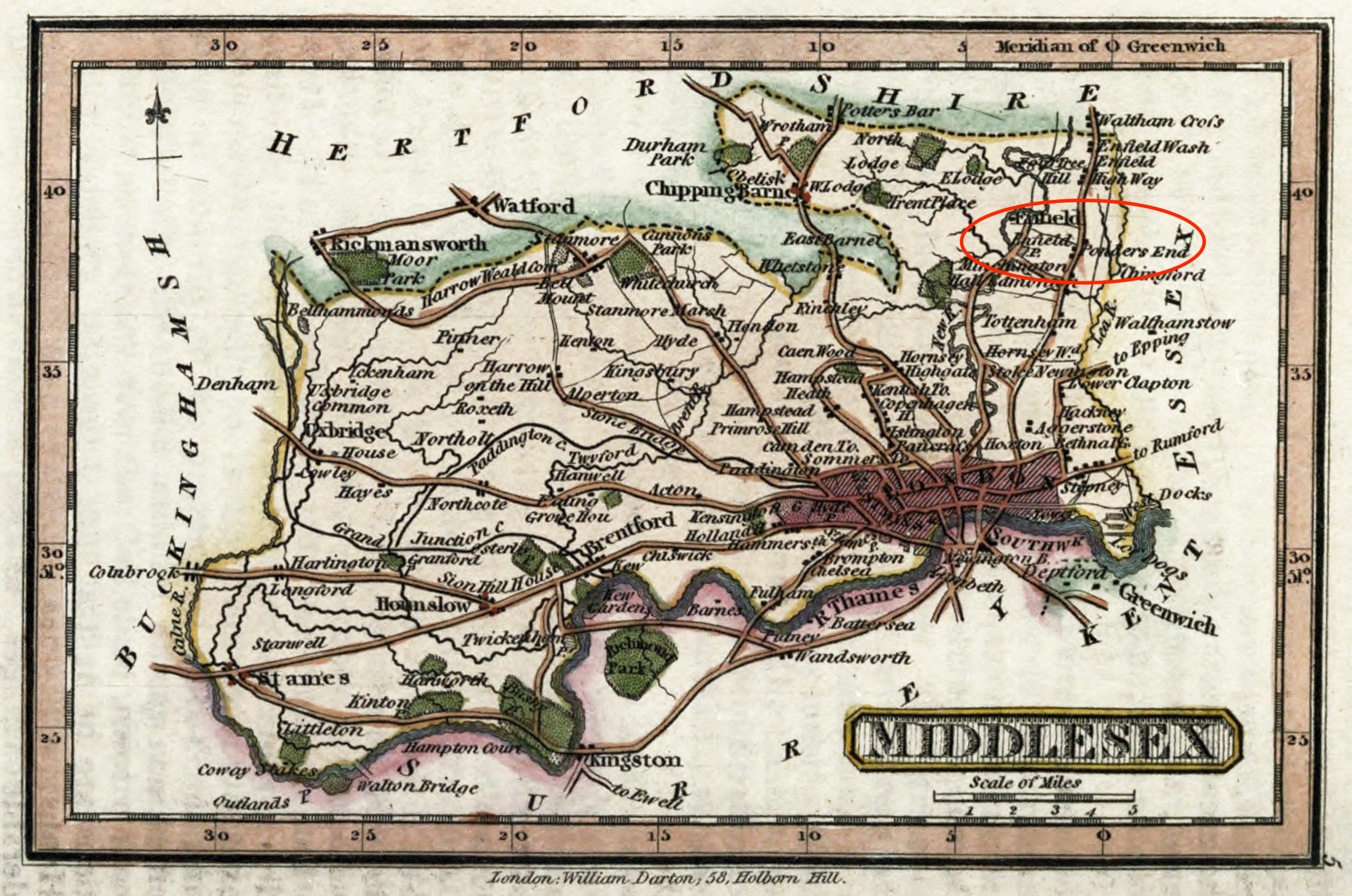

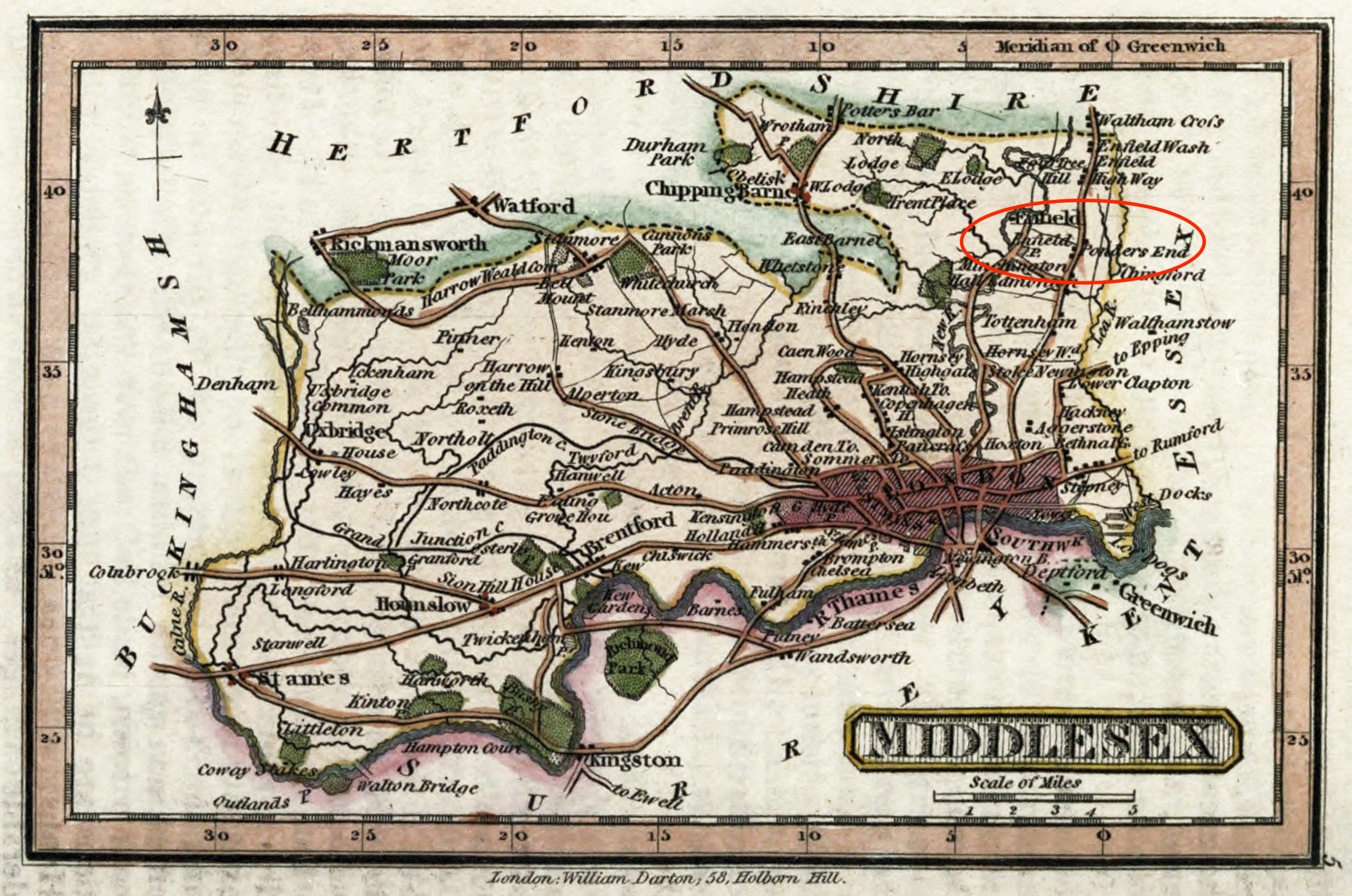

1803-1811: Clarke’s Academy in Enfield, Keats’s Education, & the Headmaster’s Son

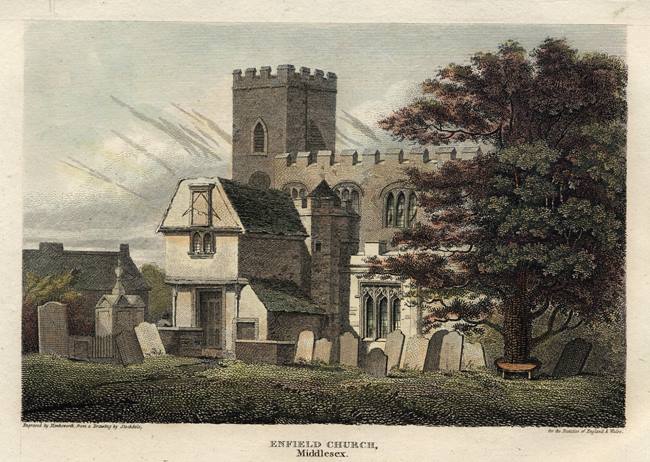

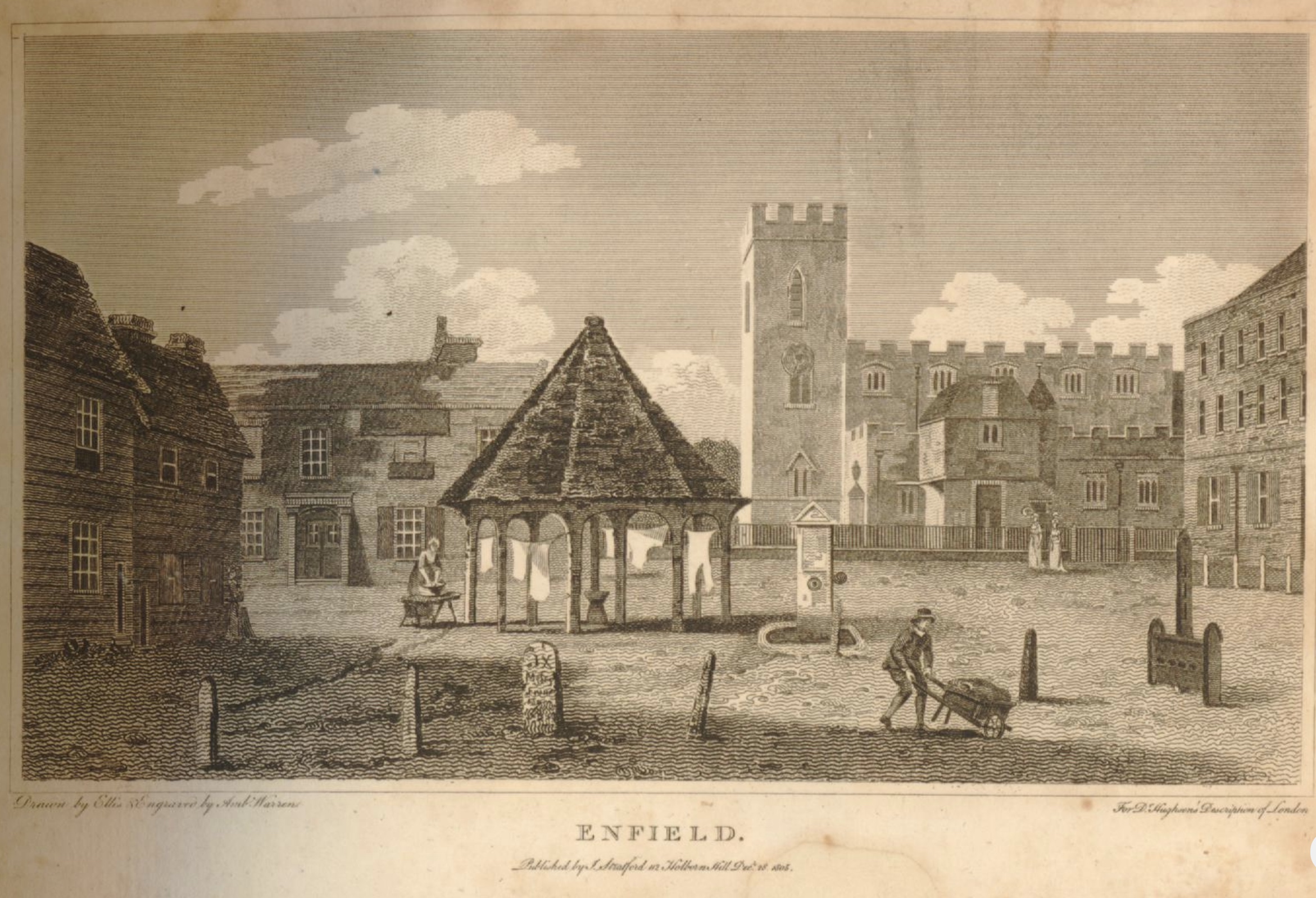

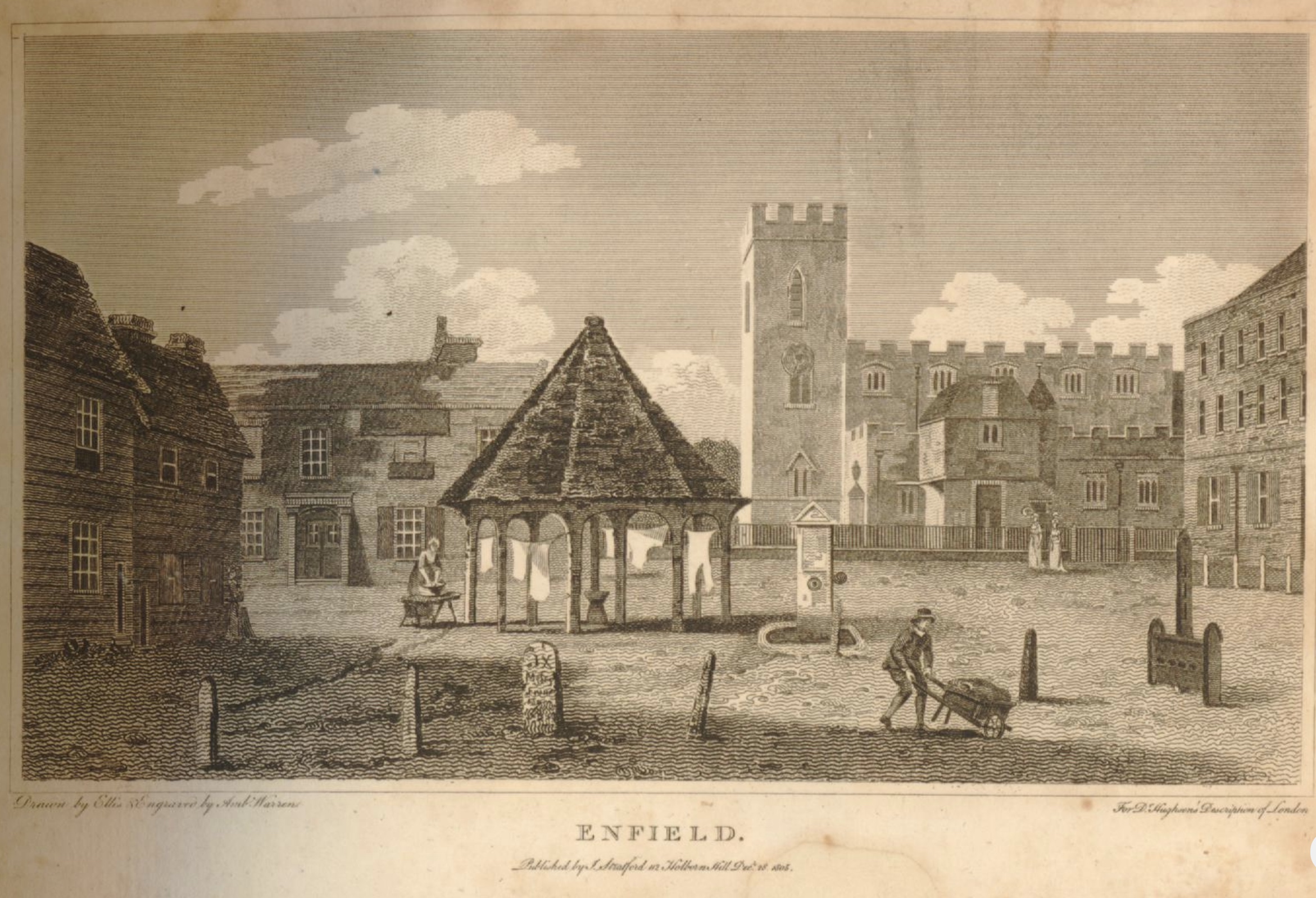

Enfield, Clarke’s Academy

Beginning August 1803, and with his younger brother George, Keats (aged 7) attends Reverend John Clarke’s boarding school for boys

(sometimes called Enfield School or Academy, and also known at the time as Mr. Clarke’s,

Enfield

). Keats’s youngest brother, Tom,

will later go to Enfield. In Keats’s time, somewhere between 70-80 students attend.

Clarke

retires as the principal of the school in 1810, close to when Keats leaves for a medical

apprenticeship.

The Keats brothers perhaps go to Clarke’s because of a little family history: a couple of their uncles on the mother’s side also go to the school, including the somewhat impressive Midgley John Jennings, a seasoned military (naval) man, who apparently sometime later occasionally dined with the Reverend Clarke at the academy.

Clarke’s Academy is significant inasmuch as it represents a continuous, predictable part of Keats’s life between 1803 and 1811, the period during which his father dies (1804), his mother hastily remarries (1804), he moves to live with maternal grandparents (1804), his maternal grandfather passes away (1805), and his mother dies (1810).

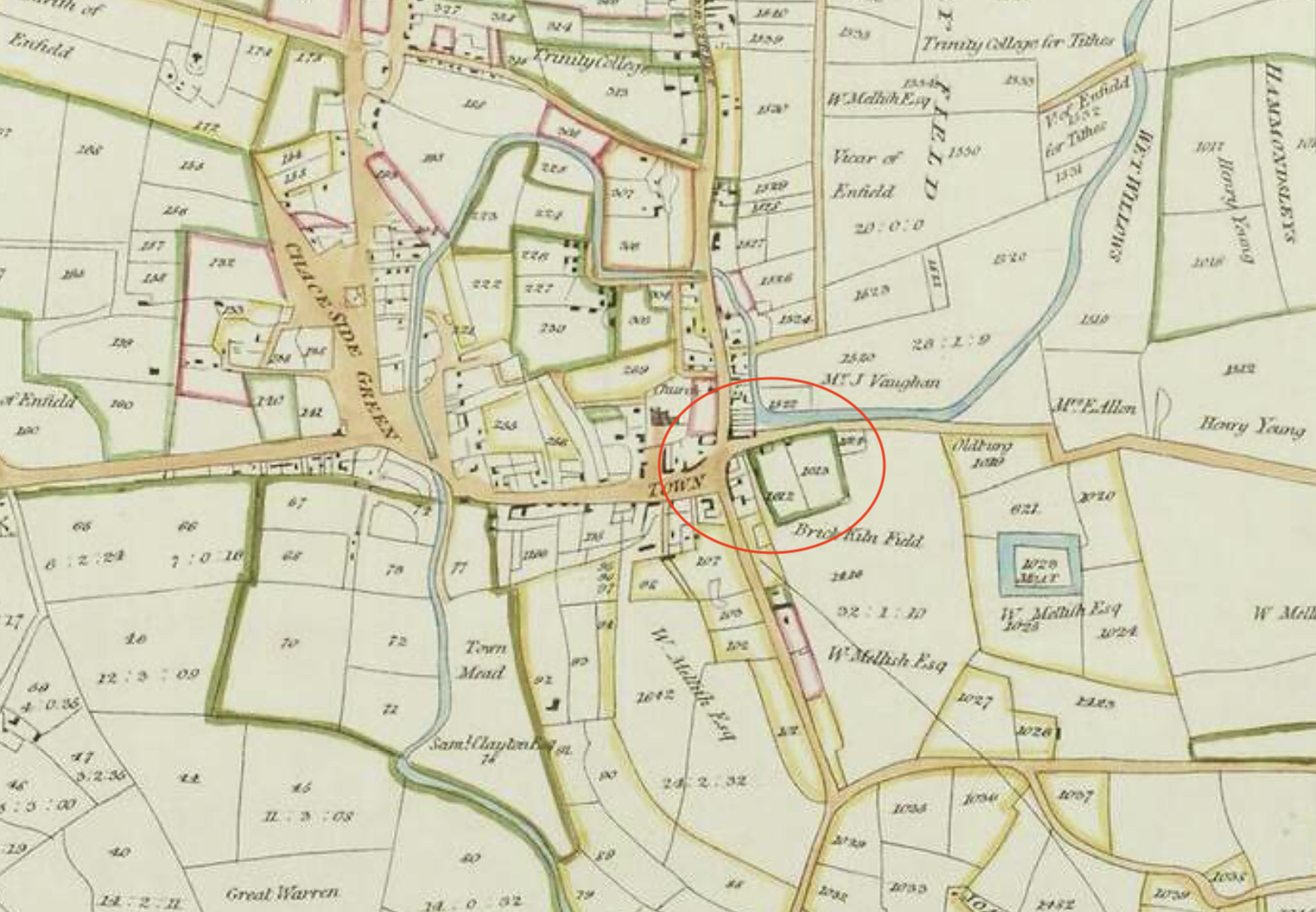

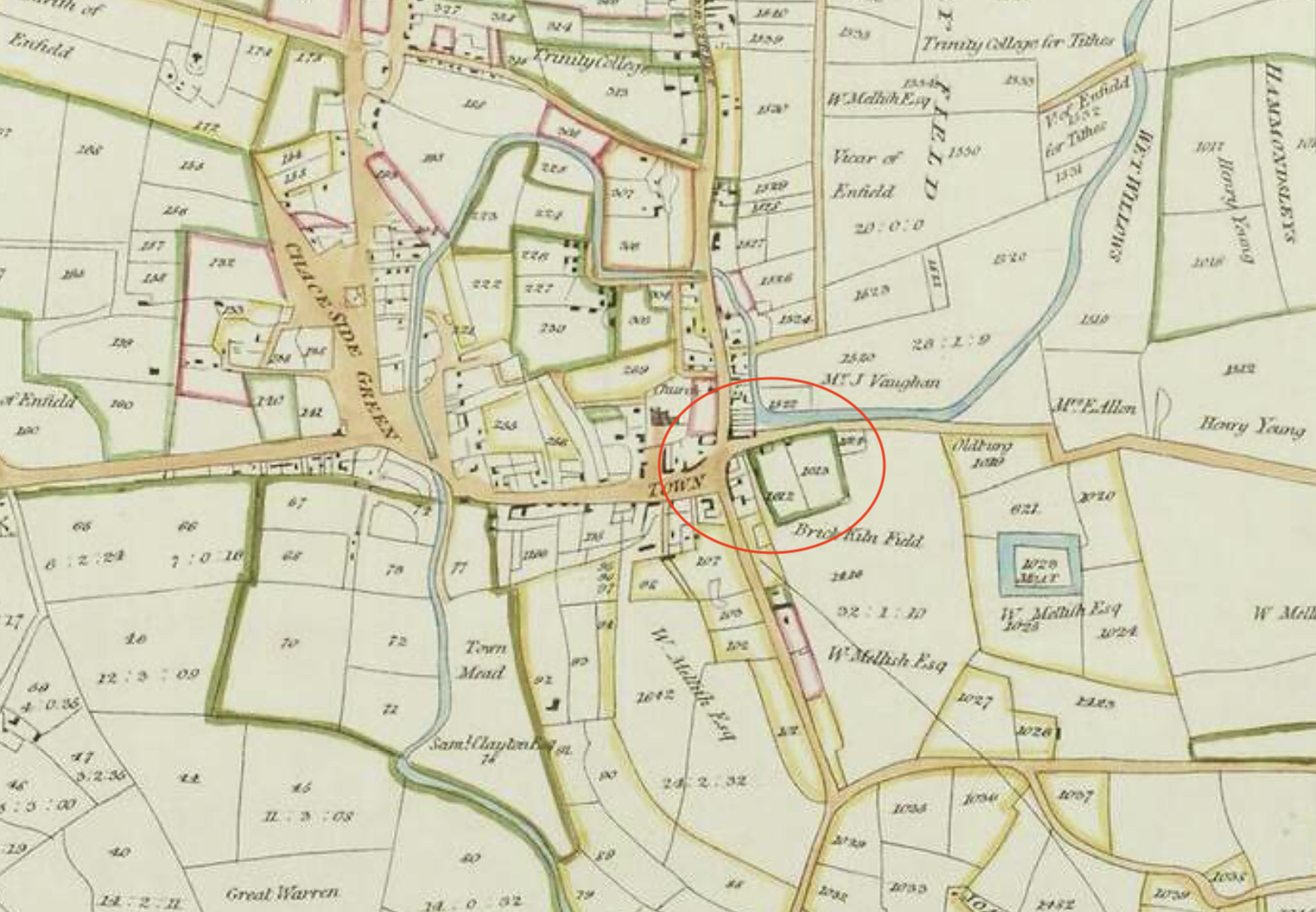

Physically, the school (on Nags Head Road, Enfield Town, about 10 miles north of London), with its large, airy rooms, is by no means gloomy. Outside there is a good-sized playground, as well as a large garden where some of the boys can cultivate their own little plot of land. Beyond the school grounds stretch some accessible meadows, though in adjacent areas there may have been some commercial development in the form of potash and brick manufacturing. The school is also quite close to Keats’s grandparents’ residence at Ponders End, where they retire in 1802. According to recollections of the headmaster’s son, Charles Cowden Clarke (who is eight years older than Keats), Keats’s parents—Thomas and Frances—were known to take their gig to visit the children at the academy; the unpretentious Keats family is apparently liked and respected by those running the school.

The school has a dissenting, nonconformist tradition. Clarke, upon the death of previous

headmaster, John Collett Ryland (1723-1792), strives through his pedagogy to background

knowledge with faith, but always in the spirit of genuine curiosity, experience, and

discovery. Clarke inherits much of his educational philolsophy and approach from Ryland.

As

Ryland articulates in his innovative 1792 A Plan of Education,

besides scriptural

knowledge, the Ingenuous Youth of Great-Britain

should be exposed to a wide range of

subjects, both academic and practical, as well as being fully conversant with all

branches of

science. Ryland was especially keen on math, geographical facts, and astronomy; he

developed

fully innovative pedagogical methods, such as learning card games, based on (as he

let it be

known) his near Fifty Years

of teaching. (Today, we might call some of Ryland’s

approach active learning.

) As Clarke succeeds Ryland, and on the more ideological side,

no doubt some republican (and therefore radical) sympathies filter through the school’s

students; this would have been touchy stance given Britain’s ongoing war with France,

which is

more or less continuous, 1793-1815.

Correspondent with those republican sympathies, it noteworthy that the school also takes copies of Leigh Hunt’s Examiner, an independent, progressive, and often controversial newspaper, with Hunt being something of a celebrity journalist for his outspoken views, and for being jailed for sedition in 1813 (he was famously imprisoned for two years). In fact, the newspaper will be formative in Keats’s career in ways that Keats, as a schoolboy, could hardly have imagined: his first published poem—O Solitude—will be in The Examiner (5 May 1816). How did this happen? It is Charles Cowden Clarke, in fact, who eventually tells Hunt about Keats, and then he introduces young, unknown Keats to Hunt in October 1816; but Keats likely took it upon himself to send his sonnet to Hunt, prior to having any direct connection with Hunt. Crucially, meeting Hunt via Clarke immediately connects Keats with an important faction of London’s literary network of publishers, journalists, publishers, poets, artists, and writers, and this changes everything for him. The meeting solidifies Keats’s determination to become a poet.

[This graph of Keats’s social network shows the importance of Clarke and Hunt as hubs.]

The school greatly encourages its students to pursue all forms of knowledge and, at times, to set their own consequences for negative behaviors or indifferent commitment. The boys are fully encouraged to take responsibility for what they learn—merit is given for volunteered and independent learning. There is no fagging at Clarke’s, though it was an accepted practice at the more elite British public schools.

The sustaining idea at Clarke’s school is to produce self-motivated freethinkers; the pedagogical style is to reward rather than to punish. That some of Keats’s poetry comes to challenge accepted conservative tastes, and that he develops an independent voice, is not surprising; likewise, that Keats develops highly independent religious views is hardly surprising.

Keats, then, receives a very good, if not exceptional, education at the academy. He

gets his

French, Latin, and core subjects, but also exposure to science and to widening subjects

ranging from optics to gardening. Moreover, after a somewhat undirected beginning

at the

school, when undersized, feisty Keats is more than willing to take on the bullies,

Keats

eventually becomes known for his stamina as a reader and for after-hours study. According

to

Charles Cowden Clarke, it seems Keats reads

most, if not all, of the books in the library, and he often reads during meals; Clarke

recalls

Keats’s reading habits: he devoured rather than read.

It seems he is especially taken

with Greek mythology.

Much of this becomes extraordinarily significant in the narrative of Keats’s poetic

progress,

where he often makes it clear that he needs—on his own terms, on his own time—to deliberately

study poetry in order to achieve his emerging, genuinely lofty ambitions. Keats recognizes

that such progress will require work, what he will call the drinking in of Knowledge,

which can only be gained through application study and thought

(letters, 24 April

1818). His goal, as he later writes just before his 23rd birthday: to be among the English

Poets after my death

(letters, 14-25 Oct. 1818).

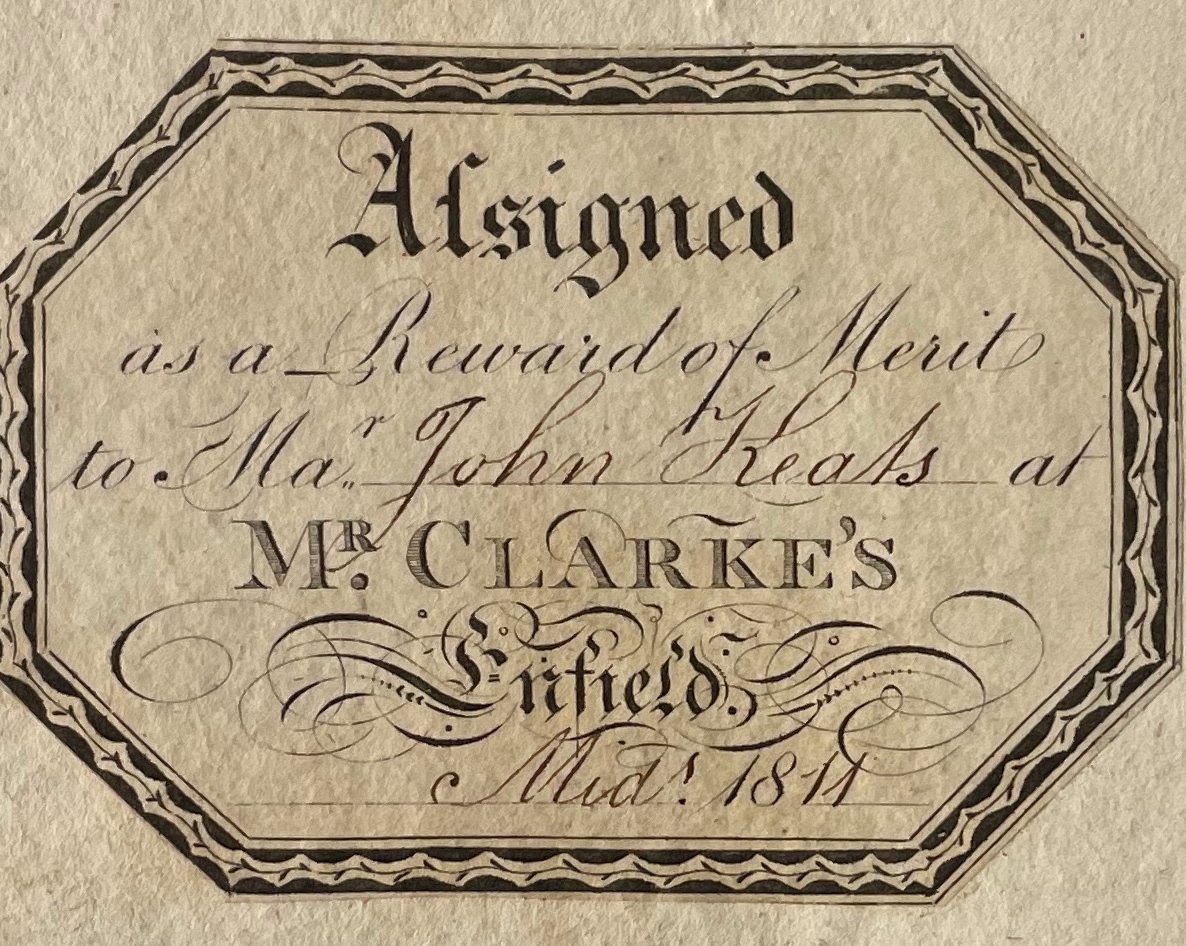

In his final terms at school, Keats is formally rewarded for his hard work, winning

merit

prizes in the form of books: in 1909, C. H. Kauffman’s 1803 Dictionary of Merchandize and

Nomenclature in All Language; and in 1811 he is awarded a copy John Bonnycastle’s 1807

An Introduction to Astronomy. Further, in 1810, he receives a silver PRIZE

MEDAL

that acknowledges his diligent scholarship; and in 1812, after he leaves the

Academy, he receives what seems to be a further book prize (noting his emeritus status),

in a

copy of an 1806 Latin edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoseon.

![Bookplate: 1811 Reward of Merit to Ma [Master] John Keats in

Bonnycastle’s An Introduction to Astronomy. My thanks to the Huntington Library’s

rare book collection for this image. Click to enlarge. Bookplate: 1811 Reward of Merit to Ma [Master] John Keats in

Bonnycastle’s An Introduction to Astronomy. My thanks to the Huntington Library’s

rare book collection for this image. Click to enlarge.](images/keatsBookplateAward.jpg)

Reward of Merit to Ma [Master] John Keatsin Bonnycastle’s An Introduction to Astronomy. My thanks to the Huntington Library’s rare book collection for this image. Click to enlarge.

A side narrative: While Keats moves through the academy, Cowden Clarke had begun to encourage and direct Keats’s early poetic tastes; now, as Keats concludes these final terms, this continues, and they are close friends up until 1817.

Keats will recognize Clarke’s encouragement in the September 1816 epistle To Charles Cowden

Clarke. The poem stumbles around Keats’s somewhat immature desires to be an

enduring poet, but it genuinely thanks Clarke for first teaching him all the sweets of

song

(53). At this point, these aspirations falter between insecurity and a little

pretentiousness, which, given Keats’s age and experience, is to be expected: that

is, Keats is

nowhere close to finding anything like a relatively mature poetic voice or coming

up with

inventive subjects—he has not yet evolved a poetic persona less concerned with fame

and poetic

affectation and more concerned with capturing something universally deep, clear, and

original.

After leaving school, while he begins medical training, Keats’s school-based task to complete translating Virgil’s epic, The Aeneid, continues. With the project, Keats doesn’t show his continuing interest in literary scholarship, but in the process he apparently evaluatively assesses the classical work, thus pointing to Keats’s early critical acumen: Cowden Clarke recalls that Keats, barely a teenager, actually finds flaws in Virgil’s narrative structure!

Bottom line: the style and regiment of Clarke’s Academy, Cowden Clarke’s interest in tutoring Keats even after leaving the Academy, along with him engineering Keats’s meeting with Leigh Hunt, are key in setting Keats’s direction as a poet, and so the narrative of Keats’s poetic progress has clear origins at Enfield.

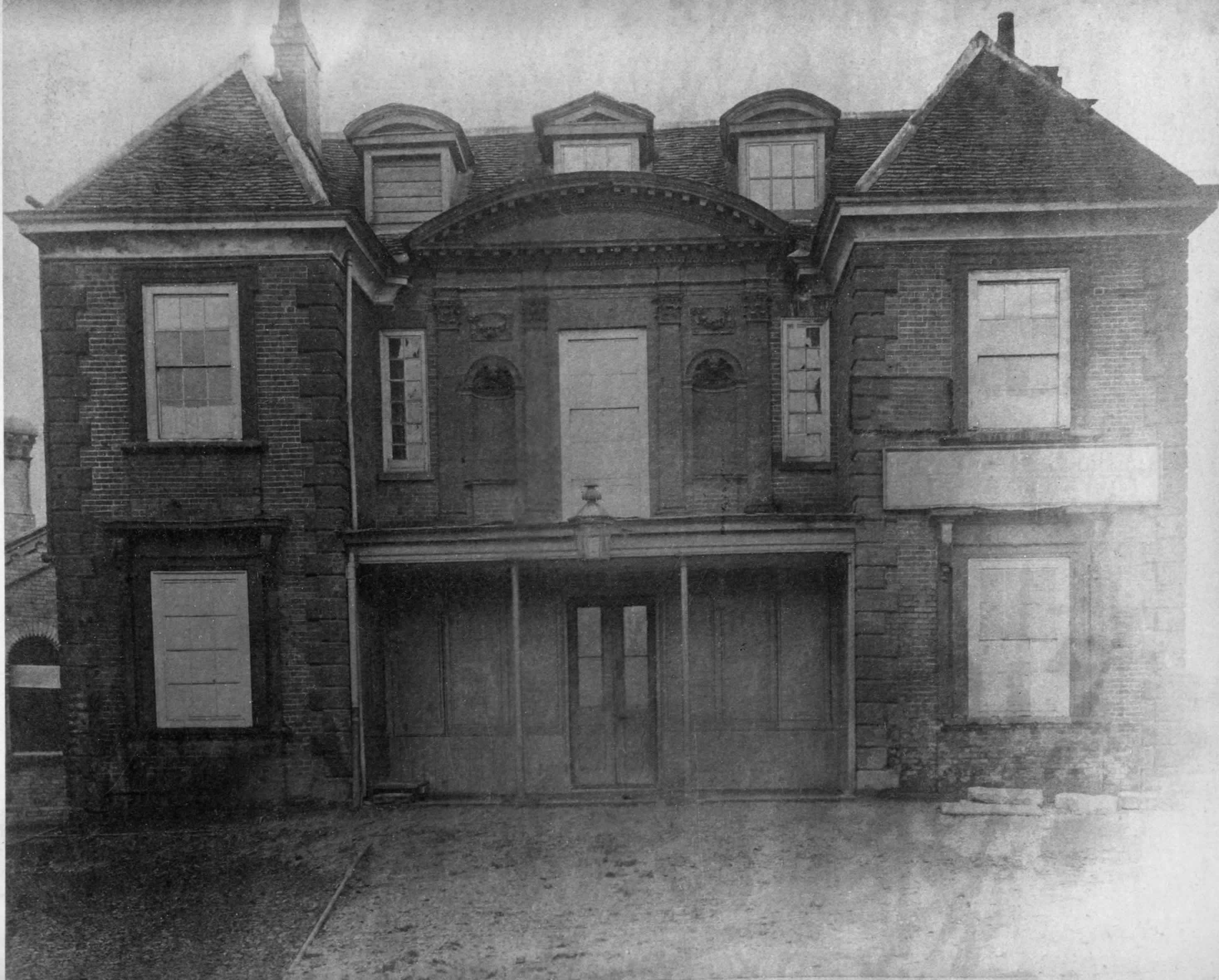

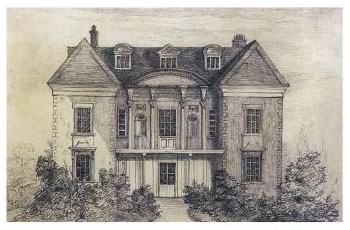

*My sincere thanks to Leonard Will and Dave Cockle of the Enfield Society for images

and

information about the school and its location. Something about the building: According

to the

Victoria & Albert Museum, the frontage of the school-house was based on designs by

Sir

Christopher Wren (1632-1723): The station was demolished in 1872; the façade however was

saved, and originally purchased for the Structural Collection of the Science Museum,

then

part of the South Kensington Museum […] The acquisition of the façade is recorded

in a

contemporary publication about Enfield by Edward Ford. He noted: …it was taken down

brick by

brick, with the greatest care, all being numbered and packed in boxes of sawdust for

carriage. Nothing could exceed the beauty of the workmanship, the bricks having been

ground

down to a perfect face, and joined with bee-wax and rosin, nor mortar or lime being

used. In

this manner the whole front has been first built in a solid block, the circular-headed

niches, with their carved cherubs and festoons of fruit and foliage, being afterwards

cut

out with the chisel.

The building also came to be known as THE OLD HOUSE.