7-8 August 1818: What Keats takes from the Northern Tour

From Staffa to Cromarty, Scotland

Where, 7-8 August, and at the end of a long northern walking tour, Keats (aged 22)

and his

good friend Charles Brown pause while Keats makes

plans to return to London via a 9-day voyage. Keats cuts the trip short by a month

or two

because of illness—he suffers nastily from chills, fever, and a very bad throat. Brown

stays

behind. In a letter to his grandson, Brown records that, with Keats, he has stumped

642

miles; because of Keats’s condition, Brown writes that it is a matter of prudence

that

Keats return as soon as possible, having taken advice from a physician that he might

not

recover if he continues the walking trip. Brown believes that bad food and fatigue

contribute

to Keats’s condition. Indeed, Brown’s descriptions of the trip towards its end point

to some

very tough and testing terrain and conditions. Brown himself experiences some severe

blistering on his feet.

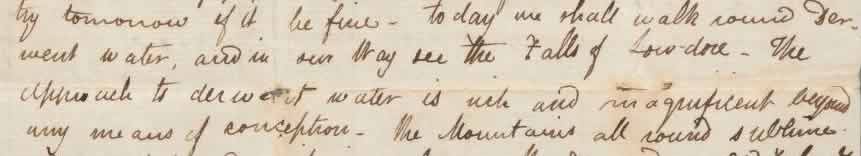

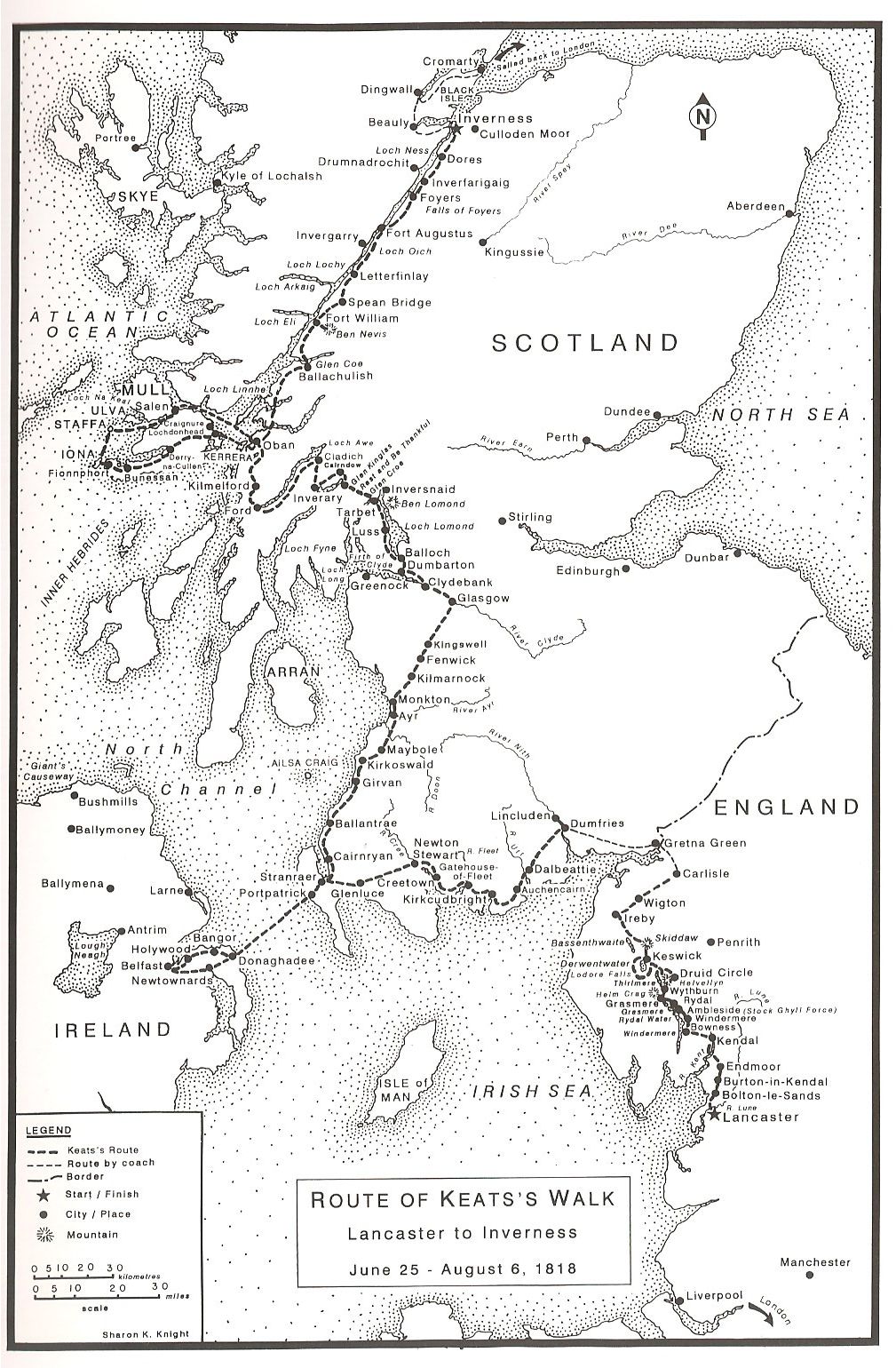

Where did the trip start in earnest? In Lancaster the last week of June, Keats and Brown begin their excursion in the Lake District—in Wordsworth territory, where Keats finds the landscape astonishing and Wordsworth’s canvassing for the Tory party lamentable.

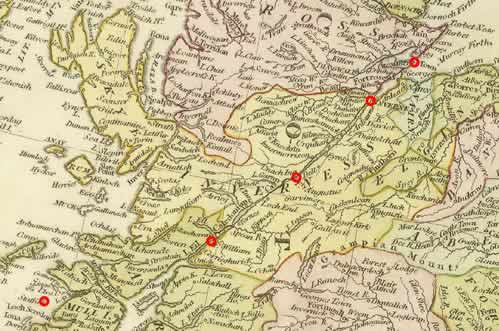

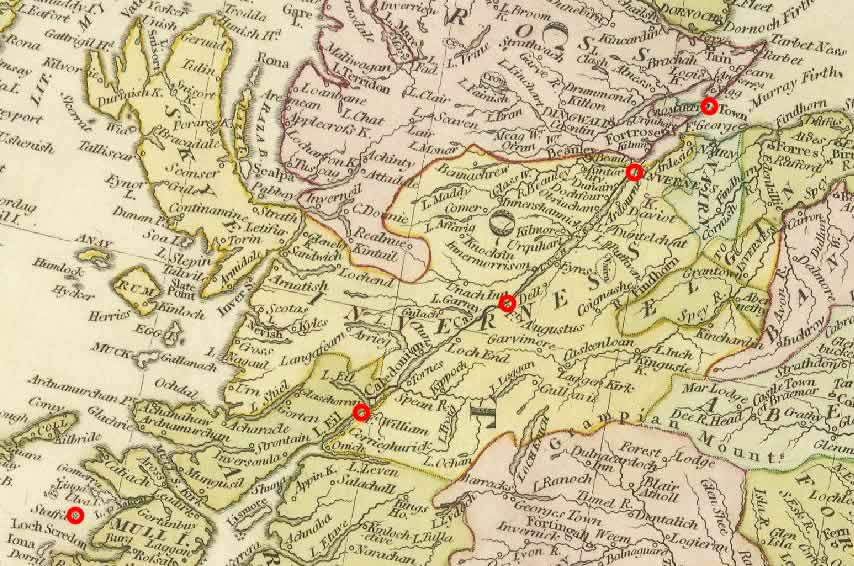

By 1 July, Brown and Keats pass through Carlisle and are in Dumfries, Scotland, to visit the tomb of the poet Robert Burns. Following, they pass through Kirkcudbright, Glenluce, and Portpatrick. A very brief detour to Ireland (via Donaghadee) as far as Belfast reveals poverty more striking than in Scotland. They go through Stranraer, Ballantrae, Girvan, and Kirkoswald. By 11 July, they are in Ayr, Burns’s birthplace, which Keats finds unexpectedly beautiful.

Keats and Brown pass through Glasgow July 13-15, and they arrive at Inveraray by the 17th, where Brown needs some time to rest and heal his sore feet. Within a week, they are in Oban and off to the Island of Mull. On the 24th, they see Fingal’s Cave on Staffa. They head northeast through some wet weather and reach Fort William on 1 August. Beginning very early the next morning they (with a guide) climb nearby Ben Nevis. Keats continues northeast and arrives at Inverness on 6 August; he reports a sore throat.

On 8 August, Keats sails for London from Cromarty, and, with a quick stop at port

of Leith on

the way back, he arrives at London Bridge on the 18th. Shabby and exhausted, by evening

he is

at Wentworth Place in Hampstead. Keats jokes that just to sit on a comfortable chair

is

heaven: punning from a line in Shakespeare’s

A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Keats says, Bless thee, Bottom!

Bless thee! Thou art translated.

Then he goes on to Well Walk to see his younger

brother, Tom, who, to Keats’s great distress, is very ill with consumption—Keats had

left on

his trip thinking that Tom was improving, and now Keats could no doubt see that there

seemed

little hope for Tom, aged 18. That Keats is himself not in very good condition could

not have

made his return anything less than fully disheartening.

The tour is 43 days long; Brown and Keats cover something over 600 miles on foot.

What does Keats take from his trip? And we have to keep in mind that such pedestrian tours of Scotland are part of a growing cultural practice whereby the English traveller believes he or she might gain some cultural cachet. Keats has larger poetic goals, too, but along with Brown he necessarily participates in the ever-increasing practice of tourism.

In a condensed and continuous way, Keats for the first time experiences landscapes

and

natural features that truly impact him, and some of the grander features open up his

perception: lakes, islands, mountains and mountain ranges, seas of mist, waterfalls,

tremendous Glens

(letters, 17 July), caves, crags, and chasms. So too does Keats see

endless varieties of plains, cliffs, meadows, peat-bogs, hills and vales, woods, coastlines

and shores, rivers and streams. Imaginatively, some the features of the landscape—in

their

scale, darkness, and alien nature—will penetrate Keats’s poetic consciousness, and

perhaps

some of this translates in the imagery of his Hyperion projects.

Likewise, in ways relative to the human condition and to his imagination, the meaning

of

nature and natural space challenges Keats via this tour. He also absorbs human history

in new

ways—often in encounters with ancient tombs, ruins, castles, cloisters, nunneries,

monasteries, and graveyards, as well as through old, wretched cottages. He sees towns,

villages, and hamlets—some vibrant, many impoverished, some forgettable. Significantly,

he

experiences the dirt and misery of the human poor

(letters, 9 July) up close, and he

questions if there are solutions to such conditions. In Scotland he feels church oppression.

He encounters everything from rosy-cheeked dancing children to joyless peddlers and

belligerent drunks, from the hardy and stout to the feeble and ailing; and how could

he ever

forget the ape-like, pipe-smoking Duchess of Dunghill in his truncated trip to Ireland?

He is

greeted with kindness, confusion, and mistrust, and he often feels the station of

a true

outsider. That some of those they meet have not even seen spectacles (which Brown wears) reminds him of his specific cultural station; that

Scotland and Ireland are so very different from southern England becomes utterly clear.

Keats

meets many who speak no English, and getting directions from them is frustrating,

humbling,

and comical. Keats and Brown are variously taken as French, as soldiers, Spectacle venders,

Razor sellers, Jewellers, travelling linnen drapers, Spies, Excisemen, & many things

else

(6 August, to Mrs. Wylie).

In William Wordsworth’s Lake District, where

the trip begins, the landscapes take Keats out of himself and to a theme that will

now more

deliberately brace his poetry and poetics: he experiences views that can never fade

away—they make one forget the divisions of life

(26 June). The physical countenance and

power of what he sees surpasses the powers of imagination; such views are, he writes,

beyond any means of conception

(28

June). Here, he declares, he will learn poetry

and write more than ever

in order

to add to that mass of beauty which is harvested from these grand materials

(27 June,

to Tom Keats).

Keats on his tour also confronts what he refers to as Burns’s misery, which in turn makes him confront his own poetic character and aspirations. Burns is a complicated figure for Keats, and though he tries to capture the meaning or significance of the already legendary Burns in a few poems, Keats’s tone toward and understanding of Burns in both his letters and poems remain at the same time inadequate and confused. However, this state does allow Keats to profitably reconsider a topic that teases him out of thought: the relationship of the imagination to actuality—to real, lived life—within the context of human existence; this also includes what for Keats dominates what Burns’s life means and represents: once more, that misery; and Keats is moved to reconcile the relationship between the man and the poet, andd with it, the complexities of what moral obligations should follow a poet. Although Keats identifies with Burns as the independent outsider driven by his own powerful creative goals, Burns, for Keats, is hardly the figure of the ideal poet. Keats cannot also quite figure out why the impressive landscape in Burns territory does not inform—deepen yet expand—Burns’s poetry. (Then again, unlike Keats, Burns, did not have the modelling of poetic presence of William Wordsworth to draw upon.) Burns, for Keats, remains a conflicted figure of poetic fame.

While no doubt all of this strengthens Keats’s experiential reach

in

poetry—especially, perhaps, in terms of understanding the range of human suffering

while

increasing the complexity of his own responses to various sights and conditions—it

also

physically stresses him. Drawing from his own wording, he comes to see that even in

the

most abstracted Pleasure there is no lasting happiness

(7 July), yet, he realizes, it is

all we have and what we must nonetheless pursue.

Keats writes quite a bit of poetry on the trip—quite varied—though most of it occasional, light, or intended to please those to whom he is writing. Some seems to have been written just to pass the time, or just due to the obligation he feels that he should, after all, write something. No doubt being constantly on the road compromises qualitative aspects of the work; that is, compositional circumstances are hardly ideal. Revealingly, none of the fifteen poems he writes during the northern trip are selected for his last volume of poetry, the 1820 collection. When he does attempt serious poetry—as he does, for example, in addressing Burns, being at the summit of Ben Nevis, and seeing Ailsa Rock—the poetry mainly remains oddly stilted; perhaps the compositional circumstances are not conducive to deeper or accomplished verse, or perhaps he is not ready, and has other things on his mind. Perhaps the circumstances push too directly upon him, rather than emerging from within him.

Keats is more changed than directly inspired by the experience of his northern expedition:

there is no way the trip cannot have widened his scope of nature, life, culture, and

history;

and no doubt the trip does, as it were, take him out

of himself before it takes him

back into himself—and when it does, it has to be with deeper senses and a widened

scope,

aspects of which will manifest themselves in his greatest work, the poetry of 1819.

In this

later poetry, in what we could call the third and final phase of poetic development,

the power

and limitations of the imagination will come to be maturely restrained and complicated;

human

mortality in the face of enduring ideas and objects will be explored with controlled

intensity; knowing will be subsumed by beauty; and, perhaps most remarkably, he will

evolve a

voice and poetic forms that reflect and sustain his subjects.

For the sake of drama, this can be put in the form of a question of progress: As Keats literally moved forward on this trip, will what he attempts to gather from the various landscapes profoundly begin to elevate or form his poetic powers; or will the contemplative, complex, and paradoxical turnings of the mind—as it probes problems of consciousness and mortality, as well as the greater meanings of art and the imagination—be the realm wherein Keats’s finds his poetic voice? Or both, profitably yet problematically incorporated? We will have to, as they say, stayed tuned.

Keats began the trip by saying good-bye to one younger brother, George, departing to America from Liverpool—my greatest

friend,

he calls him (6 August to Mrs.

Wylie)—and he ends the trip completely exhausted and with a bad throat, and with the

necessity to care for his other younger brother, Tom, who is sinking fairly quickly

from the

contagious illness of consumption (TB), the wasting

disease. This does not bode well,

especially given Keats’s own lingering physical weakness and what seems to be a family

pre-disposition to the illness. Keats no doubt carried a little guilt in facing Tom, since he left on his walking trip believing

that Tom was improving; it was probably a hope based on fear.

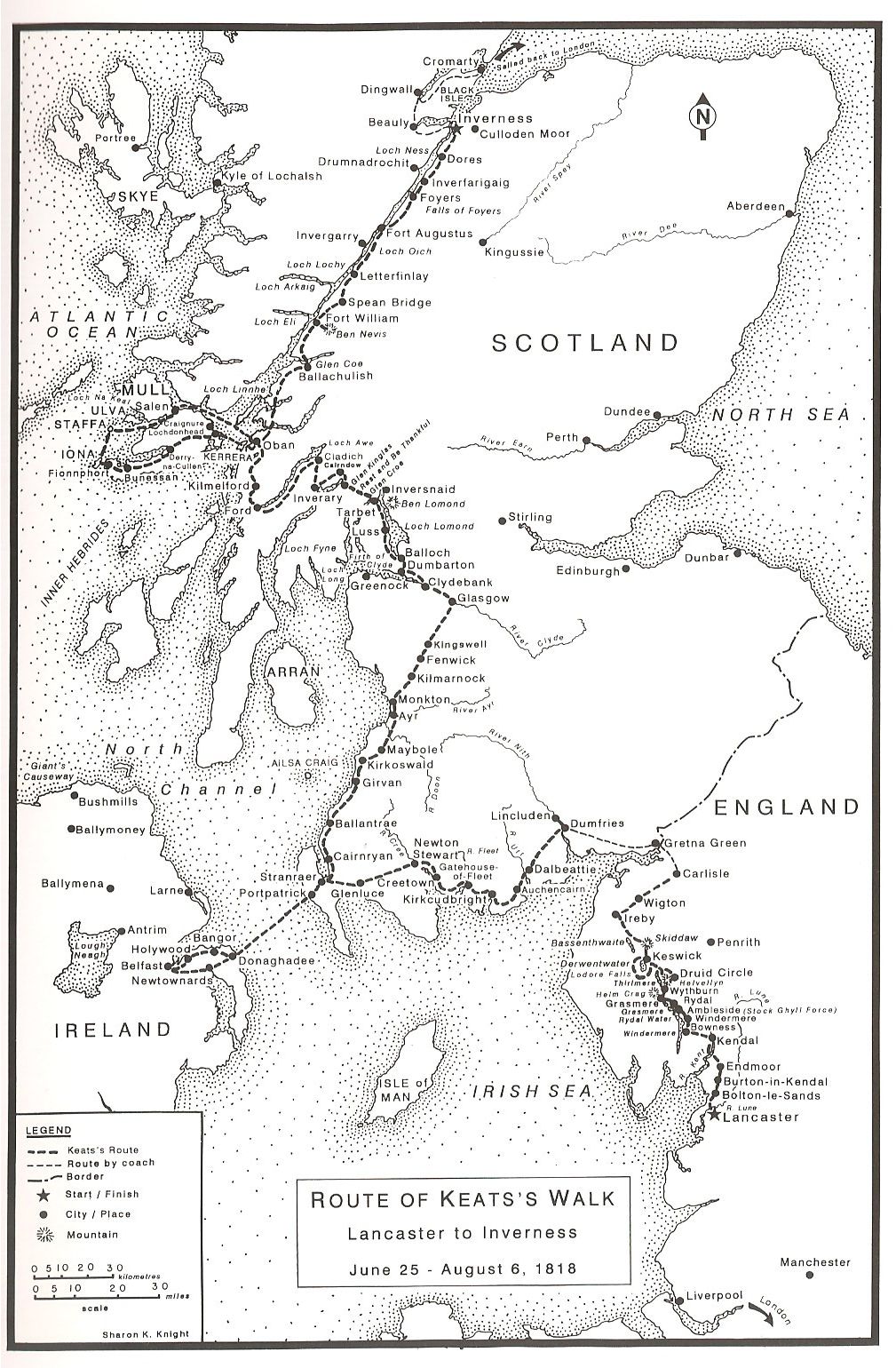

[To view a detailed mapping of Keats’s walking tour, see Keats’s Northern Walking Tour.]