May 1817: Bo-Peep, Isabella Jones, & Endymion as a Coming-of-Age Poem

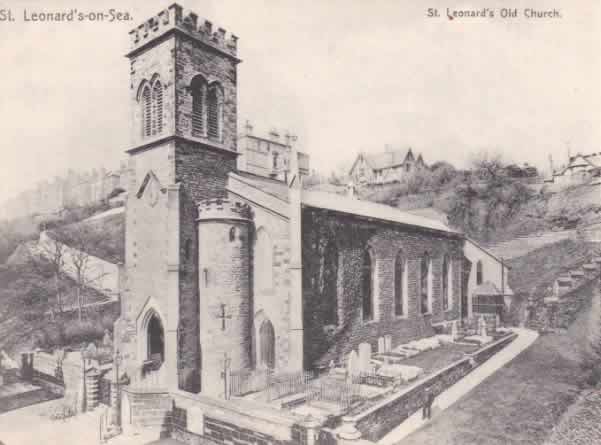

Bo-Peep (now St. Leonards-on-Sea)

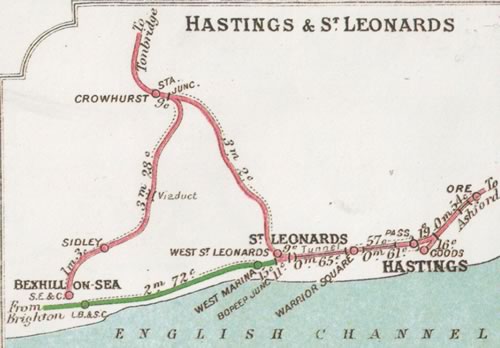

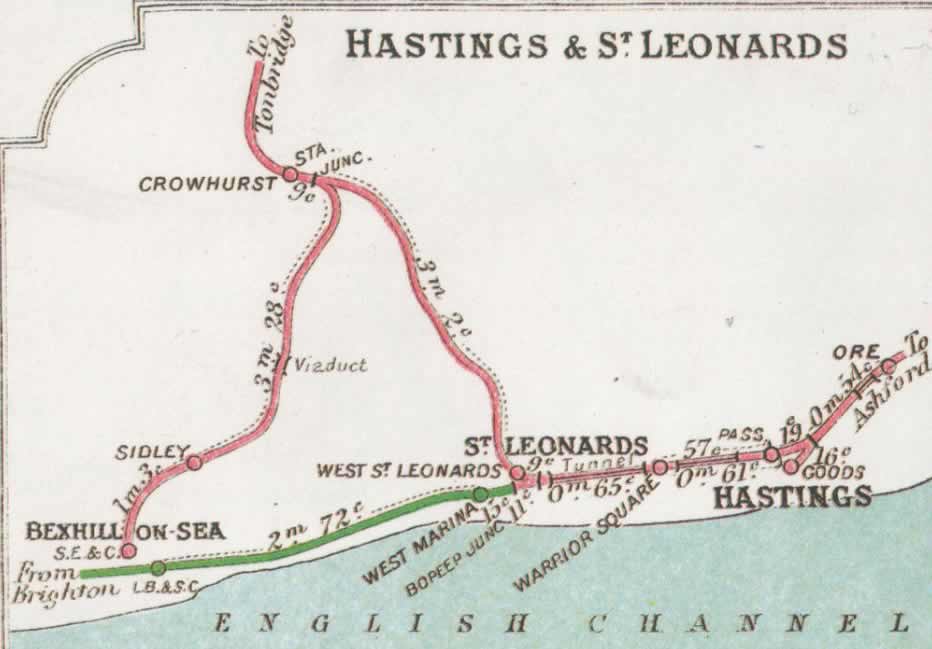

Keats’s writing trip to begin work on his long poem Endymion begins on the Isle of Wight mid-April, continues to Margate and then to Canterbury in May, and finally to the village of Bo-Peep (now St. Leonards-on-Sea), close to Hastings,* by the end of May. With the suggestion of his very close friend at this point, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, Keats (aged 21) stays at a small inn called The New England Bank.

While in the area of Bo-Peep toward the end of May, Keats meets an alluring, smart,

stylish,

and, it seems, experienced woman of independent means, with whom he has some kind

of romantic

encounter. Her name is Isabella Jones—Mrs.

Jones,

though there is no evidence if she is a widow or just a woman of particular

elevated means (that is, Mrs.

was sometimes used as an honorific term, and not a term

to suggest being married); we aren’t even fully certain of her age. But whatever,

Keats never

quite forgets about her. He has later meetings with her, including, in October 1818,

a chance

visit to her very cultured (or at least artsy) residence in the central London district

of

Fitzrovia, which impresses and perhaps tantalizes Keats with its music, aeolian harp,

art,

booze, busts, books, and birds—as well as bronze statue of Napoleon, which suggests

something

of her free-thinking sympathies; and though Keats (in his own words) had warmed with her

before and kissed her,

at this later point she tastefully turns down his apparent

advances in favour of pressing him pressing her hand upon departure, which seems not

to have

bothered Keats too much. Nevertheless, Keats no doubt hoped for at least a bit of

cuddling and

smooching (and warming), something like he experiences here, in Bo-Peep. [For more

about this

subsequent meeting with Mrs. Jones, see 24 October 1818.]

Keats will later write to his brother, George,

I have no libidinous thought about her

(22 Oct 1818), though, again, it is hard to

determine Keats’s feelings or intentions, since there seems to have been an agreement

between

Keats and Isabella to keep their connection quiet between given some mutual acquaintances.

We

find, too, that the Lady

gives Keats many presents of game

that Keats re-gifts

(19 Feb 1819).

Isabella Jones is perhaps the inspiration for a couple of indifferent poems of longing written in 1817: Unheard, unfelt, unseen and Hither, hither, love. She also later seems to have suggested to Keats that he write a poem about the one evening a year when young virgins dream about their future husbands; the resulting poem is one of Keats’s first sustained masterpieces, The Eve of St. Agnes, composed early 1819. Finally, what we also know is that Mrs. Jones is or becomes part of a social circle that fully intersects with Keats, and in particular Keats’s publisher, John Taylor, and includes other writers revolving around John Scott’s The London Magazine.

At his point, with much encouragement from Haydon, Keats works hard on long, classical romance, Endymion. However, he begins to feel a little overwhelmed by the task ahead. Keats’s

idea is simple enough: a substantial poem will be his self-testing trial of invention

and

imagination. And given that he will (unfortunately) declare in the poem’s eventual

preface

that Endymion exhibits adolescent sentiments and great

inexperience, and is hardly worthy of publication, the poem represents, in effect,

a fairly

deliberate coming-of-age project. In a way, and at best, the poem’s plot of a young

poet-like

shepherd in search of the ideal of his imagination is allegorical of Keats’s own desire

to

become a poet: a mortal poet in search of his own ideals of immortal truth and beauty.

Keats

will later say that good poetry should feel natural and surprise by fine excess

(letters, 27 Feb 1818). But the trouble with Endymion, a poem

that too often luxuriates in random description, sensation, and vision, is that there

is

excess

without it necessarily being fine

—there is, in its wandering manner,

and in spilling rhymes that over-determine sense, much obvious artifice and not that

much that

feels natural. Despite a few passages that look forward to better poetry, the poem

is much

more an act of perseverance than of achievement.

Haydon encourages Keats, in isolation, to

devote himself to reading and studying. (Shakespeare is the presiding literary presence on the trip, though this is not

overly reflected in Endymion; there are some dashes of A Midsummers Night Dream, and, like Shakespeare at moments, Keats

attempts to conjure a little medieval romance.) Haydon also urges Keats not to despair

or be

tormented by anxieties, but instead move forward without hesitation or fear

: your

energy will give you strength, & hope & comfort

(Haydon to Keats, 8 May 1817).

Keats responds by declaring that he is reading and writing about eight hours a day

(letters, 10 May). Despite this, Keats’s mood is uneven, and for moments on the dark

side: he

writes of a Morbidity of Temperament

that, as his Enemy,

strikes him at

intervals and sometimes leaves him inspirationally hampered (letters, 11 May). A few

days

later, he writes of a Brain so overwrought

and the effects of a Mental Debauch

(letters, 16 May). So what is going on with Keats? Chronic depression? Some kind of

anxiety

disorder? It might be attractive to toss some of these modern labels Keats’s way,

but given

Keats’s sensitive and hyper-articulate nature, what we have is a young man in search

of

direction but simply caught between hope and uncertainty.

At this very early stage in his poetic progress, Keats, venting to Haydon, begins to condemn Leigh Hunt’s self-declarations (delusions,

Keats calls them) of poetic

greatness (letters, 11 May). This is somewhat surprising, since Hunt, as perhaps one

center of

London’s liberal-progressive artistic and political intelligentsia, is really the

first to

discover and promote Keats, beginning in the second half of 1816. Keats begins to

think that

Hunt’s style of poetry and Hunt’s notions of his own poetic worth do not suit his

own tastes

and developing program to write enduring poetry. Yet despite Keats strongly lamenting

Hunt’s

claims to being a great poet to Haydon, Keats has just written to Hunt, praising his

journalist prowess, quoting some Shakespeare, and confessing his own anxieties and insecurities about poetry and fame,

even if for the last few days he has felt more confident.

Keats also gives Hunt a kind

of progress report on Endymion, that he is working on it every day, and that he hopes he doesn’t

miss the Goal

with his poem (10 May). Hunt will later off-handedly slight Keats’s

poem, which Keats hears about. Keats thought that perhaps Hunt was miffed that he

had not been

consulted enough in the writing of the poem.

But back to Hunt for a moment: As a writer, he was, in effect, a jack of all genres. He wrote poetry and prose in all kinds of styles and for all kinds of purposes; he is nothing short of prolific. But if we were to point to his greatest contribution (besides being an important publisher and editor), it was in the realm of the essay, within which he fairly innovatively ranges from high politics to the lower familial. The one joining factor in his writing: his voice and opinions are generally independent, and his tone is very much his own. Hunt also had a pretty good nose for literary and artistic talent, and was often a supporter of such talent ahead of contemporary critical tastes.

Keats, as a young poet, does the right thing by tackling the Endymion project, especially if viewed as an experiment or exercise in testing limits, voice, and form. We can thus expect and see that, at this point, his poetic aspirations are compromised by dashes of minor recklessness and by developing, uneven skills. Keats is, after all, a poet of unmeasured accomplishment and measureless potential—so his closest friends believe. We will also find that, for Keats, copying out the poem in early 1818 for publication (in late April 1818) is an important moment: he sees even more clearly the poem’s limitations and patchy qualities. He vows not to write in this mode again. Keats does, however, hope to call upon the Greek tradition in future writing after he accumulates some experience (so he writes in the eventual preface to Endymion); and, by the end of 1818 and in July 1819 he actually does make a return with a couple of attempts to build upon the titanic Hyperion story; and though the poetry he resultantly writes is, qualitatively, far beyond what Endymion achieves (in two poems we know as Hyperion and The Fall of Hyperion), the Hyperion project remains as two impressive fragments.