2-3 January 1819: Moving Forward: What is to be Done & How to Do it

Wentworth Place, Hampstead

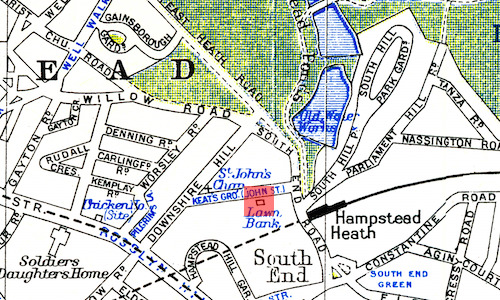

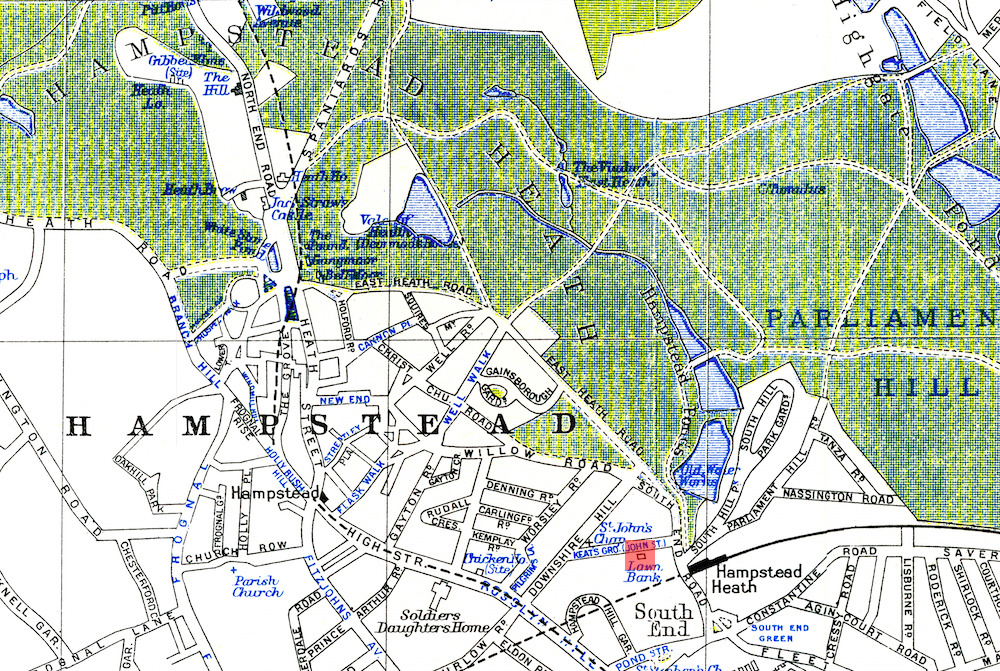

Wentworth Place, called Lawn Cottage

in 1843 and Lawn Bank

in 1868: the

semi-detached double-house where Keats, aged 23, has lived since early December 1818,

at the

invitation of his generous friend Charles Brown

after the death of Keats’s younger brother, Tom (Keats, though, does pay some rent). Wentworth Place, planned and built over

1814-1816, is co-owned by Brown and Charles Wentworth

Dilke, another friend of Keats. Today it is Keats House, a museum dedicated to Keats;

it opened in 1925, and is run by the City of London.

December had been fairly busy. Keats calls and is called upon by his exceedingly kind

friends after Tom’s death (he especially feels

thick

with Brown and Dilke—letters, 16 Dec). No doubt this socializing is both a

diversion and a relief from the three-and-a-half burdensome months he spent nursing

Tom. But

Keats also feels his studies

—his reading and thinking about poetry—are too often

interrupted with his new living arrangement. Keats’s energies are also taken up with

money

issues: one of his close friends asks for a loan; he sees the guardian of the family

trust,

Richard Abbey, to get some cash (credit on

family money managed by Abbey); he goes the bank a number of times; and he also asks

his

publisher, John Taylor, for money the previous

month. His plaguy sore throat

(letters, 10 Jan) continues to trouble him during this

period and into February; it has been a chronic problem for a number of months.

December 1818, too, is the first time we directly hear about a certain eighteen-year-old Fanny Brawne, whom Keats describes in much detail in a long letter to his brother and sister-in-law in America, George and Georgiana (16/18 Dec). Keats is clearly intrigued, and yet a little cagey in what he writes about Fanny. Something seems to be brewing.

The long letter begun 16 December to George and

Georgiana continues on 2-3 January. The letter

opens with a brief account of the distressing last days of poor Tom,

but Keats writes that he does not want to enter

into any parsonic comments on death,

except that he believes in some form of

immortality. As the letter continues toward January (being written over a number of

dates),

Keats gives accounts of his fairly robust activities and friends. He feels he must again

begin with my poetry

—he briefly mentions he is getting on a little with his Hyperion poem (letters, 17-18 Dec), though in a few months he gives

up on it, despite its clear stylistic and tonal advances, particularly in its avoidance

of any

earlier poetic affectation. He also tells George and Georgiana that he’s seen a little

of

their younger sister, Fanny, who at times is

somewhat isolated from Keats by Abbey.

In terms of what Keats thinks about poetry at this time, in his letter he quotes from

his

friend, the prominent literary critic and essayist,

William Hazlitt, who is part of Keats’s intellectual network. Hazlitt is important,

if not crucial, in the formation of Keats’s mature poetics. What is notable is that

Keats

quotes at length from one of Hazlitt’s public lectures, though he didn’t attend any

of the

lectures in this particular series, nor were the lectures published at this point.

In short,

Keats must have seen someone’s copy of the lectures via a mutual friend (likely Reynolds), or perhaps Hazlitt himself gives Keats

manuscripts or proofs of the particular lecture (On the English Novelists,

lecture VI),

maybe when Hazlitt and Keats see each other on 14 December. Hazlitt describes how

the genius

in William Godwin’s* novels resides in their

intense and patient study of the human heart, and an imagination that projects itself

into certain situations.

These appear quite correct

to Keats because they are in

fact tenants that accord with Keats’s own poetics—in particular, in his deep though

ambivalent

admiration for William Wordsworth’s

think[ing] into the human heart

(letters, 3 May 1818), as well as in Keats’s

conception of the camelion poet

(letters, 27 Oct 1818), which derive from Hazlitt’s

earlier thinking about Shakespeare’s genius.

These qualities and characteristics will be embodied in his greatest poetry, still

to come,

but to begin very shortly.

Keats hugely admires (and is heavily influenced by) Hazlitt’s critical tastes, and the two clearly share their views. Keats also enjoys

what he calls Hazlitt’s fiery laconiscism

(letters, 2 Jan). (For more about Hazlitt,

see 22 October 1818.)

Keats does not foresee publishing a volume of poems for a few years (2 Jan), but,

anticipating some progress, he writes to Haydon,

I see by little and little more of what is to be done, and how it is to be done, should

I

ever be able to do it

(14 Jan). This is both modest and uncannily predictive. Again, as

we will shortly see, Keats is indeed able to do it,

and the comment suggests that Keats

has to fully understand and embrace what he thinks about great poetry before he writes

it. The

statement also implies that Keats’s earlier poetry lacks the what

and the

how.

___________________________

*As a footnote: Godwin, philosopher and

novelist, and who for many was a living legend and whom Keats did meet a few times,

had in

fact seen some of Keats’s earlier poetry in manuscript via Leigh Hunt, in February 1817. At least one of Keats’s very good friends, Charles Wentworth Dilke, is (at least according to

Keats) a complete Godwin-methodist

(24 Sept 1819). Godwin is also father-in-law of

Keats’s exact contemporary and fellow aspiring young poet, Percy Bysshe Shelley, whom Keats has met a few times. Keats is in

fact a little wary of Shelley’s goals and enthusiasms; their personalities, background,

and

experiences differ significantly, but both share early promotion and support from

Leigh Hunt.

Shelley and Hunt have a complex and very close relationship—complicated because Shelley

often

has access to money, and Hunt is always wanting; at one point, in January 1822, Hunt

even asks

Shelley to explore the possibilities of a loan with a common friend and fellow poet,

Lord Byron, while Shelley and Bryon are in Italy. For

more about Shelley and Keats, see 18 November 1817.