April 1818: Endymion Published & Post-Endymion Keats; Pursuit of Beauty & Knowledge—and a Walking Tour

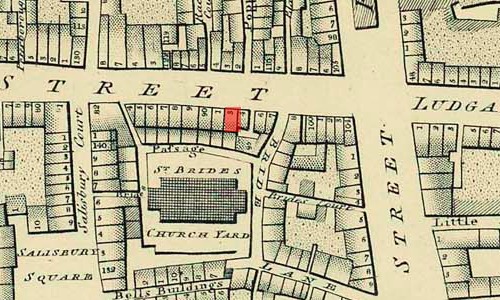

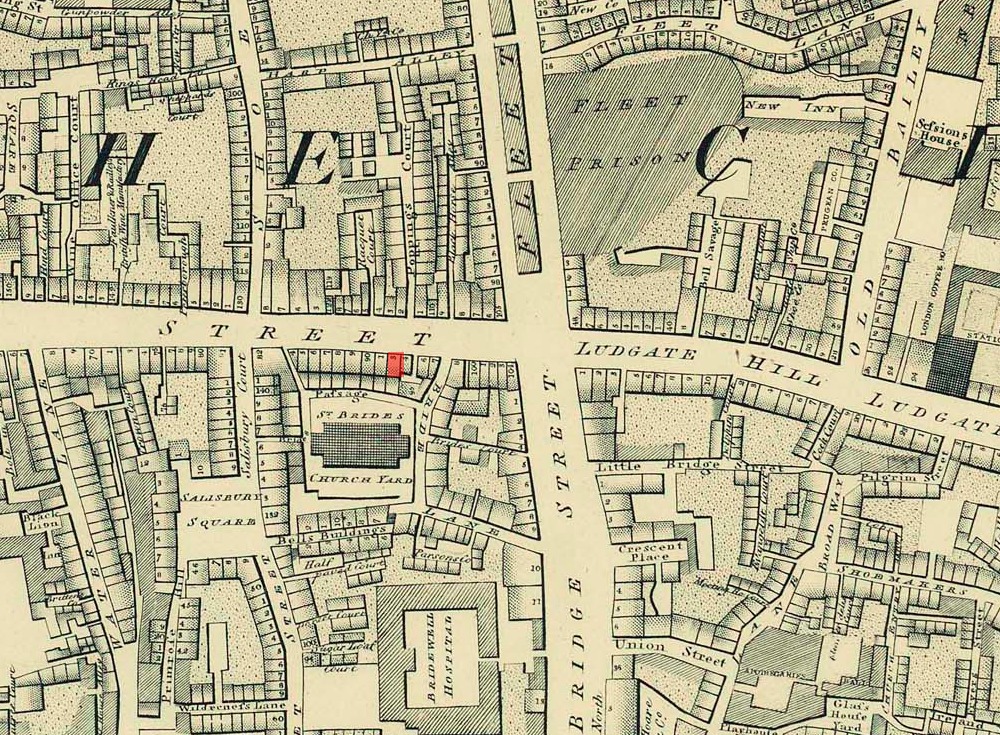

93 Fleet Street, London

The offices of [John] Taylor & [James] Hessey, Publishers/Booksellers, launched 1806.

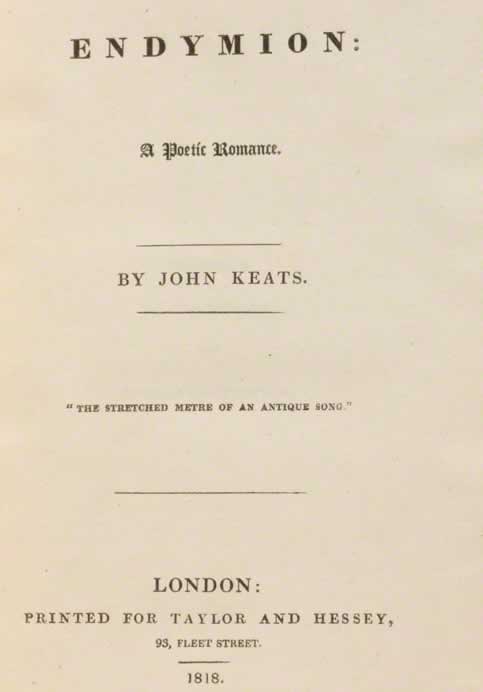

In the last week of April 1818, Keats, aged 22, publishes his Endymion with Taylor & Hessey, with whom he will also publish his next (and final) 1820 collection. Among others, Taylor & Hessey publish work by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Hazlitt, Leigh Hunt, Thomas De Quincey, and Charles Lamb. About two-and-a-half years later, Taylor & Hessey will report a loss on Endymion of over 100 pounds, yet, from the beginning of their relationship with Keats, they fully believe in him and his eventual success as a poet.

Keats calls the 4,050-line Endymion

a test, a trial of my Powers of Imagination

(letters, 8 Oct 1817), but in the poem’s

preface, he awkwardly apologizes for its (and his own) immaturity; thus, from some

quarters,

Keats opens himself up to public belittling and criticism: a glib paraphrase of the

preface

might be, Yes, I know the poem is pretty bad, but take it easy on me. I hope at some point

to do better than this.. So Keats is right: the poem’s overall qualities are

indifferent and uneven. There is also some struggle over the preface to the poem with

his

friend John Hamilton Reynolds, who is working

with the publisher, but Keats expresses that he cares absolutely nothing about the

public,

which he sees as an Enemy

—and he hates Mawkish popularity.

The only humility he

feels is toward the eternal Being, the Principle of Beauty,—and the Memory of great

Men.

He feels it is time to enlarge my vision

(9 April).

Keats has many up-and-down moments in the year-long compositional history of Endymion. The poem has just a few strong passages, and Keats is

perceptive enough to see that, even with its weak foundations, it serves as a necessary

failure in his poetic development; in terms of the poetry, there are passages of both

strain

and carelessness. Even before completion he admits to having a low

opinion of the poem

(28 Sept 1817), and after completing it he points to its slip-shod

nature; with Endymion in mind, he writes, I was never afraid of failure

(8 Oct 1818).

The most famous review of Endymion is by Z

—John Gibson Lockhart—in the August 1818 Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine: to a significant degree Z

ridicules the poem for being under the toxic sway of Leigh

Hunt’s Cockney School of poetry

—a slight that neatly, and purposefully, fuses

politics and poetics.

Though the review is also openly coloured by partisanship and class, Z without the ideologically-inspired invective is generally

correct: the poem tackles no sustained problem; it possesses only a few moments of

deep or

complex sense; and it barely has anything original to contribute to the story of (to

paraphrase Keats’s own potted plot, letters 10 September 1817) the Moon’s excessive

love for a

young, solitary, handsome Shepherd. Moreover, that Huntian style is something Keats

needs to

move away from in order to progress: as Lockhart puts it, Keats has adopted Hunt’s

loose,

nerveless versification, and Cockney rhymes.

This, again, is generally correct, and not

unnoticed by Keats, with or without Z’s critical panning. Other, even favorable views

of the

poem, unfavorably note the same Huntian strains. The point was certainly not lost

on Keats.

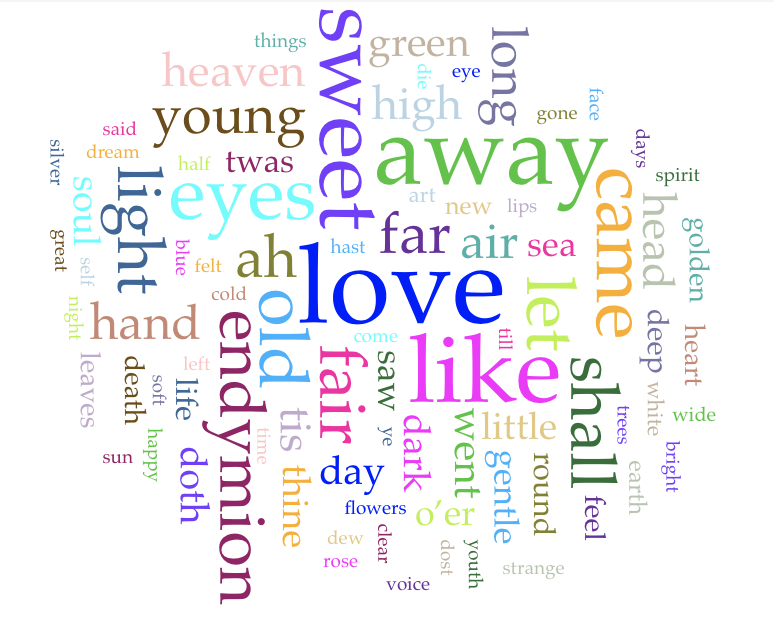

In sum, the completion of Endymion does not show that Keats is a great poet; it does, however, show that

he is a dedicated poet, one determined to profit from missteps and grow out of his

poetic

immaturity. The poem’s only saving points are those when it brushes up against issues

and

topics like dream/reality, mortality/immortality, and empathetic fellowship; but,

at best,

these passages take up not much more than about 15% of the poem’s total content. A

tough

editor in the mood for cutting that the poem and end up with a decent 500-line lyric

poem, one

mainly void of bowers, flowers, leaves, trees, mists, shades, mosses, drooping things,

green

things, bright things, airy things, fair things, sweetness, and embroidered, embowered

scenes;

you might imagine this editor writing, And please, no more sighs in the poem! And as for

things gold and silver—what? Hair, rocks, sand, buds, palaces, bugles, lakes, rivers,

brooks, clouds . . . cut, cut, cut . . .

. This might sound a little tough and glib at

the same time, but Keats’s own friend—and exacting defender of his poetry—the critic

William Hazlitt, says as much; in his 1822 essay

On Effeminacy of Character,

he notes that while Endymion is delightful and full of fancy

and sweetness, it is deficient in style and substance, with nothing tangible or palpable,

with

no real action or character. Hazlitt’s conclusion: All is soft and fleshy without bone or

muscle.

Hazlitt is right; to follow the metaphor, after Endymion, Keats will have to work out—and

Keats knows as much, and does.

April reveals Keats hatching plans for a walking-tour of Scotland and northern England

with

his close friend, Charles Brown. With some

unbridled enthusiasm, to Benjamin Robert Haydon

he writes that this expedition will necessarily establish his life’s aspirations:

the trip

will make a sort of Prologue to the Life I intend to pursue—that is to write, to study

and

to see all Europe at the lowest expense. I will clamber through the Clouds and exist.

I will

get such an accumulation of stupendous recollections that as I walk through the suburbs

of

London I may not see them

(8 April). And toward the end of the month, with Endymion just about

completely behind him, he firmly tells Taylor

that his cavalier days are gone by,

and that there is but one way for me. The road

lies though application, study, and thought

: I find I can have no enjoyment in the

world but continual drinking of knowledge

—quoting Solomon, get wisdom - get

understanding

(letters, 24 April). Keats ends the letter by hoping to talk with Taylor

about what books he might take with him on his quest for knowledge-seeking.

A few days later, to his friend Reynolds,

Keats’s enthusiasm for future directions continues: he has plans to master Italian

and Greek,

and, as in his letter to Taylor, he expresses that his interests in philosophy and

metaphysics

are growing, and he longs to feast on old Homer, as we have upon Shakespeare

and Milton (letters, 27 April). Keats, then, continues to map out the course of his

poetic progress. He has clear plans and high hopes.

With these kinds of forward-looking and determined comments, Keats clearly signals

a new

phase in his development as a poet, a phase we might call post-Endymion. With the Principle of Beauty

as his premier maxim, and with an

expressed desire to pursue knowledge with deliberate study as another maxim (to get wisdom

- get understanding

), we hear a purposeful poet in April 1818. By the end of the year

and into 1819, such determination takes him to his greatest poetry. The road ahead,

though, is

not clear, and he will have to see his way past the death of his younger brother,

Tom, at the end of 1818, and he will also have

moments of uncertainty, anxiety, depression, fatigue, and indolence—not to mention

acute

financial uncertainty, lingering throat problems, and complex love for a certain Fanny Brawne. Great things are never simple; life is

not a map.