic fame. How

will Keats,

in effect, write out of and beyond his own history and toward the future, to join

those

enduring, great voices of Posterity

? How will he not be a London, Cockney, or

Regency poet—the callow dilettante sitting at the feet of Leigh Hunt? Or, to fashion the question differently, how will he become more than

his own moment?

The answer in fact is clearly manifest in Keats’s poetry of 1819. The topics of those poems deliberately defy history and time while also uniquely probing the very human challenge to the idea of history and mortality. We can of course bind Keats and his poetry to the specifics of a time and place, in the same way we can place the most universal of poets, Shakespeare, into a time and place; but again, the conscious and then achieved goal of Keats’s greatest work is to place his poetry in larger, deeper, and more lasting conversation with his subjects—mortality, mutability, human passions, suffering, imagination, art, poetry, truth, beauty.

La Belle Dame sans

Merci takes on these subjects and more, and it finds its expansive power (and

those conversations) via complex allusions that take us through (to name a few) Edmund

Spenser (most obviously), Thomas the Rhymer, Alain

Chartier (at the very least the title), Petrarch, Robert Burton, Dante (Cary’s translation; Keats reads some Dante this month),

Chaucer, and Coleridge, as well as to that

long literary tradition of the deceptive enchantresses. Keats is also very conscious

of the

ballad tradition and what can be evoked within the ballad form. Then again, we could

in part

return some of the poem’s buried temperament to Keats’s own romantic circumstances

of early

1819, and in particular to his complex attraction to Fanny Brawne and what she represents (the relationship does leave him palely

loitering

); or perhaps the poem partly evokes Keats as a witness to the lingering

suffering and then fairly recent death of his younger brother, Tom, in December 1818.

The compressed metric form that Keats innovates functions to accent the starker aspects

of

the poem’s narrative. Yet the subtle though striking accomplishment of La Belle Dame sans Merci—its

strategy, in fact—is to place us, the readers, alongside the poem’s protagonist, that

palely loitering

knight: we are, together, both caught in an equipoised moment of

not-knowing. That is, within the drama of the bare, allusive narrative, and in the

guise of

allegorical romance, we are purposely placed within and between tensioned positions

of doubt

and indeterminacy in idea and imagery: between dream and reality, beauty and decay,

life and

death, myth and experience, desire and resignation, certainty and doubt, love and

loss,

passion and pathos, time and timelessness, silence and sound, sensuality and sterility—and

even between questioner and listener. The poem rests (sojourns

) without, it seems, any

irritable reaching-after or resolution: its only truth resides in its beauty and uncertainty,

like the belle dame herself. And though the poem’s questioner directly asks the knight

why he

is ailing, alone, sorrowful, and (it seems) dieing, the knight’s bare tale remains

both

evocative and irresolute. Temptingly, where imagination begins and ends is blurred;

and just

like Madeline in The Eve

of St Agnes, it is unclear if we have been hoodwinked by the meaning of

circumstance, which is paralled by the knight in his encounter with Lady in the Meads.

Perhaps most strikingly and subtly, then, the poem is an allegory of the Keatsian

poetic

position: the poet-knight is held, lingering between those indeterminant positions,

and that

is where he must, it seems, forever remain; he like a forever-fading figure on an

urn. Some of

this profitable uncertainty revolves around the word merci,

which carries the notion

that the belle dame has not granted something, but what is that: knowledge? sex?

understanding? We know that she has considerable power (she has the knight in thrall

),

but what exactly is that power? Now, if we know Keats strong ideas of poetry and art’s

greater

purpose, we might answer that her power is pleasure, which thus works with the poem’s

narrative, its allegory, and Keats’s theory of poetry.

That Keats stations the poet-knight within imagery of withering, wasting away, and

lingering—fevered, fading, and palely loitering

—also seems to capture the darker side

of indolence that Keats himself constantly faces, as well as once more enacting that

fatal

attraction of the ideal. The difference in terms of Keats’s progress? We find that

Keats now

profitably and profoundly uses what he knows, what he has felt and experienced, what

he has

studied, to position his poetry within greater and more enduring contexts. We are

not now (as

in too much of Keats’s early poetry) merely entertained by poeticisms, by something

sociably

clever, by something over-purposed as artful, or by (heaven help us) something immediately

relevant; we are now, in this poem, genuinely drawn in: to use Keats’s own measure

of artistic

merit, there is indeed something to be intense upon. Or, to borrow from Keats again,

the

imagery of the poem and the final station of the knight do, as in Ode on a Grecian Urn,

tease us out of thought

in order to teach us the only lesson that we need to know about

the deeper, potent, capable quality of the unknowable, that Beauty is truth, truth

beauty.

And finally, in keeping within the further explanatory power provided by Ode on a Grecian

Urn, we can see that the urn and knight are aligned: the knight has, with his

final positioning of stillness, quietude, and coldness, likewise become a foster-child of

silence and slow time

; in effect, he, like the urn, figures as a Cold Pastoral.

A

difference between the two poems is that Keats in La Belle Dame sans Merci

explores a darker slant of Negative Capability

—the poem, the knight, and the reader are

all caught, as it were, between enchantment and disillusion.

These contrasting dimensions and forms of profitable not-knowing—of, as suggested,

Negative Capability

—will also feature in Keats’s soon-to-be-written Ode on a Grecian

Urn,

Ode on

Melancholy, and Ode to a Nightingale. Keats’s

poetics are at last fully—poetically—enacted. And one more lesson: the best way to

read Keats

may be through Keats—that is, through his poetics and the very terms of his best poetry.

Keats’s thinking at this moment antipates the poetry he is about to write; we see

April 1819

as moment of complex and fairly intense speculation about matters of suffering, sorrow,

death,

salvation, and perfectibility. In his long journal letter to the George Keatses in

America,

his ideas revolve around what he calls The vale [or System] of Soul-making

: how

necessary a World of Pains and troubles is to school an Intelligence and make it a

soul

(letters, 21 April 1819). That is, this month (and in that letter) Keats now also

articulates

and accepts the idea that pain and suffering are essential components of our world

and human

nature, mainly centred by the human heart, a trope at least in part mined from the

depths of William Wordsworth’s phrasing and

thinking; the heart feeds all, teaches all, and is the medium through which all must

pass.

Though Keats is also a skeptical thinker, with most things in the world generally

reduced to

mutability and uncertainty, he strikes the belief that beyond this world of suffering,

the

identity of our souls does take on some larger purpose or meaning. To take this idea

over to

the narrative of Keats’s poetic progress, there is little in his early poetry that

explores or

represents anything like the necessity or deeper significance of a World of Pains

as it

crosses through consciousness. But now he sees it, and he is ready to explore this

in his

poetry. Keats will, for example, very soon articulate part of this larger realization

in a

poem that explores how desire and the senses fold into dark, uncertain consciousness;

he

writes, Where but to think is to be full of sorrows

(Ode to a Nightingale).

In the background, Keats now gives up on his larger poem, the Miltonic Hyperion, claiming, somewhat vaguely,

dissatisfaction with his poem. [Hyperion:

Book I; Hyperion: Book II; Hyperion: Book III.] It remains a

highly accomplished fragment—so accomplished, in fact, that, despite Keats’s wishes,

a

decision will be made by his publisher to place it in his final 1820 volume (as the

final

poem, no less). Keats is upset by this, and then by the publicly-announced reason

given for

publishing it (made in the Advertisement

to the volume), that nasty reception of his

Endymion was the

reason for the poem being abandoned. Keats, though, claims that he was simply too

sick at the

time to proceed with the poem, yet this, too, is perhaps not quite right. Looking

at the poem

closely, perhaps Keats did not know what larger ideas he hoped the poem might ultimately

express; in a related way, there are also unsettled characterizations and vague plot

lines

that, in the end, might have presented too much to overcome, despite his investment

in the

poem’s highly accomplished tonal and stylistic advances. A clear measure of Keats’s

progress:

Hyperion reads nothing like Endymion, which,

despite being an attempt to write an allegorical romance, has little that feels classically

lofty, little that feels naturally restrained, and much that feels plagued by a mired

plot as

well as jingling rhymes at what seem to be important moments—it is at the same time

overloaded

and random.

With La Belle Dame he moves toward the form of the lyric and lyric ode to gainfully enact his developed poetics of disinterestedness, intensity, and indeterminacy—poetry that also privileges sensation by suggestion rather than by explanation. There is imaginative conceptualization without narrative (or narrator) elaboration. There is stark yet brooding drama without any attempt at moralizing. With the poem Keats has learned much: less can be more.

And so April remains an important moment in Keats’s progress, despite quite a lot

of

socializing, getting tipsy at a claret feast

with a bunch of friends, being very angry

about a friend who had written fake love letters to his younger brother, Tom, having something of a low state of mind

during part

of the month, as well as experiencing some fatique (letters, 16 and 21 April). His

poetry is

about to make its most substantial jump.