14 March 1819: A Medical Future or Great Poetry? A Pivotal Keatsian Moment

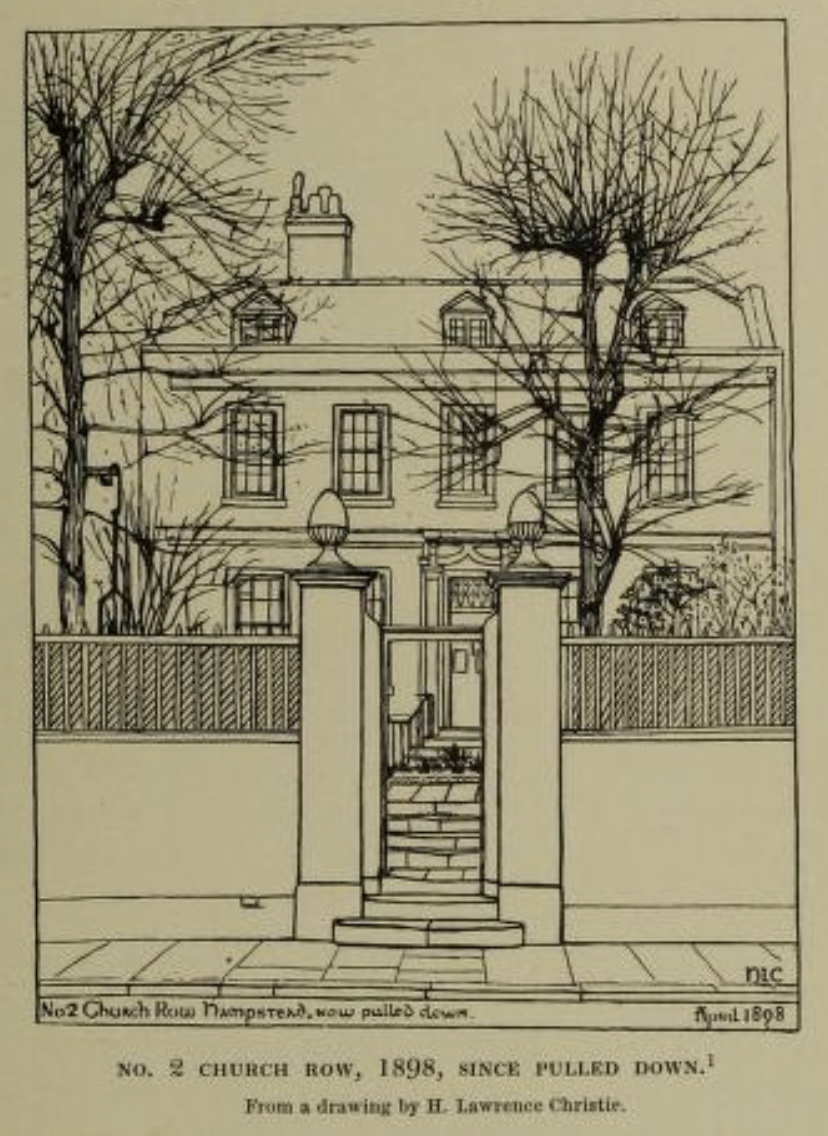

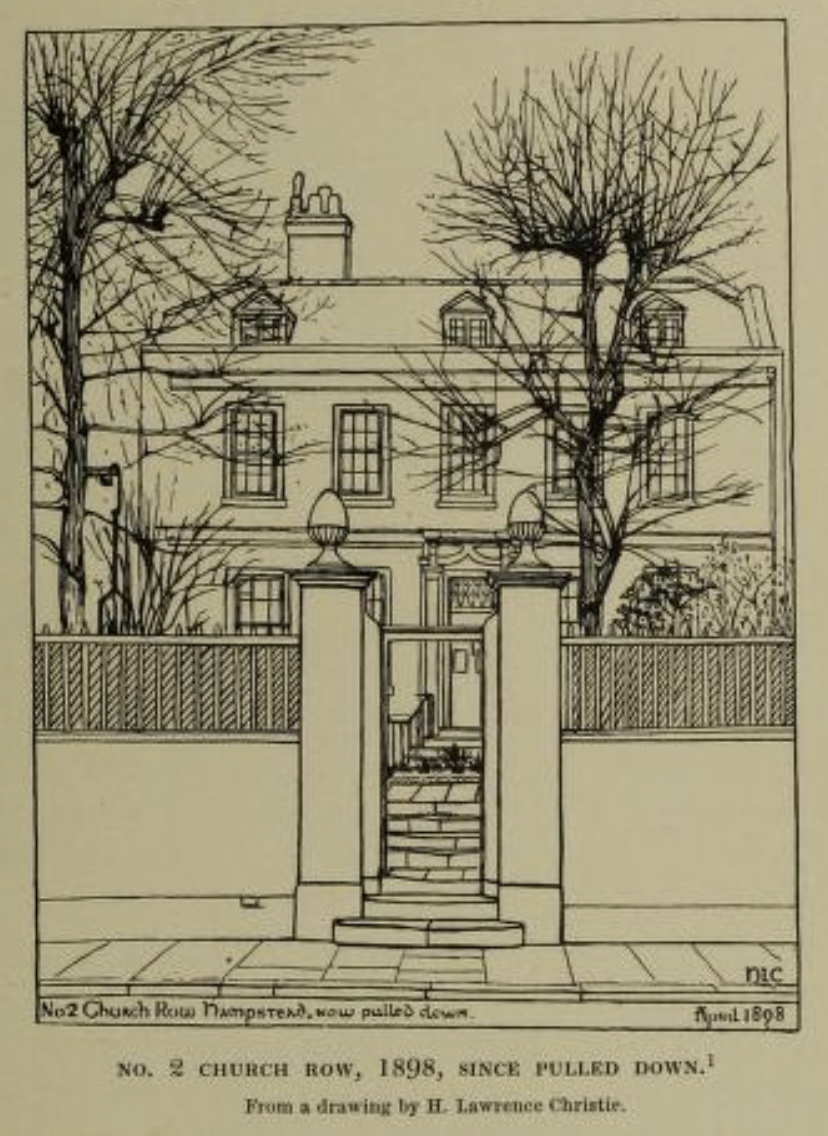

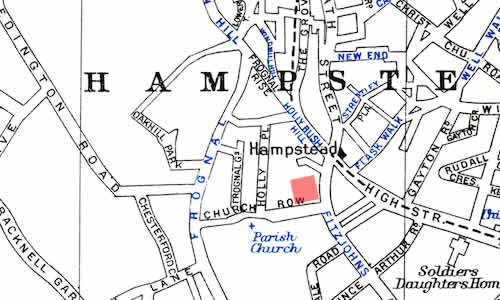

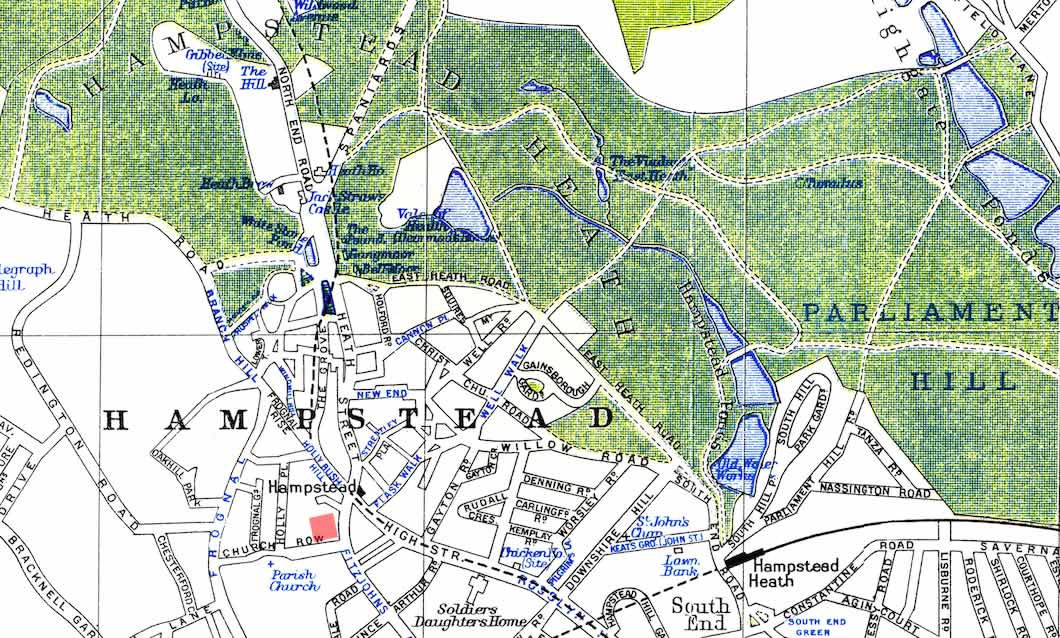

No. 2, Church Row, Hampstead

The residence of the Davenports on Church Row (probably the oldest street in Hampstead),

where, 14 March 1819, Keats dines and then has a nap. I cannot bear a day annihilated in

this way,

Keats writes; and in a letter of 17 March to his brother George and his wife, Georgiana, he goes on to distinguish between a positive and negative form of

indolence—broadly, speculative vs. empty indolence. The subject continues into the

same

journal-letter, but a few days later, on 19 March, Keats attempts to parse indolence

along

with notions of faintness, laziness, languor, carelessness, and effeminacy. He wonders

about

this conflated state and general awareness, and he concludes: This is the only happiness;

and is a rare instance of advantage in the body overpowering the Mind.

What else is Keats up to mid-March? He dines and walks with his publisher and friend (and smokes a cigar), and he manages to get a black-eye playing some cricket.

The dating is unclear, but perhaps after or around 19 March (and definitely before

9 June),

Keats in fact writes a poem called Ode on Indolence (first published 1848;

Keats apparently did not think enough of it to want it in his final 1820 collection).

The

poem, which seems to statically ruminate more than creatively explore, is good but

not great;

we wait for the three figures of Love, Ambition, and Poesy to challenge the speaker,

but they

do not raise him. There is, however, a moment when we perhaps get a sense of Keats’s

great

poetry to come: at the end of the poem, when the speaker bids farewell to the three

uninspiring figures, the speaker tells of visions

to come—genuine visions that might

break the hold that idleness has on him.

And so, in a way, the Ode

on Indolence points to or partly slow-triggers (or is at least an addendum to)

perhaps the most remarkable string of poems in the history of English poetry, all

of which

take up the emotional and philosophical dialectics of joy and sorrow, suffering and

beauty,

pain and bliss, immortality and loss, of time-still and time-moving, and materiality

and

eternity. These poems are often referred to as the great odes

—and they are indeed

great. The order of their composition is not clear. The odes in slightly varying ways

are

applications of Keats’s developed poetics, beginning with his idea of Negative

Capability

(letters, 27 Dec 1817) through to the camelion

poetical

character (letters, 27 Oct 1818) and the creative potential of the disinterested mind

(1letters, 9 March 1819). They also mark ingenious innovations on or adaptations of

the sonnet

form in order to play off a desired voice, preciseness in phrasing, and turns in thoughts

that

are at once subtle and strong.

During March, Keats makes a willed resolution: never to write for the sake of writing, or

making a poem, but from running over with any little knowledge and experience which

many

years of reflection may perhaps give me—otherwise I will be dumb

(letters, 8 March).

This is a significant self-assessment of Keats’s regard for his earlier work, and

it comes at

pivotal moment, given what he is about to accomplish. He clearly implies that he has

previously written merely for the sake of writing (Endymion

comes to mind, as do most of the poems in his first collection), and that he has written

little with mature reflection. If he cannot write with greater and more considered

intention,

he will be silent. At the same time, Keats declares he has some satisfaction of having

great conceptions,

but that he will not spoil my love of gloom by writing an ode to

darkness.

He concludes, I am three and twenty with little knowledge and middling

intellect.

He’s coyly modest and a little playful here, since he knows that Haydon

considers him destined for greatness.

This is all complex and interesting, given that shortly Keats will in fact compose

odes that

move toward darkness, yet turn gloom’s character back upon itself: his Ode to a Nightingale

particularly comes to mind, but instead of a love of gloom

that ends in some final or

wallowing darkness, Keats leaves us with a memorable phrase—tender is the night

—and the

temporal challenge of consciousness and dream.

Keats at this moment also sounds his poetic independence from what he calls that most

vulgar of all crowds the literary.

Despite encouragement from a least a few friends,

Keats remains stuck with his fragment Hyperion, and as he

assesses his options, he entertains the possibility of having to earn a living beyond

poetry

(letters, 15 March). Keats’s state—and finances—are such that the family trustee,

Richard Abbey, suggests Keats enter the hat-making

business, which Keats simply sloughs off. Abbey does get some money to Keats, 60 pounds,

and

he will get another 10 pounds in a few days. His finances are whittling away.

Keats ponders human life as unpredictable: on 19 March, he notes, Neither Poetry, nor

Ambition, nor Love have any alertness of countenance as they pass by me.

And, upon

hearing news from a close friend that his father is dying, he goes on to note that

world has

few moments of pleasure, and that all is mutable: This is the world—thus we cannot expect

to give way many hours to pleasure. Circumstances are like Clouds continually gathering

and

bursting.

His conclusion how the possibilities of response: Very few men have ever

arrived at a complete disinterestedness of Mind.

He wonders what purposes humankind

share, and he wonders if any of his speculations—straining at particles of light in the

midst of a great darkness

—have any bearing on anything. His brewing goal is to make

poetry of controlled intensity out of that straining.

All of this makes clear that, in March, Keats approaches a make-or-break point, with, on one hand, indolence, laziness, listlessness, uncertainties, various serious anxieties, plus a lack of creative buoyancy; and, on the other hand, there is the very real need to forge some kind of stable future. Keats remains afloat, but barely. He has fears he may not have prospects that involve poetry. Paradoxically, this in-between condition may within weeks inspire Keats to begin to compose poetry that reflects his more direct sensibilities and intellect, rather than more unproductive motivations that have to do with pride, fame, judgment, pleasing others, and writing for its own sake. To use his own terms from this month, he will write with the knowledge and experience he has built up and thought deeply upon, and he will do so with profound reflection and tonal composure.

Keats does manage to write a generally underrated sonnet—Why did I laugh tonight?— that captures the depth of his personal uncertainties and the nature of his conflicted, complex temperament. The sonnet, though self-directed, also translates into subjects that outline a more universal human condition: doubt, solitude, mortality, striving, intensity, and frailty. The poem will not be published for more than a quarter of a century after Keats’s death.

As usual, and as mentioned, finances plague Keats into March: not only does he attempt to procure more family money from the balky Abbey, but the same time, his affectionate friend, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, continues to press Keats for a loan. Keats’s own situation makes this almost impossible, and it creates tensions between the two friends, who have been great supporters of each other since October 1816, when they first met via Leigh Hunt, the publisher, poet, and journalist. (Haydon, alas, likes to believe they share the mantle of genius.) Likewise, questions about his own health linger from chronic throat and health issues, which Keats mentions have bothered him for about a year.

In terms of Keats’s poetic progress, then, it is not fully clear that some truly significant poetry will emerge, but some of the mid-March ponderings—about finding something meaningful in passage of predictably unpredictable time, in seeing some splendour within life’s darkness, within the sway of pleasure and troubles—will be fully articulated in the poetry of the emerging 1819 spring.