9 October 1816: An Era in My Existence

: Leigh Hunt, a Crash Course, & taking

possession with Chapman’s Homer

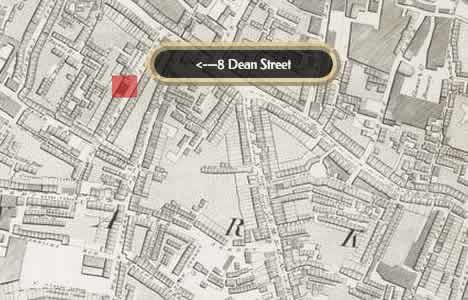

No. 8, Dean Street, Southwark, London

Where, in October 1816, Keats lodges with his younger brothers, George and Tom. Keats describes the general area as a bit of a

beastly place in dirt, turnings and windings

(letter, 9 Oct 1816). Indeed, the

location was completely unfashionable, though for Keats it places him fairly close

to Guy’s

Hospital, where he is training. The brothers take the second floor of the address,

which may

have been over a candy shop. Today, Dean Street (also once referred to as Weston Street)

is

called Stainer Street, off Tooley Street, though the area is developed for the London

Bridge

station.

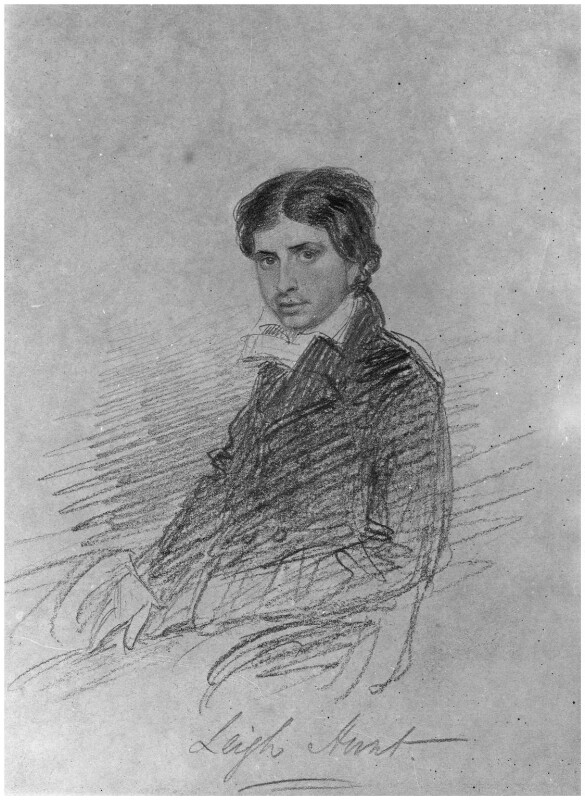

Through Charles Cowden Clarke (the son of

Keats’s former headmaster), Keats this month meets the famous Leigh Hunt—publisher, journalist, poet, critic. This immediately and

crucially expands Keats’s social and cultural circle, which now suddenly includes

established

poets, writers, publishers, critics, and artists. Clarke (who tutors some of Keats’s

earlier

literary tastes) has shown a little of Keats’s poetry to Hunt. On 9 October, the prospect

of

meeting Hunt causes Keats to write to Clarke that it will be an Era in my existence

to

be acquainted with those who genuinely admire great poetry.

Through Hunt, Keats almost immediately meets Benjamin Robert Haydon (the artist and vocal champion of art) and John Hamilton Reynolds (poet and reviewer). Both begin to have some influence Keats’s tastes and ideas; they also further widen Keats’s circle of acquaintances particularly in the publishing and art world, of which Keats would have known very little; and both (but particularly Haydon) see that in order to poetically progress, Keats should move from Hunt’s influence. In short, the last few months of 1816 and into early 1817 mark, for Keats, a kind of crash course on the Regency London literary and artist culture. In particular, Keats will be thrown face-first in the culture wars of the time, with Hunt’s circle generally falling into he progressive, liberal camp.

[For more on the history of Keats’s evolving relationship with Hunt, see the end of 6 March 1818; and see here for a flowchart showing Hunt, Haydon, and Reynolds as key nodes in Keats’s social and literary network.]

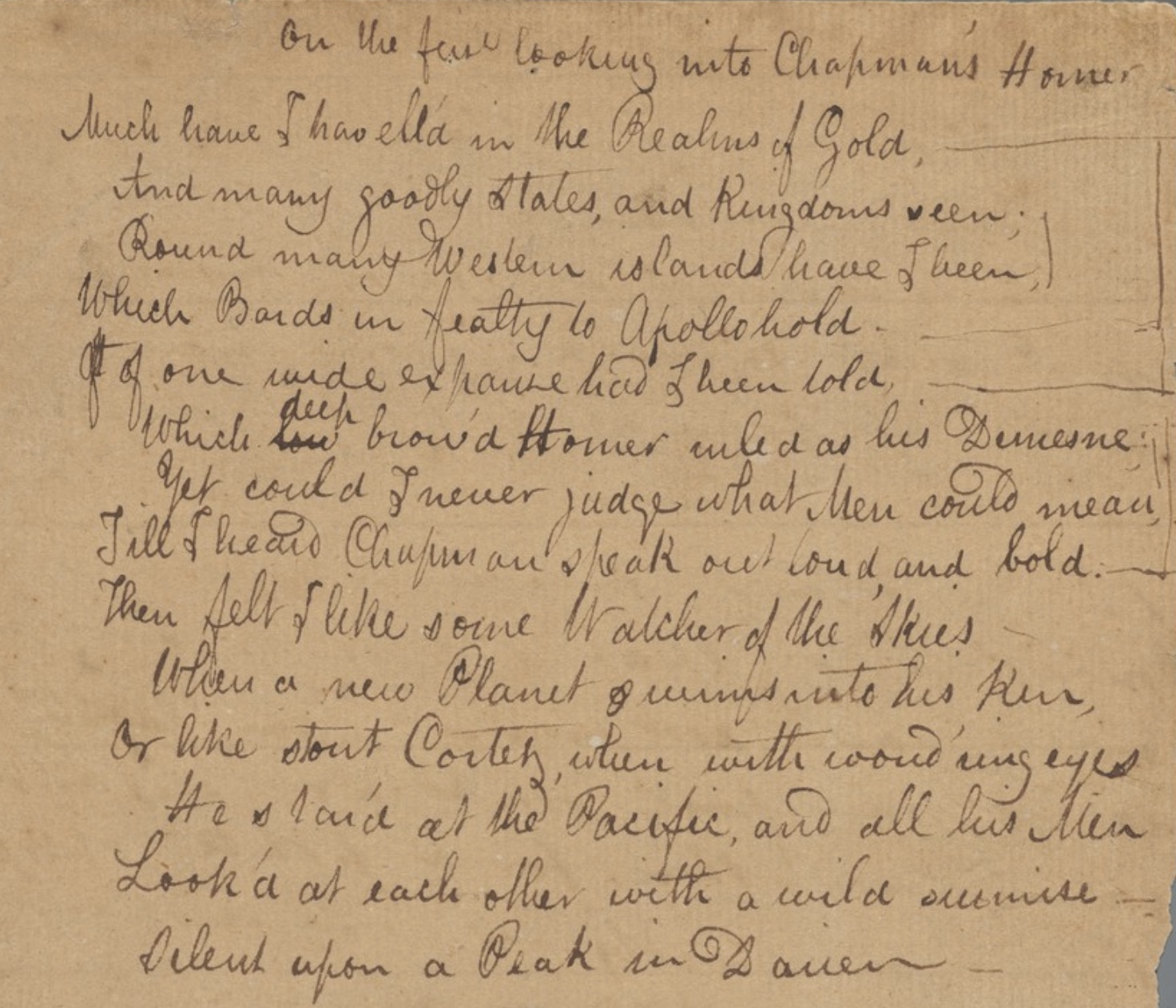

This month Keats writes what is generally considered his best early poem, the

ever-anthologized On First Looking into Chapman’s

Homer. Hunt’s words about the poem, which he writes about ten years later (and

with some clarity of hindsight), describe it in terms of Keats’s progress, that with

the

sonnet we see the new poet [Keats] taking possession

—that is, the poem is a marker of

Keats’s growing poetic maturity. Keats writes the poem after pouring through a copy

of the

1614 folio edition of Chapman’s translation with Clarke, searching for the some of the choicest passages; Clarke recollects their

overwhelming enthusiasm with Chapman’s work. The next morning, Clarke finds a letter

from

Keats on his table that contains a draft of Keats’s poetic response to his reading

of Chapman.

Keats’s sonnet of discovery captures a young poet’s keen desire for inspiration and

imaginative vision, though, in its fledgling enthusiasm, the poem also opens Keats

up to

certain class-based criticisms for not having the ability to read Homer in Greek. The poem is both certain and simple, and it expresses

Keats’s early desires to be an inspired and genuine poet, a subject that obsesses

(and

plagues) too much of his early poetry. The sonnet’s ending—envisioned as an explorer,

Cortez,

seeing with confused wonder from a peak

—peripherally recalls the tropes of an earlier

genre, the prospect poem, which is a variety of the topographical poem: the speaker

looks out

into the landscape from some position of height. If this kind of poem works well,

then some

insight is gained by looking out, which is consistent when Keats also compares himself

to an

astronomer discovering a new, unknown planet.* This insight Keats almost manages,

though in

this case it is a feeling that seems to confuse, or at best conflate, broader historical

circumstance with personal literary awe.

We have, then, the allegory of a poet looking and discovering, and he does so with some sense of profound uncertainty that is crossed over with wonder; this results in a feeling rather than in action; and that action will, Keats hopes, be the inspired production of an equal amount of awe for other viewers. That is, Keats in one sense hopes to become the seen more that the seer—the active, accomplished poet who is, so to speak, somewhere out there, over the horizon, rather than rather than the more passive, confused, and speculative gazer. Thus the uncertainty: What will the poet-traveller do with such serene, bold, and gilt-edged inspiration? More exploration is required. That Keats may have got the wrong explorer in the poem—mistaking Hernando Cortés for Vasco Nunez de Balboa (one Spanish conquistador for another)—makes little difference to the decent accomplishment the poem makes in the story of Keats’s poetic development. He seems geared up for further travels toward his goals.

So, here we find Keats, a poet in search of a subject of his own and in search of

an identity

and poetic character of his own. Like the astronomer he conjures in On First Looking into Chapman’s

Homer, he wonders about this new, undiscovered planet that he sees above him.

And like Cortez gazing out into a vast, unexpected and unexplored expanse, Keats is

not quite

sure, as a poet, what he now sees ahead of him. For Cortez, questions of eager uncertainty

(wild surmise

) cross the mind of Cortez and his followers. As mentioned above, it is

a form of Now what? or What next? Well, at least for the young poet who has

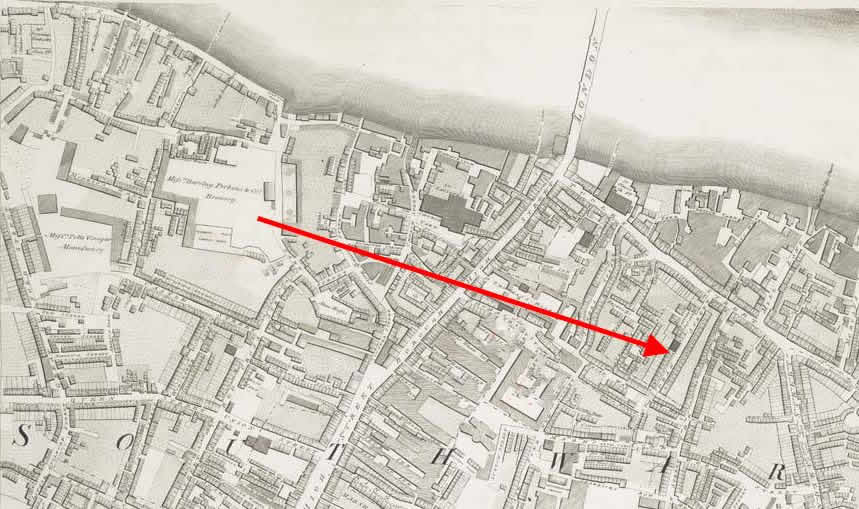

been spending his evenings at Hunt’s, they also picture a poet who has a good five

miles to

walk home—from Hampstead to Southwark—with the cold stars looking down upon him, which

is how

he describes himself in Keen, Fitful Gusts.

But more about that developing subject or pattern in On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer. As suggested, the poem intimates an uncertain future: Keats (as the awe-struck reader, the wondering astronomer, and the speechless explorer) stares out toward the unknown and the uncharted, toward, perhaps, some irresolute promise—searching-forward with unsettled knowledge. This, then, also allegorically acts out—dramatizes—a moment in Keats’s own poetic development, since, for Keats, the idea of looking forward to enduring poetic accomplishment seems, variously, and sometimes all at once, to inspire, plague, overwhelm, and confuse him. Keats at this point requires some acts of mediation—him to see Chapman, Chapman to see Homer, the astronomer to see a new planet, Cortez to see the Pacific—in order to understand not just greatness, but the idea of discovery itself. Thus, by the end of the 1816, in Sleep and Poetry, Keats will express that his poetic future depends upon having ten years to steep himself in how exactly to discover and then enact poetry; but he worries about failure, and he remains intimidated about how much toil and turmoil will come his way: as he puts it, “yet there ever rolls / A vast idea before me.” Thus in his late 1816 sonnet receiving a laurel from Hunt, Keats ends by thinking about “all the many glories that may be.” Yes—may be. And in another sonnet of this period (This pleasant tale, written February 1817), Keats recognizes that he never stops thirsting for “glory.” He needs to travel through realms of gold, but he also desires to create his own realm. Keats needs to become Keatsian.

Keats also composes a few further sonnets at this time—Keen, Fitful Gusts

and On Leaving

Some Friends—that reference his new friendship with Hunt and further reflect his desire for poetic inspiration. In the

first of the poems, he references the brimming friendliness of Hunt’s cottage (the

idea of

sociability cultivated by Hunt), as well as literary topics (like Milton and Petrarch)

discussed with Hunt and his new friends. As he writes in the second of these poems,

he hopes

for a golden pen

so that he can write down a line of glorious tone.

This is

touching and ambitious, given that Keats is, so to speak, a poetic newbie. But these

are

eager, overwritten verses—too many nouns demand an adjective—without much direction,

with

little specifics in larger aims, themes, or ideas. Perhaps most importantly, they

picture a

young, keen poet who finds himself within a that influential cultural circle—perhaps

the most

free-thinking and progressive of the Regency period. Lucky Keats.

An intimated future as a topic becomes more focussed moving into early 1818, when Keats in his poetry and poetics comes to fully confront and explore the expansive, enduring, and complex poetic accomplishment of, in particular, Milton and Shakespeare, specifically in light of his own poetic character and creative potential. In Lines on Seeing a Lock of Milton’s Hair (written 21 January 1818), futurity makes Keats desperate (burning, flushed, pained) to leave his undeveloped poetic self behind; but waiting years for some kind of poetic maturity is genuinely daunting. And then, the next day, in When I have fears, Keats worries that he may never be able to express what teems within him, that he will never (in his own term) ripen—though that ripening metaphor, taken over in 1819 and into the considerable poetic accomplishment of To Autumn, becomes the larger, deeper idea of quiet resolve and of gathering, sustainable potential. With the poem, we are offered the perspective of how he has traveled much beyond the anxious realms of future uncertainty.

So we can, this early, look forward: To Autumn and Keats’s poetry of 1819 thus answer his questions 1816 questions: How can I make this constant turn to the future less obstructive and more poetically productive? How can I, with some movement toward poetic profundity, address the doubt that accompanies this turn? How can uncertain promise lead to strong poetry? How do I write poetry of risk without it sounding risky? Again, the answers will develop, first, in his poetics toward the end of 1817, and then, by late 1818 and into 1819, in his poetry. We will see that it takes some work (call it study, maturity, development, experimentation, thinking) to cultivate these otherwise irritable reachings—these intimations of future doubts and uncertainties—as capable strengths rather than restricting weaknesses. This thinking will stand behind his most gainful subjects, and will be central to Keats’s narrative of extraordinary poetic development; and to watch Keats critically parse poetic quality in his letters (in, for example, his analysis of Shakespeare, Milton, Wordsworth, and imaginative knowledge) is indeed to witness the growth of Keats’s greatness.

With his brothers, in mid-November Keats moves from Dean Street to 76 Cheapside. Hunt will publish the On First Looking into Chapman’s

Homer in The Examiner at the beginning of

December, noting that the whole conclusion [of the poem] is equally powerful and quiet.

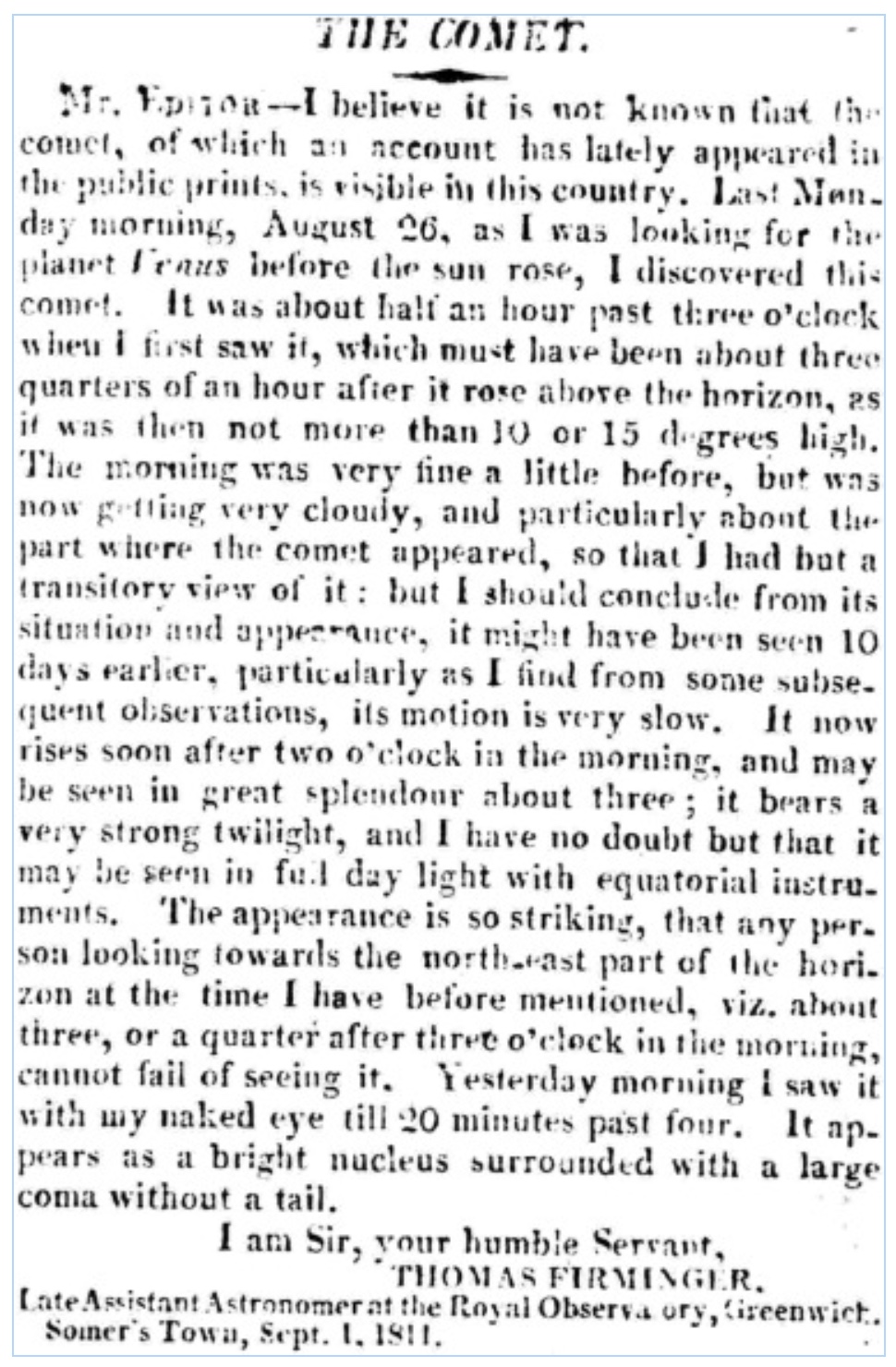

![Early draft (or more likely, fair copy) of On [the] first looking into

Chapman’s Homer (Houghton Library, Harvard University, Keats MS 2.4). Click

to expand. Early draft (or more likely, fair copy) of On [the] first looking into

Chapman’s Homer (Houghton Library, Harvard University, Keats MS 2.4). Click

to expand.](images/facsimiles/draftOfChapmansHomerHoughtonHarvardKeatsMS.jpg)