August 1814: Keats Visits the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens

Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, London

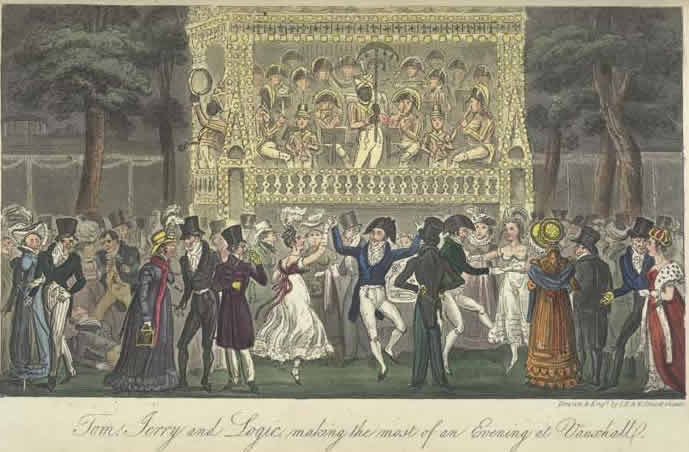

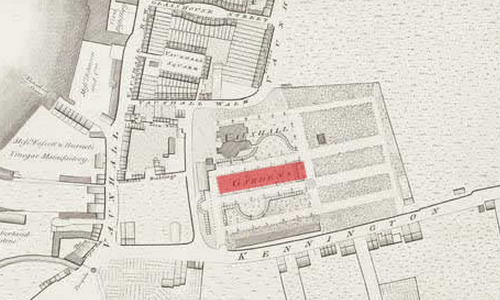

Keats goes to the extremely popular Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, a place that no doubt makes an impression on 18-year-old Keats, who in is the final year or so of being a medical apprentice, which he begins in 1811. [For more on Keats’s medical training, see 15 October 1815.] The gardens came into existence in 1770, and were sold to developers in 1859.

In Keats’s day, it was advertised as a place to which busy Londoners might retreat,

and in

particular, those of the so-called middling

classes. As the Morning Post of 8

August describes the Gardens, it is a place of splendid amusements.

Here the crowds,

all dressed up, gathered to view the novelties of fountains and fireworks, to watch

acrobatics

and to dance, to listen to both domestic and exotic music; to celebrate military achievement

and nationalism (keep in mind Britain is at war); to drink, mix, and take in the glitzy

vendors, the impressive decorations, and some of the commercial life of the times;

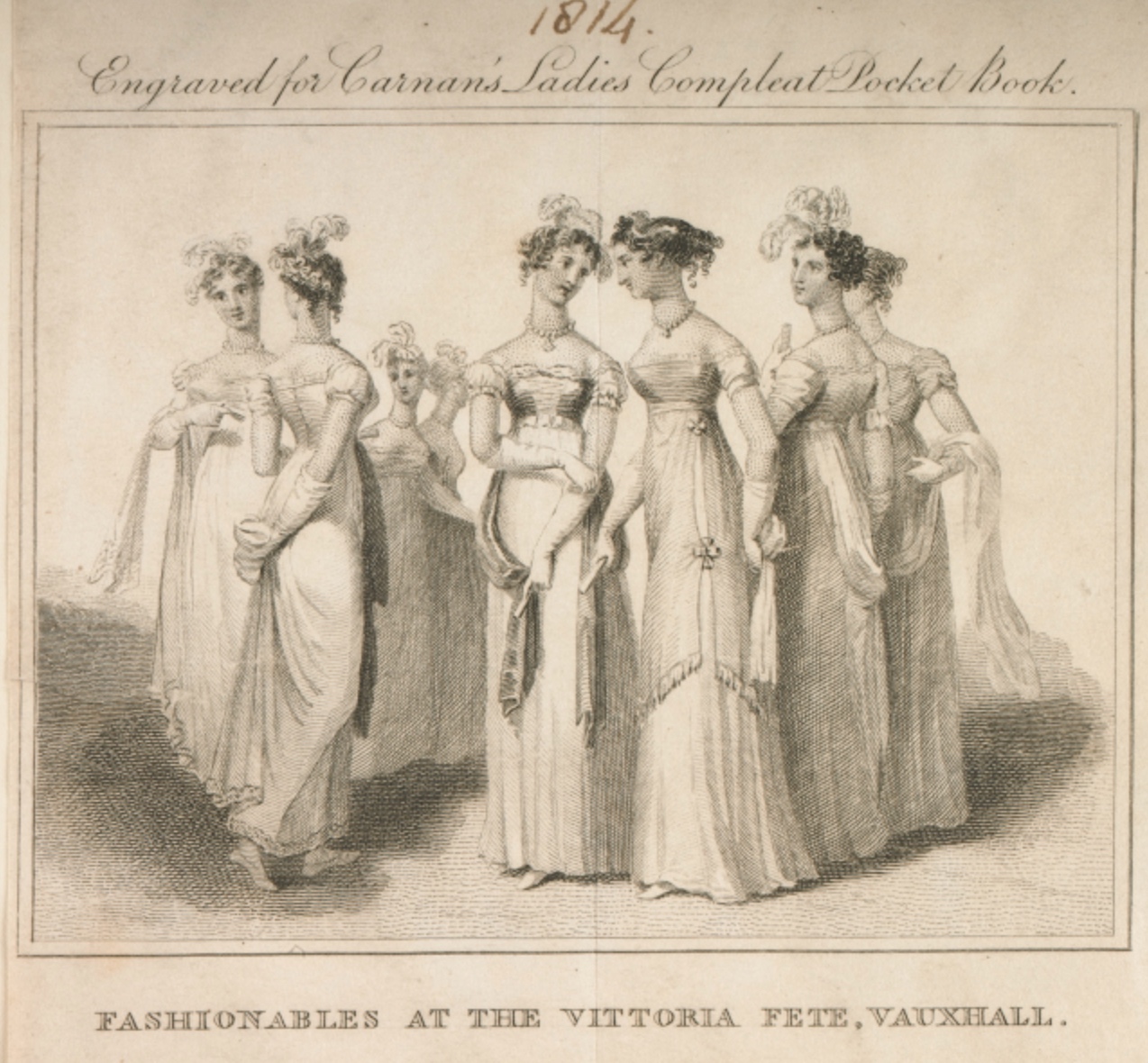

to parade

the latest fashions. There were even balloon flights. And of course there were more

transgressive behaviours both lurking and on show. In short, it was a place to see

and be seen

while promenading about the various pavillions, stalls, and sites—a place of what

we sometimes

call autovoyeurism.

And Keats does see: he gets a glimpse of a beautiful young woman, and she ends up

enduring in

Keats’s thoughts. In a resulting poem he writes soon after, he employs what today

we might

call a male gaze,

since in his fantasy he naively imagines her as both whore and ideal

woman, which in some ways is typical of Keats’s often conflicted picturing of women.

In the

poem (Fill for me

a brimming bowl), he claims he wants to avoid lewd desiring,

but, as he

notes, with his wandering thoughts this is in vain: he writes of her breast, earth’s only

paradise!

The poem’s description of her—The melting softness of that face — / The

beaminess of those bright eyes

—is, in its overly poeticized manner, not altogether

convincing or original, and the poem leaves us with his beating, smarting heart and

the

halo-covered, indelible memory of her. Angel or object of physical passion? Keats

will have to

work on this.

However, the woman must have made quite an impression! Keats returns to her in two

poems

written a few years later, and most strikingly in the February 1818 Shakespearean

sonnet Time’s sea has

been five years at its slow ebb. In his sweet remembering

of her, Keats

writes that he was fully captured: snared

and tangled

by her beauty—and, in

particular, by her ungloved hand, her eyes, her cheeks, and her lips. She’s the conflated

construction of imagination, memory, and desire; but the poem does not quite muster

the

complex play in Keats’s master model—Shakespeare’s love sonnets—where testing words

and

ingenious phrasing are often thrown our way to complicate both speaker and subject.

But it is

far better than his August 1814 effort, and demonstrates the direction of Keats’s

attempt at

mastery of form that will fully emerge in 1819.

1814, then, marks the year in which we have first evidence of Keats’s earliest poetic aspirations, though we know he wrote some verse before this year. What we have is not altogether memorable. It includes poetry to and about writers like Byron and Spenser, indicating he is, quite naturally, on the lookout for models and inspiration. Infatuation with Spenser’s imaginative world in The Faerie Queene particularly draws his interest (he reads much of it with Charles Cowden Clarke, the son of Keats’s former headmaster, and eight years older than Keats.) He also writes a confused but touching poem on the passing of his maternal grandmother, Alice Jennings (As from the darkening gloom a silver dove). She took loving care of him when his mother could not. Her death—after earlier deaths of his father (1804), grandfather (1805), and mother (1810)—represents the loss of his last strong connection with the elders of his family.

There is some suggestion that Keats perhaps begins his medical training (or at least some form of informal association with the London teaching hospitals) by mid-1814, though we do know that he formally registers at Guy’s hospital in October 1815 for a year-long course that would qualify him with the Royal College of Surgeons.