28 May 1818: George Marries, Hunt Attacked, Keats Cringes, Hazlitt Influences

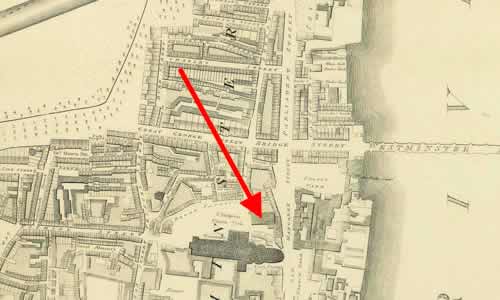

St. Margaret’s Church, Westminster, London

Where Keats’s younger brother, George, marries Georgiana Wylie, 28 May 1818.

Keats, aged 22, signs the marriage register as witness. Keats, however, is not totally

joyful, since the marriage signals the emigration of his brother and sister-in-law

to the

United States. George’s reasons for going are wrapped around opportunities: to make

some kind

of living and to acquire property. In a way, this is a moment of minor reckoning:

as Keats

admits about a year later, My Brother George always stood between me and any dealings with

the world—Now I find I must buffet it

(31 May 1819). The company of his siblings has

always propped him up, which is not surprising given that his father died in 1804,

his mother

in 1810, and his greatly esteemed maternal grandmother in 1814. But now, he’s going

to have

dealings with the world

that may, in a way, force and fashion his responsibilities

and independence.

But, through Georgiana, Keats has at least come to know and greatly respect her family of origin, the Wylies, and he will continue in his friendship with them.

Worth noting: with George about to leave, with his other younger brother (Tom) sick and sliding toward death, and with his younger sister (Fanny) almost sequestered from him by the family trustee, Richard Abbey, Keats must be experiencing feelings of loss—this, despite his supportive friends and often hectic socializing. Keats has no real job, and no exact prospects. Neither does he have a clear idea of what family money he actually has: given Abbey’s obdurate management style, Keats is largely in the dark about his slippery and slipping finances. During May, Keats expresses moments of unease and depression, despite making progress in his thinking about poetry. Facing loss perhaps makes him face other forms—poetic forms—of gain.

By this time, Keats has likely seen the anonymous review of Leigh Hunt’s collection of poetry, Foliage—Letter from Z. To Mr. Leigh Hunt, King of the

Cockneys—in the May edition of Blackwood’s Edinburgh

Magazine, written by Z

—John Gibson

Lockhart. The Letter attacks Hunt’s plebeian

origins and education

as well has is liberal politics, gross vanity, and mainly

ineffectual poetry. There’s no holding back in these Regency culture wars.

Hunt is the target of Z’s Letter, but Keats is

mentioned—first, as the amiable but infatuated bardling, Mister John Keats,

and then as

the person who, with a delicate hand,

crowns Hunt with a laurel. Z has in mind the

sonnet Hunt addresses to Keats in Foliage. Hunt suggests that

Keats, as his protégé, is likewise destined for poetic fame. These sentiments and

barely

closeted egotism are easy marks for ridicule, especially because of the laurel-crowning

poems,

which picture Hunt and Keats placing the wreaths on themselves. (In fact, in another

of Hunt’s

poems in the collection, which is full of poems to and about his circle of friends,

he once

more pictures his wing-sprouting poet-self crowned with a laurel—Fancy’s Party.

) In

referring back to these poems, the October 1819 Blackwood’s

couples Hunt and Keats and nominates them as a pair of blockheads

(p.75). Keats is

aware of how publicly embarrassing the laurel-crowning scene is in Hunt’s poems, and

next

month, 10 June, he writes, a little playfully, I have more than a Laurel from the Quarterly

Reviewers for they have smothered me in Foliage.

In truth, Hunt’s laurel poems are

unblushingly self-centered and propped by indulgent poeticisms. Again, he makes himself

an

easy target, even without any ideological motivations for slamming him.

Keats’s public association with Hunt begins

earlier. In a way, Keats himself signals the connection by dedicating his first volume

of

poems (1817) to Hunt, and by being published in Hunt’s progressive and often controversial

journal, The Examiner. Then, in October 1817, comes the very

first of Blackwood’s attacks on Hunt: On the Cockney

School of Poetry

opens by citing Keats as a son of promise

from a poem by Cornelius Webbe. Keats is sure he is next up for full

ridicule (3 Nov 1817). Even letters to the editor of the relatively obscure newspaper,

the

Anti-Gallican Monitor of 8 June 1817, after suggesting

that Keats be suspended to Bedlam

because of his poetry, ends by saying Keats’s work is

mainly an echo of Mr. Hunt’s; his style in every respect.

And so it does not take Keats

long to both regret and reconsider aspects of his association with Hunt, and not just

because

it makes him easy fodder for the culture wars. But a side of the association with

Hunt

actually aids Keats in his poetic progress: in cringing over his perceived affinity

with

Hunt’s style

of poetry, Keats in 1818 begins to avoid writing poetry that whiffs of

Hunt’s phraseology and comfy suburban posturing, what Z in the October 1819 Blackwood’s calls Hunt’s characteristic Love of sociality

(pp.71-73). Thus poetic independence becomes a stated primary drive for Keats: he

will take

his own direction and not worry about what others say about him. He wants, as it were,

to be

his own master, and not Hunt’s apprentice. He desires deeper prospects rather than

suburban

signature that overwrites much of his early poetry.

And so this month Keats profitably wrestles with ideas about knowledge, imagination,

and

poetic genius that both propel and anticipate his poetic progress. In his 3 May letter

to

John Hamilton Reynolds, Keats theorizes that

both knowledge and poetic strength require a form of speculative knowledge that, fearlessly,

looks beyond and through uncertainty, mystery, and mutability. Keats gets to this

point partly

by gauging the difference between Milton and

Wordsworth. In particular, Keats observes

how Wordsworth explores the burden of the mystery

(so named in Wordsworth’s Tintern Abbey, line 38) and how he thinks

through human

suffering and into the human heart.

This takes us to Keats’s developing ideas—and their

origins—some of which he hints at toward the end of the month.

On 25 May in a letter to his good friend Benjamin

Bailey—in which a noteworthy element is Keats’s description of his depressed,

uninspired, and degenerating state

—Keats mentions William Hazlitt’s recent lectures on the English poets, just put

out by Keats’s own publishers, Taylor & Hessey. Keats in fact has just dined with Hazlitt,

and he attends some of Hazlitt’s popular Surrey Institution lectures earlier in the

year. In

hindsight, what is particularly striking but often ignored is that core features of

Keats’s

remarkable poetics derive directly from Hazlitt’s ideas about the nature of Shakespeare’s genius as described in his third lecture, On Shakespeare and Milton. Shakespeare’s mind, Hazlitt observes,

has no peculiar bias

—He was least of an egotist that it was possible to be. He was

nothing in himself; but he was all that others were, or that they could become. [.

. .] His

genius shone equally on the evil and on the good, on the wise and the foolish, the

monarch

and the beggar.

Shakespeare had only to think of anything to become that thing

;

he could instantly enter and become whatever subject or character he conceived, being

able to

pass from one to another.

Like a ventriloquist, he throws his imagination out of

himself.

Keats obviously echoes and channels these ideas (and the critical lexicon) later in

the year

when he is on the verge of producing his own great poetry. He does so to Richard Woodhouse on 27 October in what amounts to his

principle statement about the poetical Character.

Keats writes that the poetic type he

aspires to in fact has no character—it enjoys light and shade; it lives in gusto, be it

foul or fair, high or low, rich or poor, mean or elevated—It has as much delight in

conceiving an Iago as an Imogen. [. . .] he has no identity—he is continually in for—and

filling some other Body— [. . .] he has no self.

Keats here famously calls this the

camelion Poet,

as distinguished from the wordsworthian or egotistical sublime,

but no doubt it is inspired by Hazlitt’s thoughts on Shakespeare’s plastic

imaginative powers. Using

Hazlitt’s terms, Keats aims to write poetry without bias

and egotism. It turns out he

aims well.