28 December 1817: Haydon & the Immortal Dinner

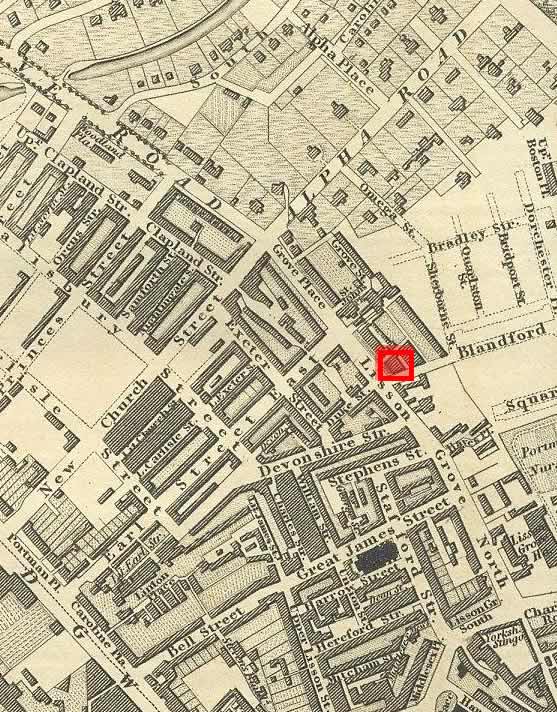

22 Lisson Grove North, London

22 Lisson Grove North is now No. 1, Rossmore Road.

Keats dines at Benjamin Robert Haydon’s residence at 22 Lisson Grove North. Haydon is a fairly well-known painter of mainly historical subjects, and acquainted with a number notable figures of the era. Charles Lamb (poet and essayist) and William Wordsworth (arguably the greatest poet of the age) are present at the dinner party. Later in the evening, John Kingston, a rising civil servant, arrives, after getting himself invited; he is Wordsworth’s superior, in effect, though at first, and apparently somewhat awkwardly, Wordsworth is not aware of Kingston’s status—he had never met Kingston but they had some correspondence. At this point, then, Kingston’s presence may have made Wordsworth act with some restraints or pretensions. Two others also show up late—the father of a couple of Haydon’s students and a young surgeon (Joseph Ritchie) on his way to explore the River Niger. Perhaps conspicuously absent are Leigh Hunt (Haydon is miffed that Mrs. Hunt has not returned some recently borrowed silverware) and William Hazlitt (he has published some negative comments about Wordsworth).

In truth, the evening becomes an odd mix of actions and reactions. Lamb eventually gets drunk and giddy enough to mock Kingston’s apparently vacuous comments, including a naive question about Milton’s genius that got some of the party laughing quite uncontrollably. But probably not Wordsworth.

Haydon organizes the evening since he is keen to

show (or rather, show off) his progress on a massive, ambitious painting that, within

the

large crowd pictured on the painting, includes Keats, Lamb, and Wordsworth, as well as figures like Newton and Voltaire:

Christ’s [Triumphant] Entry into Jerusalem. Haydon invests

much time and emotion in the painting—too much, in fact. (Haydon is very slow as a

painter

because of extremely poor eyes—the painting took over five years to complete.) The

painting is

impressive in its scale, fairly skilled in its representations, but it lacks anything

truly

arresting or innovative, and its general sense is postured and static. We could borrow

from

what Keats observes is lacking in another large canvas he views this month, Benjamin West’s Death on the Pale

Horse. Keats notes what West’s painting lacks: there is nothing to be intense

upon

(21/27 Dec). The same, in fact, could be said for Hazlitt’s painting, though Keats at this point is still quite

taken with Haydon’s reputation and connections—not to mention his unfailing energies

and

belief in himself—to doubt his friend’s artistic prowess.

With its great conversations, recitations, arguments, wit, and a little mischief,

Haydon privately christens the event the immortal

dinner,

and history has stuck with the name. The evening is intriguing enough that two

books have been written about it.

Keats, very social during this period, sees Wordsworth a few times around the end of 1817 into early 1818, though Keats becomes disappointed that Wordsworth has (contrary to his earlier values and beliefs) become a staunch Tory supporter. Keats will observe that Wordsworth is reverentially protected by his inner circle of mainly his sister and wife. When Wordsworth leaves London and returns home to the Lake District, more than a few people are glad to see the back of him and his perceived pomposity.

Keats also during this period begins to develop a poetics that will, in about a year,

result in poetry remarkably superior to his earlier work and to Endymion, which he revises and corrects at this time.

Art, Keats writes, must be strong enough to make all disagreeables evaporate, from

their being in close proximity with Truth & Beauty

(21/27 December). This

can be read as a statement of purpose; his poems of 1819 are proof of concept.

After sharing initial gushing mutual admiration with Haydon, and after Haydon influences Keats’s developing ideas about art (as well weaning Keats from Leigh Hunt’s influence), Keats’s regard for Haydon fades, mainly over the painter’s negative estimate of some of Keats’s friends, a loan made by Keats to Haydon that was not paid back, and a book of Haydon’s that Keats did not return (he actually lost it). Haydon was well into developing a track record of acting quite unevenly, very high-handedly, and both aggressively and defensively with those he comes to know and who otherwise might be staunch supporters. Although often jovial, Haydon increasingly became an uneasy mix of vanity and sensitivity, often making him at once both victim and champion. Temperamental is a kind term to describe him.

Over time, Haydon’s fortunes falls, and in 1846, aged 61, with chronic financial and personal problems, he commits suicide by shooting himself once and cutting his own throat twice. He is probably best remembered in the context of his friendship with Keats and in his support of the Elgin Marbles. In truth, Haydon’s greatest artistic gifts are defined (and remembered) in a few portraits, rather than his large (often too large, and too uneven) canvasses. The best and most interesting work by Haydon perhaps appears in his autobiographical writing and in his extensive diaries, where the one consistency is Haydon’s belief in his own genius and his destined place in restoring High Art to the British public. But he failed. Poor Haydon. [For more about Haydon’s character and suicide, see 3 November 1816.]

We cannot say that anything at this dinner gathering directly influences Keats’s poetry or poetic progress. But what we can say is that Keats, in finding himself at such events and with such company—with older and well established figures like Lamb, Wordsworth, and Haydon, who already carry a strong intellectual track record and possess significant cultural cachet—realizes he does belong there at that table and on that canvas.* He can, as it were, hold his own. And this, at least, must fortify his ambitions as he moves closer to achieving his own independent poetic goals.

*See here for a graphing of Keats’s social and intellectual network; this also shows the role Haydon plays in connecting Keats to others.